This painting is me in twenty years. I hope. Note my cottage in the background.

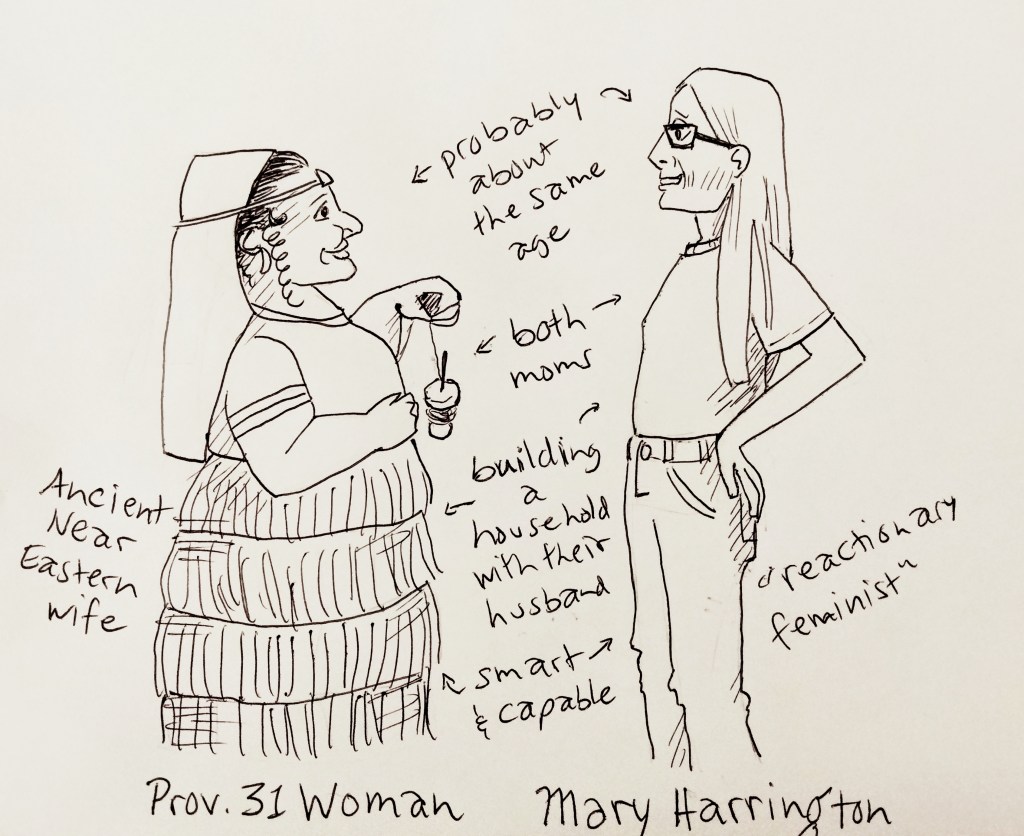

Our Friend Mary Harrington

I want to talk about another lovely gift that I have been given by reactionary feminist author Mary Harrington. I reviewed her book, Feminism Against Progress, here.

In the video below, Jordan Peterson interviews Harrington. She gets to talk a lot. I don’t know whether this is because Peterson is mending his monologuing ways, or because Harrington is confident, articulate, and not afraid to take long turns, but in any case, we definitely get to hear her thoughts. They are not the exact same thoughts as the ones she expressed in Feminism Against Progress. You can see that her thinking is still developing, particularly the terms she likes to use to describe things.

It’s a very long video, and well worth the listen if this topic interests you, but for your reading pleasure I have transcribed the section that I want to talk about. Here it is:

At about 46:24, Peterson says, “The thing about women is that their mythological orientation is multidimensional and complex.” He mentions Beauty and the Beast, and Woman and Infant, as two possible hero myths for women, but notes that “our society does not hold sacred the image of Woman and Infant as a fundamental unit of female identity” (so we’re really only left with Beauty and Beast, which gets us into trouble).

Then at about 49:00 he asks Harrington, without asking a direct question, what she thinks is the woman’s Heroic Journey. And she’s got an answer for him!

After a detour into why she felt lonely as a young mother, Harrington answers at 51:45,

“In my observation, there is a hero’s journey for women, it just doesn’t follow the same track as the male one. And in fact, it has three parts, which correspond to a very ancient female archetype, which is the Maiden, the Mother, and the Matriarch. The triple goddess. And anecdotally, it stacks pretty closely to me with actually what a majority of normal women’s lives look like.

“You know, as the Maiden, you’re free, you do have more of a warrior aspect. The Mother is more oriented towards home and the domestic sphere, and probably bluntly just doesn’t care about [outside] work as much.

“But then, later on – and this was something I found very interesting when I did therapy training in the late aughts and early tens, was just how many of the trainees on that course were women in their 50s and 60s. So these were women who had pretty much done the motherhood arc, and they were moving into a new phase of life. They were moving into the Matriarch space. I mean the classic, three-part-goddess term for this is Crone. But they were some way from cronehood. These were lively, vital, energetic, public-spirited women who had some life experience. They had a lot of connections, they had a rich social life, they had met lots of people, and they were ready to give something back.

“And in my observation, there are a huge number of women who reach the end of the Mother part of that journey, and will then re-train. And those women are a huge, rich force for deepening reflection in the culture, for public service, for all manner of incredibly productive, usually quite self-effacing, but incredibly productive, life-giving contributions to the social fabric. And they’re incredibly marginalized. They’re almost completely invisible in terms of the liberal feminist narrative, which really centers the Maiden. And it wants to foreground the Maiden and to tell women that the hero’s journey means essentially being the Maiden for their entire life. At best, if the Mother is noticed, it’s as a problem to be solved. And the Matriarch doesn’t really get a look-in at all, and if she does, it’s only so that she can be denounced for being a TERF, or in some other way spat on for being a dinosaur or obsolete or old-fashioned or out of touch, or in some other way irrelevant or ridiculous.

“And in fact, these [older] women are the backbone of the social fabric. I mean, those are the women who are making weak cups of tea for slightly traumatized new mothers like I was in small-town England. (laughs) And telling me I’m doing fine. And really, that mattered a lot at the time. I mean, those are the women who are running Brownies groups for no money every Wednesday because they can and because they want to give back. Those are the women who are re-training as counselors and helping traumatized people for free. Those are the women who keep things going. (laughs again) And yet, somehow, the liberal feminist version of the hero’s journey just doesn’t see them at all.”

About that word “Crone”

I love what Harrington has to say here. But I must make a note of how she shies away from the word “crone” in favor “matriarch.” Based on the qualifications she puts around even mentioning the word, it’s apparent that Harrington thinks crones are women at the very end of their lives, who are listless and isolated: the opposite of “having a lot of energy” and “lots of connections” and “a rich social life.” The word crone in Harrington’s mind apparently conjures up a bedridden hospice patient who enjoys her only social interaction when the pastor visits once a month.

I got a similar reaction out of my editor when I went to describe Zillah (one of the main characters of my trilogy) as a crone. The word crone, said Editor, reads “old and ugly.” I convinced her to leave it, because I wanted to broaden the meaning of the word, or perhaps recover some of its original meaning.

Zillah, in my series, is in her sixties when we meet her in The Long Guest. I’m cheating a little with having a protagonist in her 60s, however, because my books are set in the immediate post-Flood era, when people lived into their 250s, and a woman in her sixties could still be fertile. Zillah has grown children in The Long Guest, but she still looks like a young woman, and in fact she gets her own romance arc.

In later books, Zillah gets older. By The Great Snake, when I was calling her a crone, she was over one hundred. By the standards of the time, this is only middle-aged, and in fact she is strong enough to hike all day, do dryland farming, and so forth. However, her role in the community is definitely what Harrington describes above as Matriarch. She practices emergency medicine and herbology, innovates in farming maize, counsels her family through crises, and brings potential problems to the attention of the patriarch (who is not her husband but her son). She can’t do everything, and in fact she has had some costly failures. But my trilogy would be much darker without Zillah.

I’m not saying my books anticipated what Harrington is saying, but … my books anticipated what Harrington is saying.

Hats off to Grandma! Or are they?

Of course, she is not the only one saying it (though she may be saying it the most eloquently, and with the biggest platform), and she is not the only one thinking it. Every woman is thinking through these things, whether she realizes it or not, and most women come to some kind of resolution. You have to, if you don’t want to live your life with a pathological fear of aging. This is not an attractive look, and most people figure this out and make some kind of effort to “age gracefully,” that is, to embrace their status as an older person.

This task is made more difficult in modern Western society, where we as a culture don’t value our elders at all and don’t really have any special role for them in the community. This is true of old men, to a lesser degree, but it’s really true of old women. Has anyone heard the phrase, “old women of both sexes”? It’s usually used in the following context: “I want to do bold plan XYZ, but when I said so, it really upset the old women of both sexes.” Old women, we learn, are fragile, risk-averse, set in their ways, and prudish. Probably bureaucrats. Also, they are not athletic or healthy (two other things our culture really values).

Our culture’s disdain for old women traces back to its disdained for motherhood and family life. If you don’t value mothers as such, then you are less disposed to respect your own mother when she is old. Further, if a culture does not have a lot of young moms who need help at home, then there really is no job for the old ladies to do other than go to work in an office, where the hours, tasks, and working conditions are often uncongenial to their nature and where admin would really like to push them out before they develop a bunch of expensive health problems.

On the other hand, if your culture prioritizes a large, thriving household of the kind described in Feminism Against Progress and in Proverbs 31, then there is plenty of useful work for Grandma to do. Furthermore, it’s exactly the kind of work she has spent decades becoming good at. She’s baking her famous dessert, she’s sewing outfits for the little kids, she’s quilting, she is babysitting. She’s answering Mom’s panicked questions about how to garden, get that stain out, and how in the world do I manage everything. This is work that is actually useful and needed (which is the kind of work that keeps people alive and happy). But it’s not like going to work in a shop or office in your fifties. There is more variety, and the schedule is freer. There is room for Grandma to go home and be by herself for a few days. There is room for her to take a nap. And unlike admin at the office, your grown children will not fire you and wash their hands of you when you develop health problems (not ideally, anyway).

Of course, all this is the ideal, and we all know that reality is different. Not every family relationship is a happy one that would allow this kind of close community (especially 60 years after the Sexual Revolution began its relentless campaign to break up families). And even in ideal circumstances, we can get on each other’s nerves. That’s why, in the painting, I am living in a cottage in the woods, where I can garden, paint, and keep a library. Ya gotta’ know your limits. But there is a world of difference between having some tension with your children in a context that values and honors older people for their wisdom and experience, and having to get a 9 to 5 job that really calls for a younger person, just to prove you’ve still “got it” and to justify your existence. This is the difference between Zillah’s world and ours.

Looking forward to being a Crone

I have been fortunate that I was a given a husband and children. I’ve moved through the stages and am now standing on the threshold of matriarchy/cronehood. And I’m liking the view.

Don’t get me wrong … I’m frightened as well. What scares me most is the prospect of chronic pain or disability — my own, or a loved one’s. But I’m not scared of aging itself. I like the idea of less pressure to look beautiful, of a lightening of parenting responsibilities (in exchange for others), and of time to keep getting better at my various crafts.

As a Christian, I am surrounded by a world that despises motherhood, families, and old women … but I have access to a world that honors them. I am in the world but not of it.

Also, I realize that I need to do a better job appreciating the older women who have surrounded me since I was small, my own mother included. I didn’t ever like being taught new things, because of the amount of correction it involved, but now I see how much we must listen to these ladies, honor them, eat the food they cook for us. Send in the crones!