A tell is, essentially, a man-made hill that consists of layers upon layers of ancient ruins.

I first heard about tells in a Biblical Archaeology context. The Levant is filled with tells. Often, the original city was built on a high spot to begin with. Then, as successive generations of the city were destroyed and rebuilt, the tell got higher and higher. In the Levant, you often find a current city still thriving on top of the tell. So there is a modern city on top of a medieval city on top of a Greco-Roman city top of an Israelite city on top of a Canaanite city on top of a city from the time of Sumer. If you dig down carefully through these tells, you will find mosaics, pots, coins, garbage, all kinds of good stuff. Tells are different from grave mounds because they don’t usually contain grave goods carefully selected, but rather the debris of everyday life, and often the ash layers of past battles.

Well, it turns out, the Levant ain’t the only place that gots tells! I am currently reading The Civilization of the Goddess: The World of Old Europe, by Marija Gimbutas, published in 1991. As you can tell (haha!) from the title, Gimbutas has her own spin on the history of Old Europe, about which I will no doubt post later. But today, I am just here to talk about tells. There are many tells in Thessaly, Macedonia, Bulgaria, Yugoslavia, Romania, western Ukraine and southern Hungary (as we call them today) which show that in the 6,000 to 4,000s B.C., the Balkans were a happenin’ place. They revealed tidy planned cities, sometimes of a few thousand people, with hearths, idols, loom weights, and “exquisite” pots. (I love it when archeologists call something like a pot “exquisite.” It means they are really excited about it.)

I have previously posted about the Vinca Signs, which came from this culture area and may have been an alphabet, though Gimbutas looks like she’s gearing up to treat them as primarily religious symbols. The settlements in this area are all fairly uniform, especially in their earlier stages, which says to me that people spread out quickly, probably from the Levant via Turkey and Macedonia. The climate at the time was rainier than now, which made farming easier. The sea levels were probably also lower, which might have facilitated travel.

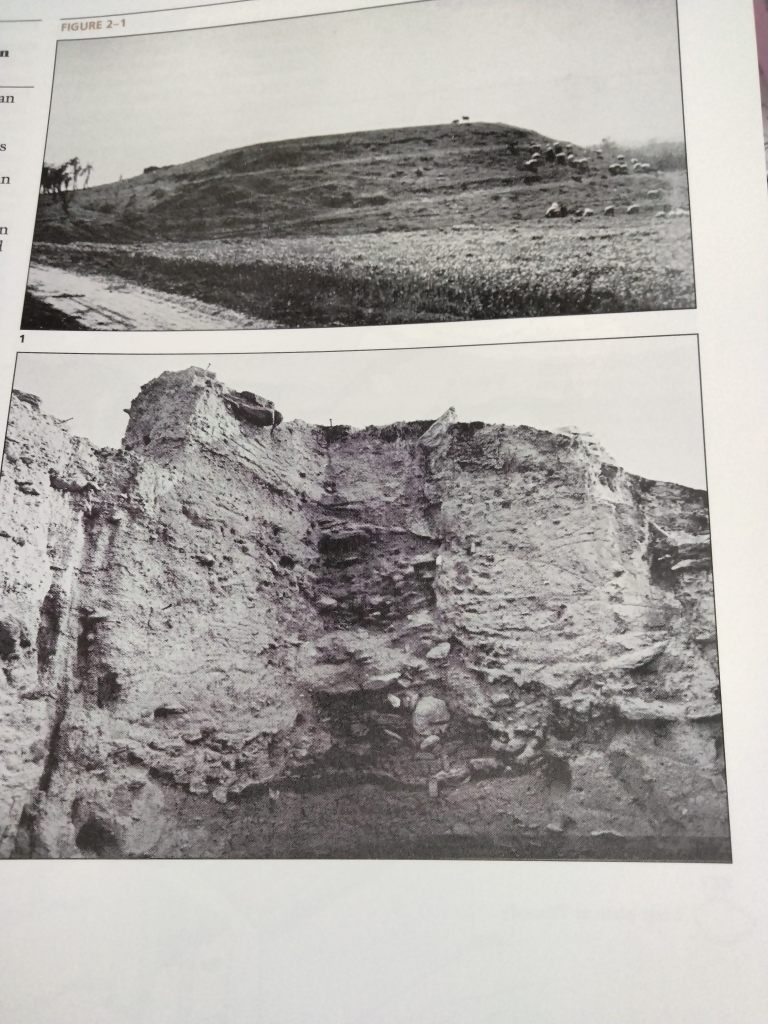

Take a look at the photo at the top of this post. It comes from page 13 of Gimbutas’ book. The upper image is labeled “Argisa tell, west of Larisa, Thessaly.” The lower one: “Profile of Sesklo tell, c. 12 m of cultural deposits, with Early Neolithic (Early Ceramic) at the base and classical Sesklo on the top, c. 65th – 57th cents. B.C.”

Twelve meters of cultural deposits! Imagine the riches.

At the time this book was published, a few tells in the Balkan area had been excavated (Sesklo by Gimbutas herself), but most had not. I expect that is still true today. There have been some “hills” in Bosnia that turned out to be pyramids and to have tunnels inside, but really, even archeologists like Gimbutas who realize that Old Europe was much more advanced than previously thought are just getting started. I doubt that everything will be excavated, or the ancient story fully told, in this life. But if you have any interest in such things at all, it’s amazing to think of all the wealth of all those tells sitting there with their meters and meters of secrets.

Exquisite.