About the Greco-Fiction

This year, I decided that my fiction focus would be novels inspired by ancient Greek myths. I don’t always pick a fiction focus, but this year, things just coalesced.

In the classical Christian school where I teach, we follow a 4-year “history cycle.” Ancient World, Medieval World, Exploration/Renaissance, Modern World. This year, we are cycling through Ancient, so I have been immersed in the Flood, the Sumerians, Abraham, Egypt, and the Iliad and Odyssey. (Somewhat immersed, of course. We could always immerse ourselves more.)

Revisiting Mycenae and Crete, I remembered that back in university (in the last millennium!) I read what I thought was a fantastic book that was a re-telling of Theseus. Looked it up, and it turns out it was The King Must Die by Mary Renault. And it turns out that Renault has a bunch of other books that I’ve never read. (Back in the last millennium, the way we found books was we stumbled upon them in the library.) So, onto the list went at least a re-read of The King Must Die and its sequel, The Bull from the Sea. I bought myself copies of these for Christmas using my husband’s money, so technically he bought me the copies for Christmas.

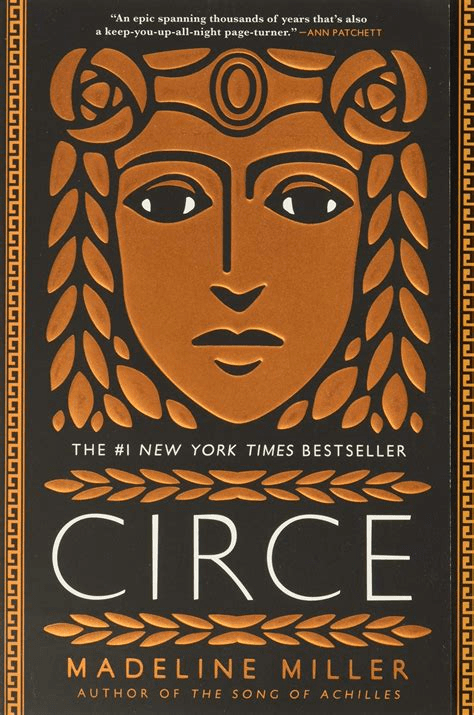

Meanwhile, years ago I had won a copy of Circe, and had been waiting to read it until I was ready to stick my head back in the ancient Mediterranean. I’m also aware that Madeline Miller has at least one more book, The Song of Achilles, which is from Patroclos’s point of view. Gay, of course (and that is historically accurate). I decided I might read that, depending upon how I enjoyed or didn’t enjoy Circe. You can write about ancient Greek events from a hard-core feminist/queer perspective, or you can not. I wanted to know first what approach Miller was taking.

Finally, some of my students have been reading Percy Jackson, with the result that they are already quite familiar with the Greek pantheon. I’d known that the Jackson books were out there, so perhaps now is the year when I read at least a few of them. Jackson went onto the list.

Then there are the rereads. Til We Have Faces is C.S. Lewis’s masterpiece, set probably in Scythia or the Caucasus, near the Greeks but not too near. Moving farther from Greece, we have Taliesin, Merlin, and Arthur by Steven R. Lawhead. I read Taliesin in high school. It’s Celtic, not Greek, except that about half the book takes place on Atlantis, with bull dancing and stuff, so I figure that counts. Now, the Daily Wire has made a TV series based on these books. The events of Taliesin take up about an episode and a half. So, if I have time, I’ll reread/read Steven R. Lawhead.

So, here is the list as it stands …

- Circe

- The Song of Achilles?

- The King Must Die

- The Bull from the Sea

- other books by Renault?

- Til We Have Faces

- at least a couple of Percy Jackson books

- Taliesin

- Merlin?

- Arthur?

This should fulfill the twelve books that I told Goodreads I’m planning on, this year.

In the course of my teaching year, I have already read The Cat of Bubastes with my students, and am now reading Hittite Warrior, which is also very good. Also on the docket is The Young Carthaginian.

So, how was Circe?

I loved this book. It is exactly the genre I like. Miller did a fantastic job keeping track of all the gods, titans, and nymphs, their little feuds, and their family relations to one another.

Circe, in The Odyssey, is a “witch” whom Odysseus and his men encounter on the island of Aiaia (Corsica or Sardinia … I was imagining Corsica). She turns some of them into pigs, but Odysseus convinces her to change them back. She becomes a sort of ambiguous ally, giving him advice about how to handle the Moving Rocks, the Sirens, and Charybdis and Scylla.

Of course, there is always more detail to the story. Miller has researched this deeply, and I appreciate her portrait of where Circe came from. Circe is the daughter of the sun, Helios, who is a titan, and his one legitimate wife. This makes her the sister of Pasiphaë, wife of King Minos (ahem), and also of Aeetes, father of the witch Madea.

Given that she is divine, Circe gets a front-row seat to nearly all the earliest myths. She meets Prometheus in person. She watches the whole ugly episode with Minotaur go down (this is centuries before Odysseus). Time passes quickly for her. At the same time, she is sort of fascinated by mortals. On the plus side, this means she does not view them as disposable, as most of her relatives do. On the down side, she at first fails to see them as a threat.

Near the end of the book, she has this to say.

I thought once that gods are the opposite of death, but I see now they are more dead than anything, for they are unchanging, and can hold nothing in their hands.

p. 385

Though a page-turner, Circe was a heavy read emotionally. As you might expect, it really stinks to be an ancient Greek god or Titan. You are likely to have horrible parents, for example. The hardest part for me was finding out what we might have suspected by reading between the lines: that Odysseus was actually a real [censored], and that things did not go happily after he made it home to Ithaka. Thankfully, Miller does not leave us there but introduces at least one good man and gives the book’s ending a faint note of redemption.

Based on this read, I think I will try The Song of Achilles if I come across it. Miller’s writing is not ideological. It is extremely tragic, with heartbreaking near misses and so forth, but that is actually how these ancient stories go.