I hope you have heard the good news that will be for all people. Unto you is born this day a Savior. He is the Messiah, and also God.

I hope you have heard the good news that will be for all people. Unto you is born this day a Savior. He is the Messiah, and also God.

Adeste fideles, laeti triumphantes

“O come, all ye faithful, joyful and triumphant”

Venite, venite in Bethlehem

“Come, come into Bethlehem”

Natum videte, regem angelorum

“Born see, the king of angels”

Venite adoremus [3x]

“O come, let us adore him” [3x]

Dominum

“The Lord”

Deum de Deo, lumen de lumine

“God from God, light from light” *(these are direct objects, so the subject and verb are coming up)

Gestant puellae viscera

“A girls’ innards carry” (the subject and verb, and by far my favorite line)

Deum verum

“True God” (and still the direct object)

genitum non factum

“Begotten, not made”

Refrain: Venite adoremus, Dominum “O come, let us adore/The Lord”

Cantet nunc io, chorus angelorum

“Now sings it, the chorus of angels”

Cantet nunc aula caelestium

“Now the heavenly court sings”

Gloria, gloria in excelsis Deo

“Glory, glory to God in the highest”

Refrain: “O come, let us adore/The Lord”

Ergo qui natus die hodierna

“Therefore, who is born on the day of today”

Jesu, tibi sit gloria

“Jesus, to you be glory”

Patris aeterni Verbum caro factum

“Word of the eternal Father made flesh”

Refrain

See how the Latin is actually more direct/efficient than the English? Kind of shockingly so?

I think because the original Latin version had so many syllables, to translate the lines into English, additional words had to be added, and sometimes even new ideas such as “Yea, Lord, we greet thee,” which is how the fourth verse begins in English and is one of my favorite lines in that version.

And there was also a daughter.

She drops out of the story very early, sacrificed

for good winds on the way to Troy.

But her mother’s revenge has made history.

And there was also a daughter

cursed to foresee the destruction of the city,

as daughters often do,

and no one believed her.

And there was also a daughter,

kidnapped (seduced?) by Shechem,

avenged (destroyed?) by her brothers,

a single chapter in Genesis.

And there was also a prophet,

a man too young to know what women suffer–

yet He did, somehow.

Daughter, your faith has healed you. Go in peace.

I am not a person who eagerly awaits the latest release in a series, and pre-orders books as soon as they become available. Usually, I am the one who discovers the series 20 years after it came out. In fact, this series by Klavan is the only exception I can think of. I pre-ordered After That, and it came, as promised, on Halloween.

This is the fifth book in the Cameron Winter series. The other books are:

After That, the Dark takes Winter on the next stage of his journey. It’s designed to be readable as a stand-alone, but you will find it more satisfying if you’ve been with him all along.

Like every Winter book, this one deals with Winter’s psychological journey, and on a parallel track there is an equally devastating crime that he is trying to solve and, inevitably, prevent. Subplots include Winter’s love life and his battles with the leftie professors at the university where he is an English professor.

The title for this book is taken from a poem by English Romantic poet Tennyson:

… Who imagined that his death would be like sailing over the sandbar near the coast and out into the greater ocean.

Twilight and evening bell,

And after that the dark!

And may there be no sadness of farewell,

When I embark;

For tho’ from out our bourne of Time and Place

The flood may bear me far,

I hope to see my Pilot face to face

When I have crost the bar.

ibid, p. 160

Cameron Winter’s academic specialty is English Romantic poetry (about which Klavan recently published a book, himself). Throughout this series, it’s sort of felt as if Klavan wants to have the best of both worlds with his hero. Winter is a former government operative, a dangerous man, and also a soft, spiritual guy who just wants everyone to appreciate poetry. Sort of like a medieval knight. I haven’t felt that this tension was 100% successful in past books, although it does lead to the Superman dynamic where the nerdy guy takes off his glasses and messes up the bad guys good, which is always fun. But in this volume, Winter starts to integrate these two different sides of his personality.

The crimes in this book deal with transhumanism. The victims and potential victims are mothers and babies. One potential victim is an expectant mother who has noticed changes in her husband and can’t articulate them well enough to get anyone to believe her. It’s the kind of thing I wouldn’t have been able to handle a few years ago, when my kids were smaller. I kept reading only because this is Klavan, and I know he doesn’t like stories where women get butchered gratuitously. “Look, when there’s a killer chasing a girl with a knife, I’m on the side of the girl!”

So, if you like poetry, action scenes, demonic possession, or personal growth, you will get all of that here. It’s not exactly like any other action/crime book I’ve read. The hero is usually wrestling with his own demons, but in other books he doesn’t spend so much time talking to his shrink. It’s a bold move on Klavan’s part to allow the hero to actually start beating the personal demons. I don’t know how he’s going to continue a noir-type series once his hero becomes psychologically healthy, but I’m sure he’ll find a way.

As you can see, I’m a little conflicted about Cameron Winter. But I still wholeheartedly give this book five stars, and if you want to find out why, read on for some major spoilers.

I have mentioned before that what I live for in books is when the characters’ concrete experience and myth coalesce, so they are walking the specific path in front of them, but also enacting a mythological scene at the same time. This is a little hard to describe, but you know it when you see it. It’s what makes great art.

This fusion of the everyday and the eternal is most often found in the fantasy or sci-fi genres, because to be honest, it’s easiest to set up there. But to my delight, Klavan has here pulled it off in a modern thriller/true-crime type novel.

Let’s go back to the pregnant woman who starts to suspect her husband. Her name is Tilda, a name probably chosen for how vulnerable it makes her sound. Tilda used to be a “bar girl,” one of the town’s easy marks. Then, her husband Martin picked her up with the line, “Do you have a minute to talk about Jesus Christ?” Tilda thought that was a pretty good joke, but then Martin actually did. He actually did talk to her about Jesus Christ. And he was a perfect gentleman. Tilda married him, and she became a Christian and her life completely changed. But now, the man who led her to this change seems to have become a completely different person and Tilda, understandably, doubts herself. Sometimes, she secretly wonders whether she’s really faking this whole Jesus thing.

Winter, meanwhile, is on the track of a man he knows is out there. He knows this man will have undergone a dramatic personality change recently, and that if not found he will begin to commit gruesome crimes. Winter, though an atheist, is dating a Christian girl and she has given him a cross for his spiritual protection. Winter keeps the cross in the coin pocket of his jeans. When the bad guys, after beating him rather severely, have him handcuffed to a chair, he is able to get the cross out and use it to pick the locks on the cuffs. There follows an action scene wherein Winter, still holding the cross, manages to escape the bad guys and run barefoot into a cornfield. As he runs, a cornstalk punctures his foot. When he finally stops running and wonders why his hand hurts, he looks down and finds that the cross has pierced the inside of his fist. He has to dig it out.

When I read that, I looked up and said to my husband, “The hero just received stigmata.”

But Klavan isn’t done with Winter yet.

Tilda, meanwhile, is tied up in the crawlspace in a house her husband has been working on. She knows her husband is about to come and finish her off. Her mind is a hurricane of incoherent prayers for Jesus to spare her unborn baby.

Then Winter shows up, having already decommissioned the husband outside. Because he has been beaten so badly, his face is a swollen mess, “like a monster.” And the first thing he says to Tilda is exactly what I knew he would say:

“Don’t be afraid.”

This is how Jesus comes to us. “His appearance was so disfigured beyond that of any human being, and his form marred beyond human likeness.” (Isaiah 52:14) He shows up looking like that, and He says to us, “Fear not.”

As Winter strives to calm Tilda down enough to rescue her, he keeps saying the sorts of things that Jesus says:

“Listen to me,” the man said. “I’m going to use a knife. No, no, it’s all right, don’t be afraid. I’m going to use a knife to cut you free. It will look scary, but I will not hurt you. Nothing will hurt you now, but I have to cut you free. Don’t be afraid.”

… The man had climbed out of the space. He was above her again, reaching down for her with both hands.

“[Your husband] is not here. Let me get hold of you. Don’t you hold on to me,” he said. “I’m stronger. Let me hold on to you.”

… Tilda was crying hard now. “I prayed to Jesus and you came,” she explained.

“Oh. Well, good,” said the man. “It’s nice when things happen that way.”

ibid, pp. 305 – 307

That last line, by the way, shows that Klavan is not trying too hard with Winter. Nor is he writing an allegory. This kind of double vision in a book is all the harder to do when you let it grow naturally out of the story and don’t force it. Kudos.

Sometimes, you get into a discussion in a comments section that clearly is beyond the scope of the comments section, both because a) it requires really long comments, b) with footnotes, and c) your interlocutor is not actually going to be convinced. In other words, this discussion ought to be a persuasive essay instead.

When you have a theology blog, this is nothing but good news.

I recently got into such a discussion.

The context: Doug Wilson’s interview with Ross Douthat. Douthat asks Wilson whether, in his ideal Christian Republic 500 years from now, every sin would be against the law. Wilson makes the helpful distinction between sins and crimes. Not every sin should be against the law, he says. Failure to understand this concept got the Puritans into trouble, but we have learned a lot since then. Wilson then goes on to mention the well-known classification of “three types of law” found in the Old Testament: the moral law (universal, binding on all individuals before God), the civil law (what was legal and illegal in the kingdom of Israel, and with what civil penalties), and the ceremonial law (regulations having to do with the Temple, the sacrificial system, and various purity laws such as food laws). If you have been around Christian circles, particularly Reformed circles, you will have heard this distinction. (Edit: I’m now not sure whether Wilson brought up the three categories of law in the video, or whether it came up in the comments as we discussed the distinction he was making between sin and crime.)

Now we come to the commenter who kindly gave me a prompt for this essay. I don’t even know whether this person is man or a woman, but I’m going to call him Rufus.

Rufus says,

The problem is that the distinction [between sin and crime] is always arbitrary, and tends to align with the cultural norms of a particular period of time (e.g. USA in the 1950s).

The inconvenient fact is that moral/civil/ceremonial law distinctions are not in the text, either explicitly or implicitly based on the arrangement (e.g. if you read straight through Leviticus and Deuteronomy, you will find yourself constantly flipping between categories, sometimes verse to verse, without any indication you should be doing so.)

What you are doing is looking at the text vs. normative Christian practice and trying to figure out a system that explains why we follow some of the commandments and not others. Then once you have devised the system, you apply it to the text and say that’s why we follow these and not those. This is a circular argument. The fact you can’t explain satisfactorily how Matthew 5:18 – 20 fits with normative Christian practice is why the Hebrew Roots movement exists. Their position is wrong, but it’s totally reasonable given the premises they’re starting with.

Thanks for the prompt, Rufus. This will give us a lot to chew on.

First, let me clear up just a few simple misunderstandings that Rufus can hardly be blamed for.

Rufus mentions, or implies, that Wilson is just taking a sentimental look back at 1950s America and assuming that, if he can get his Christian republic to look like that, he will have applied the law of God in a culturally appropriate way. Now, it happens that Wilson, in this interview and elsewhere, does mention 50s & 60s America as a place he remembers fondly. He usually brings it up in order to make the point that sodomy was banned back then, and yet America did not resemble the Handmaid’s Tale, which must mean laws against sodomy don’t necessarily produce that kind of society.

However, if Rufus knew Wilson a little better, he would know that Wilson does not look back at the 1950s with a sentimental and uncritical eye. In fact, Wilson has compared the position of the U.S. in the 1950s to that of someone who has just fallen out of an airplane, but is still only a yard below it. Now, we are approaching the ground, but going back to one yard below the plane, if we could do such a thing, would not help in the long run.

If Rufus knew the neoReformed world from within Wilson is writing even better, he would know that, when we do romanticize historical eras, it ain’t the 1950s we usually choose. It’s more likely to be Jane Austen’s England, or Knox’s Scotland, or Jonathan Edwards’s Puritan New England. This shows that Rufus does not really know who he is talking to. He can hardly be blamed for this, on the Internet, but if he wants to attain a “touche” moment, he needs to find out the actual position of his interlocutor, not talk to somebody he has in his mind (maybe a Southern Baptist?).

Then Rufus says to me (or perhaps it’s a general “you”), “What you are doing is looking at the text vs. normative Christian practice and trying to figure out a system that explains why we follow some of the commandments and not others. Then once you have devised the system, you apply it to the text and say that’s why we follow these and not those. This is a circular argument.”

Why yes, it would be a circular argument, if that were something I was doing. And perhaps there are some people who do that, and these are the people Rufus had in mind as the intended audience for his comment. However, I am not those people. I am a person who lived overseas, trying to get a Bible translation movement started in jungle area that boasted a lot of paganism still, a strong Muslim presence as well, and heavy influence from Christian norms that were not American Christian norms. Both before and after living there, I took anthropology and missiology classes where almost all we did was discuss how the Bible can and should be applied in different cultural contexts. I’ve prayed with native people who use their language’s name for the Creator (Mohotara), and it was glorious. I’ve attended a traditional dance ceremony that had been adapted for Christian purposes to give thanks for something. I’ve listened to people discuss whether Christians can keep in their homes heirlooms that were once used for pagan purposes, and what happens when a Muslim man with multiple wives converts to Christianity.

So no, Rufus, if I was the intended audience for your comment, you have me wrong. I was not just taking a received American Christian practice and backfilling it to make it look biblical. But there is no way you could be expected to know this. After all, I don’t even know whether you are a man or a woman.

O.K., so my claim is that people who talk about the three categories of the Law are not just arguing in a circle, or justifying sentimentality or lazy thinking. What is our biblical argument, then? Let’s address Rufus’s exegetical objections.

First, let me say that Rufus is technically right in his comments about Leviticus and Deuteronomy:

The inconvenient fact is that moral/civil/ceremonial law distinctions are not in the text, either explicitly or implicitly based on the arrangement (e.g. if you read straight through Leviticus and Deuteronomy, you will find yourself constantly flipping between categories, sometimes verse to verse, without any indication you should be doing so.)

Rufus 100% is correct that nowhere in the Law are there headings that say “Moral Law,” “Civil Law,” or “Ceremonial Law.” He is also correct that all these three types of commands tend to be mixed together, and sometimes it’s hard to tell which one a given commandment is. In this essay, I will argue that his correctness about the distinctions being “not in the text” only holds if you confine yourself to the texts of the actual commands, ignore the narrative parts, ignore the New Testament, and play dumb.

First, let’s acknowledge that the Books of the Law (Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy) strike the modern person as disorganized. These books toggle back and forth between law and narrative. They give the Ten Commandments, and then a bunch of differing elaborations on them in different places, organized in different ways depending upon the book, the passage, and what is foregrounded after the narrative that just took place. Sometimes, Israel acts up, God says He’s going to reject them, Moses talks Him around, and then all the commands are repeated as they are reiterated. In Numbers, new applications and case law are given as new situations arise (for example, how inheritance should work if a man has only daughters). Some of the annual ceremonies (not to mention the daily ceremonies) work differently when the people of Israel were dwelling in tents with the Tabernacle right there, versus when they were living on their homesteads throughout the land, days, or weeks’ journey from the Tabernacle and later the Temple. So, no, the laws are not organized and laid out conveniently, the way modern people would like a code of laws to be. In some ways, they are more like a tribal history, which is how laws often worked back then.

In fact, I’ll do you one better. The narrative accounts from the times of the patriarchs and Exodus are also mysterious and confusing. All this was so long ago, and so little is known about the context, that it can be difficult to re-construct, for example, Israel’s exact route out of Egypt, despite the many, now obsolete, place-names given. So yes, this is an ancient, ancient document, not a simple user’s manual.

But the distinction between ceremonial, civil, and moral law is far from the only distinction that was not present in the ancient mind, and emerged over time with progressive revelation. Another great example of this would be the doctrine of the Trinity. In the Old Testament, we often see the LORD appearing as a man. Sometimes “the Angel of the LORD” does the same thing, and very occasionally, such as in Genesis 18, we see them together. (See Michael Heiser and his discussion of “two powers in heaven” in his book The Unseen Realm.) We also see “the spirit of the LORD” coming upon people in the Old Testament. The result was usually that they prophesied, or had a kind of battle madness come upon them. Thousands of years later, in the New Testament, we see Jesus say that He is God’s Son, and that “I and the Father are one.” We see the Spirit come down upon Jesus in the form of a dove. In John 15 and 16, Jesus talks openly about both the Father and the Spirit. Finally, in Matthew 28, we get “Baptize them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit.” You could not get trinitarian doctrine out of just Leviticus and Deuteronomy, but if you take the whole Bible as inspired, you can’t avoid it.

C.S. Lewis has said somewhere, I think in The Abolition of Man, that the ancient mind did not make a distinction between spiritual and physical. When ancient people saw a king’s throne, for example, they reacted to it as a totality. The physical throne and the concept of majesty and authority were one thing. As time has gone by, and humanity has made a sharper and sharper distinction between physical and spiritual, we can readily infer when the ancients were talking about one, the other, or both.

In the same way, once we have been given the “three categories of law” as a tool to help us in reading Leviticus, it’s usually pretty easy to tell which kind we are looking at. Civil laws usually come with some kind of civil penalty, anything from remuneration to death. Moral laws are usually just commands: “If you see the donkey of one who hates you falling down under its load, do not leave it there; be sure to help him with it.” (Ex. 23:5) Ceremonial laws are often prescriptions of how to handle ceremonial objects and what sacrifices to offer; the subclass of ceremonial laws called purity laws usually come with some kind of purification ritual if someone becomes “unclean.” All this may not be explicit, but neither is it arbitrary.

Now, we acknowledge that these categories are not completely watertight in the context of ancient Israel. Some offenses are both civil and ceremonial, and these often call for death. Examples would be a wide range of sexual offenses that not only wrong the victim, but also defile the nation and dishonor God. Some offenses are just ceremonial but not civil or moral: touching a dead body. Some are both moral and civil (false testimony in court), where others are just moral (envy, gossip). Having said all this, you can usually tell the category(-ies) of the offense by using common sense.

Finally, I’d like to call Rufus’s attention to the fact that the New Testament exists. The question of the difference between a sin and a crime, and of what parts of the Old Testament Law were binding on non-Jewish believers, occupies large swathes of the New Testament. I mean large swathes. This is discussed at length.

The entire book of Hebrews establishes that the ceremonial law was a preparation for Christ, was fulfilled by Christ, and now is no longer necessary. Hebrews was written not too long before the destruction of the Temple in 70 A.D. It warns repeatedly that the whole sacrificial system is “passing away.” Galatians discusses at length whether circumcision, a purity ordinance designed to differentiate Israel from other peoples, is necessary for a Christian to practice (answer: No). Large chunks of Acts are devoted to early believers trying to figure out which parts of the Law are binding on Gentile converts to Christianity. God Himself reveals to Peter that the food laws no longer apply. This gives us a pretty good case that the ceremonial laws associated with temple system, and the purity laws associated with separateness, are their own category.

But there were some prohibitions that were moral, civil, and ceremonial offenses in old Israel, which now are just moral offenses. Fornication, adultery, and sex with temple prostitutes are prime examples. These things were legal in the Roman empire. They are not ceremonial offenses for Gentiles who are no longer under the ceremonial law. But Paul is at some pains to point out in his letters that they are still moral offenses against God. (“Then they should not be illegal in a Christian republic!” Whether they should be civil offenses, they were not in the Roman empire. This shows there is a distinction between moral law and a civil law.)

There is also a fair amount of discussion in the New Testament as to what should be the Christian’s relationship to the civil magistrate — the legal system of the country they live in. In Luke 3:14, when Roman soldiers ask John what they should do to demonstrate repentance, he doesn’t tell them to quit working for Empire, but he tells them not to be corrupt and oppressive. Paul says that Christians should be known as law-abiding (Romans 13:4). He seems to feel that the civil magistrate has actual real authority to enforce civil laws, but that he should not get involved in disputes within the church (I Cor. 6). Similarly, Jesus tells us that paying taxes to pay for law enforcement and national defense should not burden our conscience (Matthew 22:15ff). If someone who has legal authority over others becomes a Christian, Paul (Philemon 1 – 25) and Jesus (Matt. 24:48) say that they should use their authority to do good. Jesus also says that we should use our wealth to do good (Luke 16:9). The general picture is of two different spheres of authority, which overlap in commonsense ways. A Christian may have to engage in civil disobedience if ordered to bow down to the golden statue, but he is not culpable merely by virtue of participating in the system in which he finds himself, and should be law-abiding except in extraordinary circumstances. A Christian who finds himself with some civil power should use that power like a Christian: don’t be corrupt (the prohibition on taking bribes goes all the way back to Exodus), and try to use your influence to do as much good as possible. Long-term, this was going to lead to things like the abolition of sex slavery, then polygamy and wife-beating, and then slavery in general. But the early church could not dream of such influence.

In sum, the New Testament has a lot to tell us about ceremonial, moral, and civil law, but it is not neatly organized. It is in the form of letters and narrative history.

So now we can address Rufus’s claim that “you can’t explain satisfactorily how Matthew 5:18 – 20 fits with normative Christian practice.”

I tell you the truth, until heaven and earth disappear, not the smallest letter, not the least stroke of a pen, will by any means disappear from the Law until everything is accomplished. Anyone who breaks one of these commandments and teaches others to do the same will be called least in the kingdom of heaven, but whoever practices and teaches these commands will be called great in the kingdom of heaven.

You are right, Rufus, but again, you are only right if we squint and play dumb. I can certainly explain it if you back up and include Matthew 5:17:

Do not think that I have come to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I have not come to abolish them but to fulfill them.

Jesus fulfills the Law and the Prophets. How does He do it? By being the last High Priest we’ll ever need (Hebrews 7), the last sacrificial lamb we’ll ever need (John 1:29), the true temple (John 2:19 – 22), the true Ark (I Peter 3:20 – 21), the one for whom the prophets searched intently (I Peter 1:10 – 12), the second Adam (Romans 5:12 – 21), and so on. When His ongoing work is done, then “everything will be accomplished.” At the moment, He has accomplished a lot of it, including making the ceremonial law obsolete. At the time He was speaking in Matthew 5, He had not yet accomplished a lot of this, so the ceremonial Law was still in full force. For a little while.

Jesus did take major issue with how the Law was being applied (all out of emphasis, and contrary to its own spirit). He had been so outspoken about this that some people got the impression He was throwing out the whole thing, and they didn’t know whether to be excited or terrified. In Matthew 5:17 – 22, Jesus hastens to clarify that He is still on the side of the Lawgiver. He wanted us to know that, although large parts of the Law were shortly going to be “accomplished,” they were never going to become wrong. That book is closed, you might say, but it is not burned. It will never be the case that God was wrong to give the Law He gave to the ancient Israelites. It will never be the case that that Law was not good. We cannot accuse God of giving an imperfect Law, which I think is the main point of this passage.

O.K., that’s it. Rufus, if you’re out there, you say that you have looked into these issues deeply, “for decades.” I don’t know what your experience has been. Clearly, it has differed from mine. I hope we can stop talking past each other.

This review was originally posted, in a slightly different form, on Goodreads in June 2025.

This book is a capable history of New Thought in the Christian church, particularly in America. The author first sketches how she grew up around a lot of New Thought and mistook it for Christianity. Then, she sketches how after she realized many of these beliefs were wrong, for some years she was calling them New Age because that’s what everyone else called them. She discusses how she learned of the term New Thought and how it differs from the New Age.

Both belief systems partake of Gnostic/Hermetic cosmology and theory of human nature. However, New Age embraces neopaganism and the occult, whereas New Thought instead tries to cast these Hermetic ideas in “Christianese” and read them back into the New Testament. This is made easier because many New Testament writers were talking directly back to Gnostics, and even re-purposing their terms.

Melissa unpacks the Gnostic/Hermetic assumptions behind such common “Christian” practices as the Prosperity Gospel, visualization, affirmations, “I am” statements, and the like. But instead of just dismissing these practices as “ppf, that’s pagan,” she actually shows where they originated and how they differ from orthodox Christianity.

This book does not dive deeply into the pagan side of Gnosticism and Hermeticism. It doesn’t discuss these philosophies’ relationship to Western mysticism, Eastern mysticism, Kabbalism, or German philosophers like Hegel. It doesn’t discuss the attempts in the early centuries after Christianity to integrate Gnosticism with Christianity. The history of these philosophies is a huge topic that could take up a lifetime of study.

Melissa’s book is not meant to be an intimidating doorstop of a book that covers all of this. She’s zooming in on one little twig on this big, ugly tree: New Thought and its influence on American Christianity. Her book gives well-meaning Christians the tools and vocabulary to recognize this kind of thought and to talk about it. I have bought copies to give to all the women in my family. New Thought can be difficult to talk about because it portrays itself as “what Jesus actually taught.” If you know someone who is into New Thought, you cannot just dismiss it as “No, that’s Gnostic.” Even though you are right, to them it will sound like you’re just brushing them off. This book might be useful in such a situation.

If you want to find out how Hermeticism gave birth to Marxism through Hegel and Marx, there is a fantastic series of lectures about it on YouTube by James Lindsay. I also recommend Melissa’s YouTube channel and the YouTube channel Cultish.

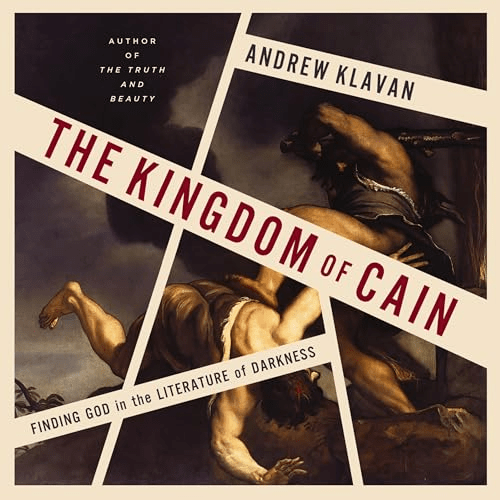

A review of noir writer Andrew Klavan’s The Kingdom of Cain: Finding God in the Literature of Darkness. I have already posted this review on Amazon and Goodreads.

This is a very readable book that fleshes out Andrew Klavan’s thesis:

The opposite of murder is creation–creation, which is the telos of love. And because art, true art, is an act of creation, it always transforms its subject into itself, even if the subject is murder. An act of darkness is not the same thing as a work of art about an act of darkness. The murders in Shakespeare’s Macbeth are horrific, but they are part of a beautiful play.

page 17

In other words, Klavan is wrestling with the problem of evil. Based on his decades of thinking about this, he has concluded that in this life, there is no theological answer that can redeem evil for those who have suffered it. Theological answers there may be, but those are not what redeem it for us. The only answer to suffering is not an answer, exactly; it is beauty. The example he frequently re-visits is the Pieta, “the most beautiful statue in the world,” a statue of Mary cradling her maimed and innocent, dead son.

I think Klavan’s thesis is a very strong one. I think of the book of Job. Job suffers horribly, and apparently undeservedly, and to add to his suffering, he is told that it must be his fault. He asks God why. Now, as it happens, there is an explanation for everything that is happening to Job. But God doesn’t give it. He just starts talking to Job about the wild animals and their habits. This is beauty, it is wonder, and it is far beyond Job’s experience. But ultimately, God answers Job with Himself, with His presence. He answers Job out of the whirlwind. He mentions just a few of His mighty, mysterious works in creation. And this is a good answer. It is enough. It is a much better answer than if God had said, “Well, it all started when I got into this argument with Satan …”

Kingdom of Cain is a hard book to read because of the real-life crimes described in it. Klavan tries not to get too graphic unless he has to, but this is a book about murders after all, including copycat murders. The blurb says it examines the impact of three murders on our culture, but there are a lot more than that, both fictional and–this is the hard to read part–real. The hardest one for me was the kidnap, rape, and murder of a 14-year-old boy by a pair of older teenagers who were later lionized in fiction.

This book is very insightful. Perhaps if I had never heard Klavan make these points before, I’d have given it five stars. But I have been following him for years, and he has been working on this concept for years, so the idea was not new to me. Especially in the later chapters, it felt a little belaboring. Hence, four stars.

The Law of Attraction isn’t biblical. It’s anti-biblical. It’s occultic, not Christian. It makes Jesus your life coach and God your loyal servant. But “believing in Jesus” is not a magic formula. And God isn’t your golden retriever.

Happy Lies, by Melissa Dougherty, p. 141

(Is the above really the latest Sunshine Blogger Award logo? Looks kinda messy.)

So, Bookstooge sort-of-nominated me for the Sunshine Blogger Award! Thank you, Bookstooge! I am so flattered. I think his exact words were, “If you’re reading this, consider yourself nominated, because it means you have a pulse.”

It’s because they are trying to categorize things according to algorithmic rules/decision trees instead of the way the human mind normally works, which is by constructing a schema for the thing in question and then eyeballing it.

With schemas, if the thing mostly resembles the schema, it is considered an instance of that thing, even if it misses checking some important boxes. And if it checks all the boxes but manifestly does NOT resemble the schema at all, then it’s not an instance of that thing.

Cereal is in the latter category. It’s an ungodly modern creation of Mr. Kellogg, who believed that eating meat was morally wrong as well as unhealthy, and sought to banish it from the breakfast table. And I say this as someone who very much likes breakfast cereal, particularly as an evening snack, even though I know it has wreaked havoc with my metabolism (see question #10).

2. Why Do You Blog?

I blog to get you interested in my books. Go buy ’em. BUT, warning, don’t buy the Kindle version of The Strange Land until the end of next week, when it will cost 99 cents because of a special promo.

3. How Do You Justify Your Existence? (I got that one from the Tales of the Black Widowers, good isn’t it?)

Yep, it’s a good one.

“So God created man. In the image of God created He him, male and female created He them. And He said to them, ‘Be fruitful and multiply, fill the earth and subdue it. Rule over the fish of the sea and the birds of the air, the cattle and the creatures that move along the ground.'”

Edit: By quoting this passage, I am NOT asserting that the only justification for our life is to reproduce … i.e., that your life somehow has no meaning if you are not a parent. I happen to have been given three children, but that’s God’s gift to me, not mine to Him. No, the point of quoting this passage is this: I justify my existence because God made me. He made us. He wanted there to be people. He wanted us to exist as male and female. And, per the latter part of the passage, He wanted there to be a lot of us. If you exist and you are a human, He is happy about that.

4. How Do You Choose Who to Follow?

Unfortunately, I’m a lot like Trump in this way. If you say nice things to me, I like you and then I follow you.

An alternative route is that you posted something that really interested me. This usually means book reviews, discussion about writing, theology, ancient history, and sometimes art.

5. If John McClane and John Wick were tied on a railroad track and you could only set one of them free, which would you choose and why?

O.K., I had to duckduckgo him, but John McClane is the Bruce Willis character in Die Hard. I would save John McClane instead of John Wick for the following reasons:

6. In a game of Parcheesi, who would win, Spongebob Squarepants or the Doom Slayer?

I expect Spongebob to win in the same way that Bugs Bunny would.

7. Do you feel guilty about all of my oxygen that you are breathing?

Yes. My gosh, don’t remind me!

8. What is your favorite movie?

It’s a tie between The Princess Bride and a little hidden gem called Undercover Blues.

9. If you were going to be “accidentally but on purpose” killed tomorrow, how would you spend today?

I would write long letters to each of my children. If I had extra time, I’d move on to my husband, then other close family and friends.

I might try to transfer the rights to my books so they don’t go out of print, but I don’t think that could be done in one day. If you snooze, you lose, and I guess I snost and I lost.

10. Are mirrors Friend, or Foe?

Friend, but only in the sense of “faithful are the wounds of.”

11. If you could change ONE THING about your blog, what would it be?

Every single visit to my blog would result in a book purchase and then a breathless review on Amazon GO BUY MY BOOKS PEOPLE!

I nominate seven friends (the number of perfection!) plus Bookstooge cause I want to hear his answers too. And I nominate you, Reader, if you want to do it! After all, you are breathing! Which might provide the answer to my first question!

It’s been an emotional week.

But that’s partly my own fault. After all, I had to go and listen to this heartrending testimony …

Jonathan Gass’s story is remarkable for how it consisted of essentially unremitting pain until he came to Christ … and then, for how fast he came to Christ and was transformed.

I say remarkable, but I don’t say unique. Many, many other men and women out there are, as we speak, going through the same unremitting pain. This does not make his story easier to listen to. But look at the peace on his face now.

And then, the same week I listened to Jonathan, I was reading my class of elementary-school students The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, and I came upon this passage:

For a second after Aslan breathed upon him the stone lion looked just the same. Then a tiny streak of gold began to run along his white marble back–then it spread–then the color seemed to lick all over him as the flame licks all over a bit of paper–then, while his hindquarters were still obviously stone, the lion shook his mane and all the heavy, stone folds rippled into living hair. Then he opened his great red mouth, warm and living, and gave a prodigious yawn. And now his hind legs had come to life. He lifted one of them and scratched himself. Then, having caught sight of Aslan, he went bounding after him and frisking round him whimpering with delight and jumping up to lick his face.

The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, p. 184

Aslan turns him back into a lion, and he immediately starts behaving like … a lion.

But not only the individual creatures, but the Witch’s house itself is a picture of a human soul:

“Now for the inside of this house!” said Aslan. “Look alive, everyone. Up stairs and down stairs and in my lady’s chamber! Leave no corner unsearched. You never know where some poor prisoner may be concealed.”

But at last the ransacking of the Witch’s fortress was ended. The whole castle stood empty with every door and window open and the light and the sweet spring air flooding in to all the dark and evil places which needed them so badly.

[And when the castle gates had been knocked down from the inside], and when the dust had cleared it was odd, standing in that dry, grim, stony yard, to see through the gap all the grass and waving trees and sparkling streams of the forest, and blue hills beyond that and beyond them the sky.

ibid, pp. 187 – 189