This is Mary Harrington. She has written a book, and here it is:

Mary is an academic. She describes herself as someone who has “liberalled as hard as it is possible to liberal.” She believed all the lies that were told her by the sexual revolution, and though she has no desire to share the details, says her experience of it was comparable to that of Bridget Phetasy, with her famously heartbreaking article, “I Regret Being A Slut.”

Progressivism is no longer in the interests of women

As you can see from the phrase that makes “liberal” into a verb, Mary has quite the way with words. The basic thesis of her book is that the progressive religion, by making personal autonomy the only definition of the good to which everything else must be sacrificed, has gone way past the point of diminishing returns and is now actually harming women rather than helping them. But since Mary is so articulate and fiery, she can put it far better than I can:

We’re increasingly uncertain about what it means to be [sexually] dimorphic. But when we socialise in disembodied ways online, even as biotech promises total mastery of the bodies we’re trying to leave behind, these efforts to abolish sex dimorphism in the name of ‘human’ will end up abolishing what makes us human men and women, leaving something profoundly post-human in its place. In this vision, our bodies cease to be interdependent, sexed and sentient, and are instead re-imagined as a kind of Meat Lego, built of parts that can be reassembled at will. And this vision in turn legitimises a view of men and women alike as raw resource for commodification, by a market that wears women’s political interests as a skin suit but is ever more inimical to those interests in practice.

What we call ‘feminism’ today … should more accurately be called ‘bio-libertarianism,’ [and it is] taking on increasingly pseudo-religious overtones. This doctrine focuses on extending individual freedom as far as possible, into the realm of the body, stripped alike of physical, cultural or reproductive dimorphism in favour of a self-created ‘human’ autonomy. This protean condition is ostensibly in the name of progress. But its realisation is radically at odds with the political interests of all but the wealthiest women — and especially those women who are mothers.

… nothwithstanding the hopes of ‘radical’ progressives and cyborg feminism, a howlingly dystopian scenario can’t in fact be transformed into a dream future just by looking at it differently.

ibid, p. 17, 18, 19

I mean, I couldn’t agree more. The most obvious people to suffer from the real-life application of what Mary elsewhere calls “Meat-Lego Gnosticism,” are children. Babies and children need their moms. In fact, Mary’s thinking began to really change on this topic of progress when she had a child of her own and was shocked by the instant bond.

But even a little bit of thought shows that women are also suffering, because most women, like Mary, actually want to bear and raise their own children, preferably in a household with the child’s father. And, in fact, men are suffering too, not only because half of those motherless children grow up to be men, but because it turns out that humans were made to be embodied, and so living a disembodied life, alienated from our physicality and from human relationships, makes all humans miserable.

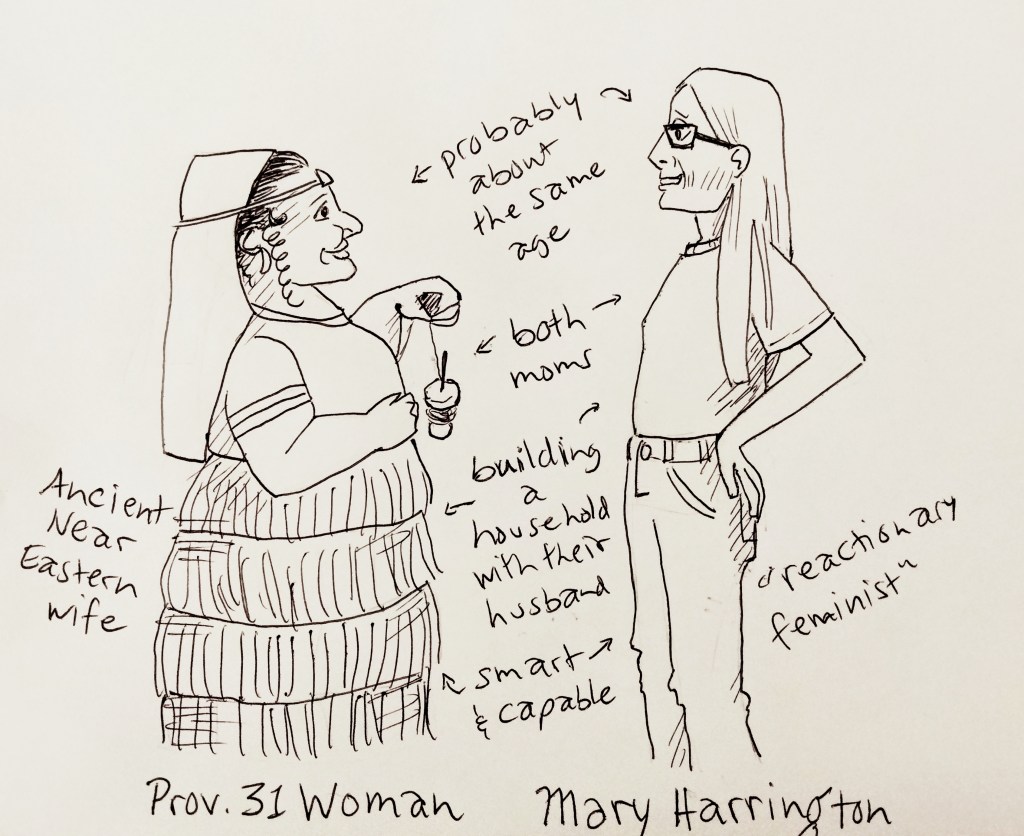

Mary calls herself a “reactionary feminist” because she is reacting against “progress” in favor of the interests of women.

Down with Big Romance

Often, when people reject progressive feminism, the only alternative that they hear presented is “traditional marriage,” by which they mean the 1950s sitcom model. But that model is actually not traditional marriage so much as postindustrial marriage.

Harrington spends a lot of space in the book pointing out how, with industrialization, many of the homesteading tasks that were once the responsibility of the housewife got outsourced to the market. She draws on Dorothy Sayers for this, who pointed it out a long time ago in her essay “Are Women Human?” I wanted to quote Sayers directly, but don’t have a copy of the essay on hand. Essentially, she says that before the industrial revolution, women got to do milking, cheesemaking, beer brewing, baking, spinning, weaving, sewing, mending, and a number of other arts and crafts that took quite a lot of skill and are also fun. Sayers’ main point is that, in the wake of all these trades being moved out of the household, it is no wonder that middle- and upper-class women are bored and would like to do something other than sit around the house. Harrington’s application of this point is a little different. She points out that in economic terms, before industrialization a wife contributed really essential labor to the household. A husband could not get along economically without her. Because both spouses were committed to keeping the same ship afloat, the man was less likely to abandon the woman.

Post- Industrial Revolution, the woman (particularly in upper and middle classes) now contributed much less to the household economically. The man was the sole wage earner, which gave him a lot of economic power. He could treat his wife badly, and she’d have no recourse. It is to this shifting dynamic that Harrington attributes the rise of Big Romance. A husband and wife must like each other, must be madly in love, and then he will treat her kindly despite the imbalance of economic power.

I think Harrington’s analysis has merit, though it doesn’t tell the whole story. For example, I would argue that relations between men and women first got badly messed up at the Fall. Wife abuse was certainly possible before the Industrial Revolution. Also, I would argue that Big Romance owes something to the concept of Courtly Love in the Middle Ages, which in turn owes something to Paul’s exhortation to newly Christianized former pagans: “Husbands, love your wives as Christ loved the church and gave Himself up for her.” But all that said, I do think Harrington is on to something here. Obviously, when we are talking in broad strokes about the relationships between men in general and women in general, over centuries or millennia, there are going to be a ton of cultural and historical and literary and religious and yes, economic factors that go into it, even if we confine our survey to just the West.

Mixed-Economy Households

So, if we don’t like Meat-Lego “feminism” and we don’t like 1950s Big Romance, what’s left? At this point, Mary’s book begins to have the feel of re-inventing the wheel. Metaphors abound that compare modern men and women’s situation to rebuilding, using broken tools, in a postapocalyptic wasteland. Mary doesn’t know a lot about what a life that is good for women, children, and men should look like, but she is pretty sure that for the majority of people, it’s going to be in families built on heterosexual marriage. And she’s aware that, to find a good model, we’ll have to go back before the Industrial Revolution.

Here’s what she comes up with.

The weakness of [proposals to go back to 1950s style marriage] isn’t that they’re unworkable, or even that they’re ‘traditional,’ but that they’re not traditional enough. For most of history, men and women worked together, in a productive household, and this is the model reactionary feminism should aim to retrieve.

Remote work, e-commerce and the ‘portfolio career’ are not without risks … But cyborg developments also offer scope for families to carve out lives where both partners blend family obligations, public-facing economic activity and rewarding local community activities in productive mixed-economy households, where both partners are partly or wholly home-based and work collaboratively on the common tasks of the household, whether money-earning, food production, childcare or housekeeping.

ibid, p. 179, 180

She then profiles two young women who are doing just that. Willow, in Canada, is a writer and mom to a small baby who, when childcare allows, also works with her husband on the family woodworking business. (He does the building, she does the finishing, basically.) Ashley and her husband, in Uruguay, have three children and do a mix of homesteading and language teaching.

In [Ashley’s] view, the romance comes not through the ego-fulfillment of a perfectly congenial partner, but working with someone to build something that will outlast them: ‘It’s much more romantic in the end when you realise this home, this life, these children, if they’re thriving it’s a result of our shared ability to create something greater together through our interdependence and cooperation … We’re working towards something bigger than ourselves. We’re building a legacy.’

Isn’t this a rather bleak and utilitarian view of a long-term relationship, though? To this I can only say that in my own experience, in practice the Big Romance focus on maximum emotional intensity and minimum commitment is bleaker. … A commons is, by definition, not available for consumption by anyone with the freedom to contract, or the money to buy, but only to those who share and sustain it.

ibid, pp. 183 – 184

What’s interesting about this vision of the household is that it has been described, not by “conservatives,” but by Reformed Christians, frequently, even within the past few years. Douglas Wilson, whom Mary Harrington has perhaps never heard of, has by now written a small library’s worth of volumes on this very topic. His daughter, Rebekah Merkle, has a book and a documentary about it, both called Eve in Exile.

And here, in his video Theology of the Household, Alistair Roberts lays out a view that is strikingly similar to the one in Harrington’s book:

Not surprisingly, these Christian thinkers are getting their picture of a household that is good for both men and women from … the Bible. And now I’d like you to meet Reactionary Feminism’s poster girl, and surprise! it’s not Mary Harrington.

The Proverbs 31 Woman

A wife of noble character who can find? She is worth far more than rubies. Her husband has full confidence in her and lacks nothing of value. She brings him good, not harm, all the days of her life. She selects wool and flax and works with eager hands. She is like the merchant ships, bringing her food from afar. She gets up while it is still dark; she provides food for her family and portions for her servant girls. She considers a field and buys it; out of her earnings she plants a vineyard. She sets about her work vigorously; her arms are strong for her tasks. She sees that her trading is profitable, and her lamp does not go out at night. In her hand she holds the distaff and grasps the spindle with her fingers. She opens her arms to the poor and extends her hands to the needy. When it snows, she has no fear for her household, for all of them are clothed in scarlet. She makes coverings for her bed; she is clothed in fine linen and purple. Her husband is respected at the city gate, where he takes his seat among the elders of the land. She makes linen garments and sells them, and supplies the merchants with sashes. She is clothed with strength and dignity; she can laugh at the days to come. She speaks with wisdom, and faithful instruction is on her tongue. She watches over the affairs of her household and does not eat the bread of idleness. Her children arise and call her blessed; her husband also, and he praises her: ‘Many women do noble things, but you surpass them all.’ Charm is deceptive, and beauty is fleeting, but a woman who fears the Lord is to be praised. Give her the reward she has earned, and let her works bring her praise at the city gate.

Proverbs 31:10 – 31, NIV

Wow!

So, this is an older lady, a matriarch. She has children, and she is honored both by her husband, her children, and the public for her role as a matriarch. (Contrast this with Meat Lego feminism, where being a mom means you are dumb and irrelevant.) Perhaps this lady is beautiful, but we are not told that. In any case, she is an older woman, and “beauty is fleeting.” Her beauty has faded. But she has style (clothed in linen, purple, and scarlet). There is a lot of emphasis on her strength and capability. She engages in cottage industry, she has employees (servant girls), and she handles money and gets into real estate. She speaks with wisdom and faithful instruction, which probably primarily is directed at her children, but this could include her mentoring younger women and nowadays it could include being a writer like Willow. Her husband is a pillar of the community, and this is not to the exclusion of his excellent wife, but because of her and because of the kind of household they have built together. She, too, is known in the community and opens her hands to the poor. They are the people you go to if you need advice or help.

And, finally, this lady is not meant to be an outlier. “Many women do noble things, but you surpass them all.” The idea is that there are a lot of amazing women out there, but every husband should feel this way about his wife, that she is the best. The Prov. 31 woman is an older matriarch, so she has had time to build up an impressive portfolio of skills and accomplishments that for many young moms is years away. But this is where they can end up, if they are given support and honor in their role as moms and are shown what is possible.

In other words – I wouldn’t make this a headline without context as it would be misunderstood, but — the Prov. 31 Woman is the original Girl Boss.

Pingback: A Gnome Love Story – Out of Babel

Pingback: Send in the Crones – Out of Babel Books