Well, it’s that time of year again: the long, long weeks of post-Christmas winter, when we grit our teeth and read the books that are not fun but are good for us. I think it was this time of year, a few years ago, that I read The Gulag Archipelago by Aleksandr Solzehenitsyn. This is similar.

The poison of class war

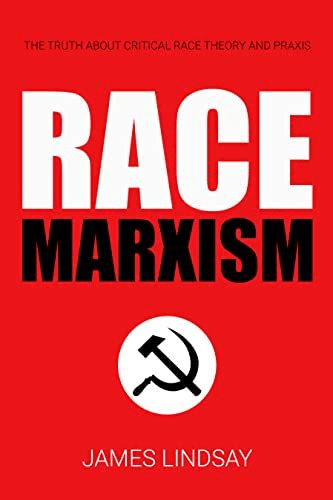

First, some background. I don’t like Marxism. I don’t like anything that has even the faintest hint of class war in it, in fact.

I was a sensitive, easily guilt-tripped child, and I grew up in a “Christian” denomination that had an intermediate-to-advanced case of marxist infection in its Sunday School materials. They would take verses like “blessed are the poor” and “how hard it is for the rich to enter the kingdom of God!” and use them to make it clear to me that being an American, with a high standard of living relative to the rest of the world, was not only a sin, but a very special sin, in a category all its own, because this was one sin which you could not repent of and to which the blood of Jesus did not apply. I was the “evil rich,” and there was nothing I could do about it. Also, because of this, I was morally guilty for any suffering that happened anywhere in the world, provided that the United States was somehow involved or the people suffering were “poorer” than I was. And I swallowed all this. I felt guilty, not grateful, for every little purchase or luxury. And eventually, I felt defensive about them.

I now know, based upon what I have learned since, that marxian systems by their nature do not include repentance or grace. These are Christian concepts. We cannot expect them from a system that works by designating a villain class, then constantly expanding that class. I had already figured out, simply from applying common sense, that the “logic” of class-war thinking is illogical, years before Lindsay came on the scene, but once I started reading him, it became even clearer.

As a simple piece of first advice for pushing back against Critical Race Theory, stop assuming it has good intentions. Individual people pushing Critical Race Theory might have good intentions, but the Theory they are applying does not. For liberals, this is a tough pill to swallow. Critical Race Theory ideas are not liberal ideas, and they cannot be considered on liberal terms. They are viruses meant to infect the liberal order. Assuming the ideas must mean something more reasonable than it seems or that activists won’t equivocate between meanings in a strategic way to seize power will cause you to lose every single time.

ibid, pp. 254 – 255, emphasis in original

There is no redemption in a marxian system. The only way you, as a dirty resource hog, could possibly redeem yourself would be to fix all the problems and all the suffering in the world. Since you can’t do that, you will probably die in the Revolution. Sorry not sorry. And you’ll deserve it.

It still baffles me when well-meaning people (usually women, TBH) try to “comfort” me by telling me something along the lines of “It’s not your fault. It’s the fault of Capitalism. You are the oppressed. The System needs to change.” (“It” could be anything from the difficulty of navigating the health insurance system, to eating healthy.) I just want to shake their shoulders and say, “Are you kidding? We are the ‘capitalists.’ We are the ones they hate and blame. If you blame ‘capitalism,’ you are blaming me and saying I should not have any private property.”

This sounds kind of self-pitying, so let me hasten to add that I fully realize that being guilt-tripped, blamed, and messed up in the head over your class status is by far the least harmful outcome for anyone exposed to Marxist ideas. For millions of people who were more directly affected, it cost them their very lives. However, my little story does illustrate how the only fruit of class-war rhetoric is to divide people from one another and give them hang-ups. It never makes relationships better.

O.K., so that’s bit of background #1. Me and Marx – not good buddies. No, indeed.

A challenging book to read

Second bit of background: over the past several years, I have listened to many, many hours of lectures by James Lindsay. It was a fellow Daily Wire reader who first pointed me to Lindsay’s website, New Discourses. (Fun fact: one of my kids for several years thought the site was called Nudist Courses.) Anyway, Lindsay’s podcasts quickly became a regular feature of my listening-during-chores lineup. I would do dishes, pick berries, paint, or fold laundry while listening to his dry, mathematician’s voice punctuated by occasional naughty words when the stupidity of the ideas he was describing provoked him really, really bad.

I listened to Lindsay talk about the Grievance Studies Project that he carried off with Peter Boghossian and Helen Pluckrose. I listened to him read and analyze essays by Herbert Marcuse, Kimberle Crenshaw, Derrick Bell, bell hooks, Robin DiAngelo, Jacques Derrida, and Paolo Freire. As I was listening, Lindsay was also learning. He traced modern identity politics back through the postmodernists, back to Marx. Marx’s ideas he traced back to Hegel, as he did long episodes about Hegel’s extremely convoluted philosophy and how Marx tried to remove Hegel’s mysticism. Eventually, he uncovered the occult roots of Hegel and other German philosophers. It was from Lindsay that I first heard the term Hermeticism (although I was listening to a lecture on Gnosticism by Michael Heiser around the same time).

Lindsay started out in the New Atheist movement, with a special interest in the psychology of cults. He then disassociated himself from the New Atheists when he noticed they were behaving, as a group, rather like fundamentalists. His views on religion have matured over the years. He now realizes that not all religions are equally cultlike or equally bad for society. And, after much research, he has correctly identified modern identity politics as a reboot of the ancient Gnostic/Hermetic mystery religions, complete with secret knowledge, sexual initiation rituals, and the promise to transform human nature itself into something greater. “Ye shall be as gods.”

If all of this sounds hard to believe, you can find all these lectures on the New Discourses website and most of them on YouTube as well.

I go on at such length about this in order to convey to you just how well oriented I was when I picked up Race Marxism. I had already heard Lindsay lecture on the thinkers he mentions in the book, many of them multiple times. (And for many of them, it takes multiple times to actually retain their concepts, because they are intentionally complex. Not to speak of the way they love to invent words, flex on their readers, equivocate, and even undermine language itself.)

I was really well oriented, baby.

And even so — even so — I found Race Marxism to be a slog.

I honestly don’t think this is Lindsay’s fault. He’s trying to give us the history of a concept (“Critical Race Theory”) that is intentionally obscure. Many different streams of thought have gone into it, and the Theory’s proponents take advantage of this to toggle back and forth between the different meanings of the concepts in their theory. In fact, they use the Theory’s slipperiness as a sort of shibboleth. That way, if someone says something negative about the Theory, disagrees, or even simply states the theory in terms they don’t like at the moment, they can claim that this person has not really understood it.

Critical Theories exploit this confusion by focusing virtually entirely on “systems,” which are almost impossible to pin down or describe accurately, not least since these “systems” really are stand-in descriptions for “everything that happens in any domain human beings are involved in, and how.” That is, when a Critical Theory calls something “systemic,” what it really means is that it has an all-encompassing Marxian conspiracy theory about that thing. When people don’t think that way, Theorists then accuse them of not understanding systemic thought, or, more simply, of being stupid and intellectually unsophisticated. This little trick is very useful to activists because it allows them to call everyone who disagrees with them too stupid to disagree with them and generally tricks “educated” onlookers into thinking the plain-sense folks must be missing something important, nuanced, and complex.

ibid, p. 233

Any book that tries to engage with, pin down, and define a thought system that uses these tactics is going to be a slog. Lindsay has to trace several different lines of thought, so he’s coming at the same concept from a different angle in chapter after chapter. It’s all one big tapestry, so there’s not a clear, natural place to start. The first few chapters feel as if we are going in circles a bit. Lindsay has to quote CRT authors at some length, and they are not good writers. Additionally, because their entire philosophy is based upon envy and hate, even when they are somewhat clear they are unpleasant to read. But he is not going to make a claim about CRT and then not back it up. So, we get things like, “No, CRT is not simply anti-white-people; instead…” [twenty pages later] “… and that’s how CRT manages to be anti-most -white-people while denying the reality of race.”

The book picks up towards the end, when with much blood, sweat, and tears, the basic claims of CRT have been established beyond a doubt and Lindsay can move on to how it affects organizations and what can be done about it.

What will your experience be like reading this book?

I’m not sure.

It depends upon how familiar you are with these concepts already, and how quick of a study you are. It might also help if you do your reading from this book at a time of day when you are fresh. I think part of my problem is that I was slogging through it, often when tired or otherwise unwell. It’s not really the sort of book that you can take to an event, or dip into in a waiting room.

If these concepts are totally new to you, and you are a very quick study, you might come out of this book with the experience of “mind blown!” However, it’s more likely that you will grasp some things on the first go-round, but will understand more each time you re-read a given chapter. (That’s actually my experience with most non-fiction books.)

It is the nature of Critical Race Theory to have a whole bunch of academic, intimidating-sounding terms to describe just a couple of ideas that, when you get down to it, are fairly simple and also stupid. So the learning curve is steep at first, but quickly flattens out if you know what I mean.

I bought this book primarily to have on hand as a resource. I had to read it cover to cover at least once, so that I know where to find things in it. I probably won’t do that again. But I will certainly dip into it, because it documents painstakingly all the ridiculous, counterintuitive, antihuman, incredibly damaging claims that have been made in this theory, and who made them, when and where in what publication. That is an invaluable resource to have on hand, because there will be new terms and new claims soon, and the Theorists will deny that anyone ever made the old ones.

So, I bought this book more as a reference book than anything. I hope that you will, too. Lindsay has done a fantastic job compiling all this stuff and sorting it all out in some kind of order. Perhaps, if he had spent more years on it, he could have polished the prose and made it more pleasant to read, but that wasn’t the priority. The priority was to get this book out there in time to undeceive as many people as possible about this insidious theory. It doesn’t have to be pretty. It just has to exist.