When I went to see Sage Wall, we stayed in Butte, Montana (pronounced byoot or biut), which is a relatively short drive from my house by the standards of the American West. Butte is a mining town, once known as “The Richest Hill in the World,” although generally, the riches were being spread thin, not going to the people who actually lived there. The riches are copper, silver, and, I believe, opals. If you have more time than we had, Butte has many things like rock shops and a mining museum. You can see little mining towers dotted all over the landscape.

A view of Butte, looking down from the hill above the town.

This plaque talks about women in Butte when it was a boom mining town. Sadly, Old West boom towns are notorious for having a lot of brothels, and Butte was no exception.

Over the town looms the hill itself, and in this hill is a huge, sandy-colored strip mine known as the “Berkeley Pit.” My husband, being the explorer that he is, wanted to visit the Pit. We got there just after the viewing platform closed, so instead, we drove up into the hills above and behind the Pit so as to get a glimpse into its depths.

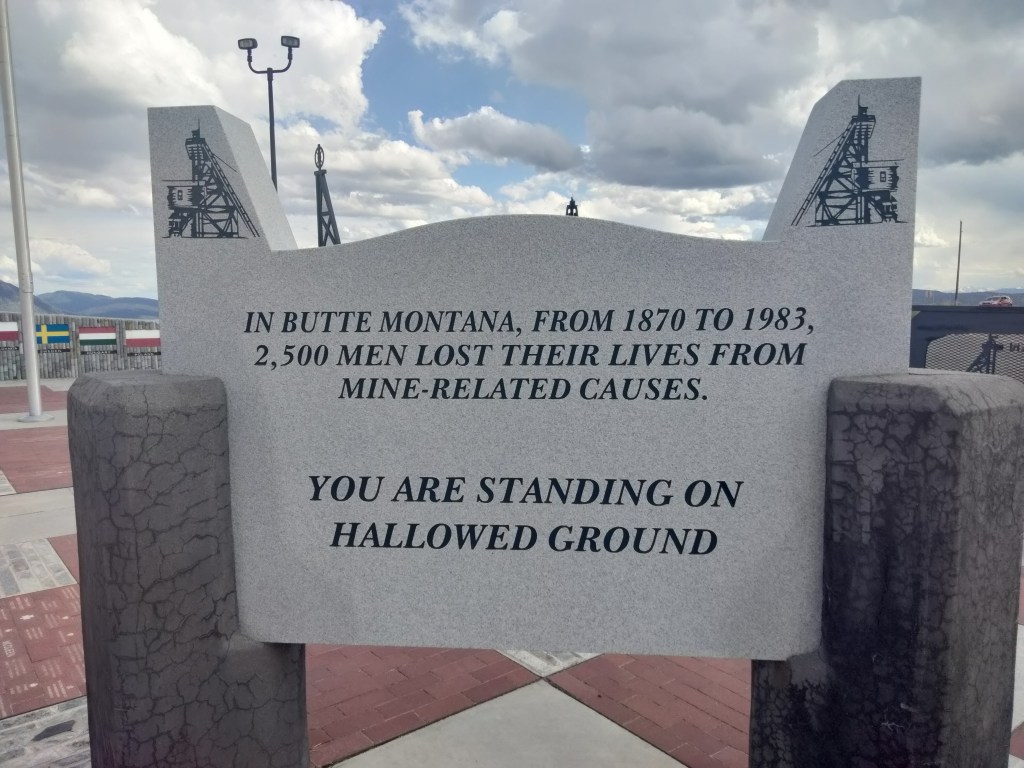

And lo and behold … on a lookout point that overlooks one section of the Pit, we found this monument to fallen miners.

The monument is a large, paved area with the U.S. and Montana flags in the middle, surrounded by a wall on which informational plaques are mounted. I’m going to let my photos of the plaques do most of the work in telling you this story.

The flags you see in the background represent the nationalities of the miners who lost their lives in the disaster.

This prominent central plaque gives some basic information about the Granite Mountain Fire in June of 1917. The fire did not take place in the Berkely Pit, but in an underground mine. A cable, which was covered in a paperlike covering, broke and fell down a shaft. A group of miners went down to inspect the damage, and the paper covering on the cable was accidentally caught on fire by one of their headlamps.

This plaque, filled with names of men lost in the fire, is one of several.

The fire quickly filled the mine. Groups of miners, trapped in tunnels, built barricades (“bulkheads”) to protect them from the fire while they awaited rescue. Sealed off like this, their main danger became the limited air supply, plus fear and despair as their food and water ran low and their lamps began to go out.

Some of these men wrote letters to their loved ones. Here is one.

The town of Butte essentially stood vigil for several days. Firemen worked around the clock to put out the fire and rescue miners. Restaurants stayed open and gave meals to the rescue workers. Grocery stores provided for the families of missing miners. People went into churches to pray for their loved ones.

The plaque below describes Butte as “the strongest union town on earth.” My feelings on unions are mixed to say the least, but I can certainly understand the need for them in the early days of mining.