Everyone here [in the pub] has stuff to tell him and ask him, and stuff they want to tell each other about him. Not a one of these things will be said in so many words; lack of clarity is this place’s go-to, a kind of all-purpose multi-tool comprising both offensive and defensive weapons as well as broad-spectrum precautionary measures.

Tana French, The Hunter, p. 350

Tag: MBTI

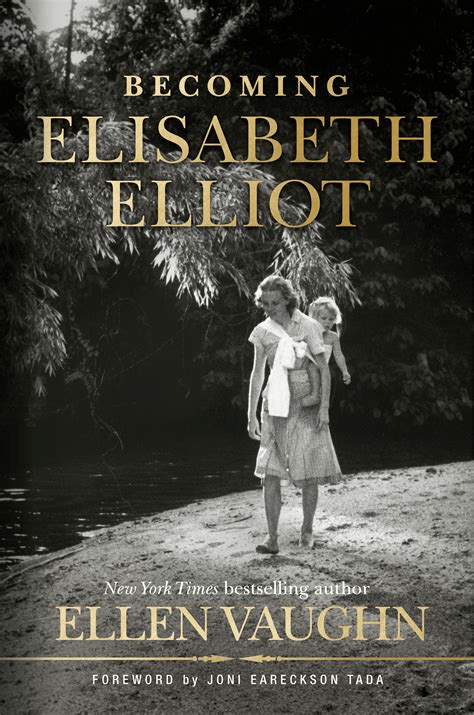

Becoming, and then Being, Elisabeth Elliot: a review

Quick! Who do we know who’s a linguist, a former missionary, a gifted writer, and wants to capture in novel form the human condition and God’s grace to us in it?

Who is awkward, reserved, and can come off as rude and abrupt, but actually has passionate emotions, a deep love for others, and a rich inner life?

Who loves nature? Crosses cultures happily, but doesn’t fit in so well in the American evangelical context? Who has a secret desire to be admired, but also suffers from poor judgement about the opposite sex?

Why, Elisabeth Elliot, of course!

Me and Elisabeth Elliot

When I was college and just discovering the things I ranted about last Friday, like the fact that we as a culture could use some guidelines about the how the sexes ought to relate to each other, I came across Elisabeth Elliot’s book Passion and Purity. I devoured it.

This book was exactly suited for me at the time. I was just starting to grow in Christ. I really wanted to do God’s will. I also, unbeknownst to me, had a lot in the common with the author of Passion and Purity: socially awkward, ascetic tendencies, perfectionistic, a longing for old-fashioned values. This book is basically about the lessons Betty, as she was called at that time, learned during her five years (!) of waiting for Jim Elliot to make up his mind that God had given him the go-ahead to marry her. Their courtship story strikes many Christian young people as really spiritual upon first hearing, and then on a second look, it starts to look as if he didn’t treat her very well possibly. But I bought into it fully.

Anyway. Full of missionary zeal to win other young people over to the idea of an extremely awkward, chaste, long courtship, I gave this book to a friend. She read it, and her reaction was, “There are the Elisabeth Elliots of this world, but I am not one of them.”

That annoyed me at the time (someone had rejected my idealistic ideal!), but from my perspective now, that friend of mine didn’t know how right she was. In fact, not even Elisabeth Elliot herself was one of the Elisabeth Elliots of the world, at least not in the sense of having perfect wisdom and self-control. At the time she was writing this (early 1980s), Elisabeth was enduring an extremely controlling marriage with a man she married because she didn’t want to be lonely. She stayed with him for the rest of her life, despite an intervention by her family. It’s chilling to realize that the woman who wrote Passion and Purity could make such a foolish decision.

Before Passion and Purity, I remember as kid seeing black-and-white photos of Elisabeth toting her small daughter Valerie into the jungle to serve the Waorani people (then called the Auca), a few years after her husband Jim was killed by them. These were the photos taken by Hungarian photographer Cornell Capa. They, and the books Elisabeth wrote about the Waorani, had made her and her martyred husband Jim famous throughout the evangelical world.

Both greater and lesser than I thought

When you think you know a story, you expect it to be boring. I put off for some time reading this duology by Ellen Vaughn, until it finally floated to the top of my reading list. Once I opened the books, I found that I couldn’t put them down. Vaughn is an excellent researcher and a vivid and sympathetic writer, and though I had read a number of books by and about the Elliots, I certainly didn’t know as much of their story as I thought.

Vaughn, aware that she is telling a story the outlines of which are familiar to readers, moves skillfully back and forth through time, as in a novel (though in rough outline, the first book deals with Betty’s early life and the second book with her post-Ecuador years). Vaughn doesn’t try to tell every story–there are too many, many of which have been told elsewhere, and others of which are apparently too private and will stay hidden forever in Elisabeth’s prolific journals. In fact, as I read these books, I felt I was getting to know two fellow woman writers: Elliot and Vaughn.

When you are a former missionary, it’s difficult to read other missionaries’ stories without comparing them to your own. Usually, this means you are reading about people who were far ahead of you in dedication, selflessness, toughness, and in what they suffered. This is certainly true of the Elliots. At the same time, so much of their personalities and stories seemed shockingly familiar. For example, young Jim Elliot was, besides being a great guy, an insufferable holier-than-thou know-it-all, of the “I’m going to go read my Bible” type. Betty, as Elisabeth was then called, was quiet and reserved and often didn’t realize that she was coming off as standoffish. Jim’s family verbally eviscerated her after her first visit to their home in Portland, and foolish young Jim passed all these criticisms on to Betty in a letter. She was devasted, but thought and prayed over the things they had said, and then concluded that none of them were things she could actually change. Later, Jim couldn’t believe he had shared his family’s words with Betty. As Bugs Bunny would say, “What a maroon. What an imBAYsill.”

They were just people, you see. Not angels. Which means that “just people” can always serve God.

Jim Elliot, you beautiful dunce.

The things they suffered also rang poignantly familiar. They suffered setbacks that lost them a year of their work–for her, language work; for him, building a mission station. Neat and tidy Elisabeth at some points had to live in squalor, and felt guilty for the fact that it bothered her. Fellow missionaries (not all) and Waorani Christians alike (not all) proved manipulative and controlling. In fact, it was relationship difficulties that caused Elisabeth eventually to leave the Waorani, after spending only a few years with them. This was not Elisbeth’s fault: person after person found it impossible to work with Rachel Saint, her fellow translator. But she took on as much of the responsibility for it as she possibly could, agonizing before God in her journals, because that was the kind of person she was.

Elisabeth the Novelist

Now we are getting into events of the second book, Being Elisabeth Elliot. Elisabeth knew that she had a gift of writing. She had made so much money from her books Through Gates of Splendor and The Shadow of the Almighty that she was able to build a house for herself and her daughter near the White Mountains of New Hampshire (talk about living the dream!) and settled down to become a writer. She really wanted to write great literature, the kind that would elevate people’s hearts and give them fresh eyes to see the great work of God all around them in the world.

If I were writing a novel about Elisabeth Elliot, I would end it there, and let her have a period of rest, in the beautiful mountains, with her daughter, writing her books, for the rest of her days. I wish that was how it had gone. I kept hoping, as I read this duology, for there to come a point when Vaughn could write, “And then, she rested.” Alas, that moment never came.

Elliot was indeed a really good writer. Sometime in the twenty-teens, when I was a young mom who had come back from the mission field hanging my head over my many failures, and had unpacked my books and settled into a rented house to minister to my small children, I found on an upstairs shelf a slim volume that looked as if it had been published in the 1960s or 70s, called No Graven Image. This was the novel that Elliot wrote when she first settled down in New Hampshire. She wished, through fiction, to give her readers a more powerful, truer picture of missionary life than her biographies had done.

This is not the cover my copy of the book had, though it also had an image of a condor.

No Graven Image was not well received when it came out. It was the old problem of marketing. To what audience do you market a genre-bending book? The people who liked to read tragic, worldly novels were not interested in a so-called “novel” about a young missionary woman, probably expecting that it would be preachy. The Christians who liked to read missionary stories were shocked and dismayed by a novel in which the protagonist flounders around, makes mistakes, and ultimately, accidently kills her language informant when he has a bad reaction to a shot of penicillin. And then decides that her desire to have a successful language project had been a form of idolatry.

Some readers appreciated the novel (particularly overseas missionaries), but most found it shocking, even blasphemous. They wanted a triumphant novel, not the story of Job. They wondered whether Elisabeth had lost her faith.

When I picked it up, in the twenty-teens, it made me feel extremely understood.

One thing that killed me as I read of Elisabeth’s later years is that this was the only novel she wrote. She very much wanted to write others, and she got as far as making notes for another novel. But life (read: men) intervened, and she was in demand for speaking and for writing nonfiction books such as Passion and Purity. She wasn’t able ever again to get the extended periods of time to concentrate that it would have taken to gestate a novel. She convinced herself that she just didn’t have what it took to write actual good fiction (and perhaps, that it was selfish to try). I am so sad to watch this dream die. I believe that she would have been a good novelist. I don’t know whether her publisher would have kept publishing her books if she had turned to fiction, or whether she would have had trouble finding another publisher. Spiritual non-fiction was what she had already become known for. She probably would have made less money, perhaps found it difficult to support herself. But still … you know … it’s hard to watch. So many things about the second volume of her biography are hard to watch. At the same time, because of Vaugh’s amazing research and writing, it’s hard not to sit back and just stare at this major accomplishment.

PUNS! Brought to you by the ENFP

Time for another Meyers-Briggs profile.

The ENFP

This abbreviation stands for Extraverted, INtuitive (grasping things with a quick impression instead of looking at every detail), Feeling, and Perceiving (going with the flow instead of planning a lot).

According to the website 16personalities.com:

When something sparks their imagination, ENFPs show an enthusiasm that is nothing short of infectious. These personalities can’t help but to radiate a positive energy that draws other people in. Consequently, they might find themselves being held up by their peers as a leader or guru. However, once their initial bloom of inspiration wears off, ENFPs can struggle with self-discipline and consistency, losing steam on projects that once meant so much to them.

Even in moments of fun, ENFPs want to connect emotionally with others. Few things matter more to these personalities than having genuine, heartfelt conversations with the people they cherish. …

ENFPs need to be careful, however. Their intuition may lead them to read far too much into other people’s actions and behaviors. Instead of simply asking for an explanation, they may end up puzzling over someone else’s desires or intentions.

My Particular ENFP

As it happens, I am married to an ENFP, so I can tell you all about them. I can say with confidence that anything done by my ENFP is, reliably, done by every other ENFP out there. You can rely on me for guidance to this type.

And what I can tell you is that ENFPs make puns.

Puns are my ENFP’s daily bread. When he gets on a roll, he makes them a-grain and a-grain. They are a lot butter than these ones I am making, dough.

Few things are a bigger treat than to have a front-row seat when an ENFP and another type that likes to pun get into a pun volley. I have been witness to a few of these, where they not only stayed on the facial topic, but also kept the puns within the same theme. This kind of art is so ephemeral, I have forgotten all the puns they made.

ENFPs are funny with language. They might have favorite big words:

- Chick flicks are films that are lugubrious. I don’t like getting all lugubrious.

They tend to give things funny names. See if you recognize these restaurants:

- Burger Death

- Dead Lobster

- Taco Gehenna

- Taco Jaundice

- Unterweg

- Little Squeezer’s

- Dead Robin

Other nicknames are not suitable for a public blog.

Speaking of which, ENFPs (again, this is based on my extensive expertise) are so into building good relationships that will use mock attacks to do so. For example, my ENFP has occasionally been known to cry out, “Lies!” while a friend is speaking. He once asked me whether I thought he ought to sucker-punch another guy in the lobby at church, because they were friends. (He ended up faking a punch.) Often, these play fights become in-jokes, another category of relationship/humor that the ENFP loves. Once something has a silly nickname, or someone has been accused of something ridiculous, it stays that way forever, or at least until a better in-joke comes up.

My ENFP loves insults that sound unanswerable, for example:

- If we aren’t supposed to eat animals, how come they are made of meat?

- If you have a little more time, I have a few more pearls to cast.

Neither of these is original to him, but he uses them frequently.

But as a counterpoint to all the linguistic virtuosity, you get utterances like this:

- Did you load the one thing? (the dishwasher)

- Have you seen that one kid? (that’s your son, sir)

- We need to get the thingy. (You got me on this one. The taxes? The lotto ticket? Another chicken coop? I don’t know, but it’s urgent.)

ENFPs are the type most likely to use words like whatsit, thingamagig, dealybob, and doohickey. They are very smart, but they can’t always slow down to locate the precise term. In Southeast Asia, we learned the term ano, which can literally replace any part of speech. My ENFP still uses it occasionally.

ENFP’s gifts make him the perfect trip planner. He is great at throwing together a spontaneous weekend jaunt to go on a hike or see a local (or not-so-local) site … and get eight people to join him. And he will be punning all the way.

Keepin’ Everyone in Line: the ESTJ

Here it is: my next post about one of the sixteen MBTI types! I’ve already profiled ESTP and INFP, from my unique, rather personal perspective. (INFP is me — and Frodo –, and ESTP is the antihero of my first novel, so he has a special place in my heart, even though he would drive me CRAZY in real life.)

If you don’t like the MBTI, please skip this post. I’ve already shared my caveats about it, and noted that the same territory is covered, just as effectively and probably more data-based, by The Big Five. However, I still enjoy the MBTI, and if the Lord wills, I will eventually make a post about every one of the sixteen types. I just don’t think it should be woodenly applied. It’s descriptive, not prescriptive.

The ESTJ

ESTJs are people who are Extraverted and prefer Sensing (they build up from sense data rather than getting an intuitive big picture in one fell swoop), Thinking (they aren’t overly concerned with their own or others’ feelings when making decisions), and Judging (they like to organize their time and environment rather than going with the flow).

According to the website sixteen personalities,

ESTJs are classic images of the model citizen: they help their neighbors, uphold the law, and try to make sure that everyone participates in the communities and organizations that they hold so dear.

Strong believers in the rule of law and authority that must be earned, ESTJ personalities lead by example, demonstrating dedication and purposeful honesty and an utter rejection of laziness and cheating. If anyone declares hard, manual work to be an excellent way to build character, it’s ESTJs.

This is the type that loves to play games (Monopoly, Uno) because they can remind everyone of the rules … and maybe even make up some rules, too!

I have an ESTJ

Being as it is the opposite of my personality type, perhaps God knew that I would not learn to love ESTJs unless I gave birth to one.

It started from the womb. My ESTJ baby wasn’t comin’ out until he was good and ready. We went to the hospital three times with false alarms, which left us embarrassed and worried about the cost. Finally, when I did really go into labor, we stalled out and got sent home again. But finally, some time the next day, we had our precious little ESTJ. (Also, by the way, I had a very quick labor with my first, but a more normal length of labor with my ESTJ. Remember, they like to do things in the way that is socially acceptable.)

It’s hard to be an ESTJ when you are little and don’t have anyone to direct or keep in line yet. This is the kid that you are always having to remind, “You are not the parent.”

However, when they get older, the ESTJ’s unique gifts start to shine. My son’s coaches love him, because he follows instructions and always practices and plays with all his heart. (Remember, ESTJs are model citizens.) As a Judging type, he is super organized and always lets me know about upcoming events, fees and assignments due, and so forth. On the whole, this is a lovely type and society needs a lot of them. They are almost 9% of the population according to estimates, but since this is a type that is likely to be involved in social institutions (and getting others involved), they may be setting expectations out of proportion to their number. They may be unpleasantly surprised when weirdo types like myself can’t just easily get with the program.

Things my ESTJ has said

- “Do it!” (He used to say this a lot at the age of about two. It is quintessential ESTJ.)

- “C’mon, Spidey, let’s go up to the Celestial City.” (This is one of my favorite quotes from him.)

- “[The guy opposite me in the football game] got mad ’cause I was doing my job.”

- “Why are you such a libertarian? What’s a libertarian?” (He’ll often accuse me of being a new word in order to find out what it means.)

- “I don’t have a personality. I just do what makes sense.”

ESTP Quote of the Week

Except for learning things, Otis liked school. He could find so many ways to stir up excitement.

-Otis Spofford, by Beverly Cleary, pub. 1953

A Poem Composed Before 7 a.m.

The upper I get,

the earlier I’m.

The House of Love and Death: A Book Review

I ordered this and it arrived a long time ago, but I just now got to it. (Look at me! I am powering through my TBR like a good girl!) Once I opened it, I finished in just a few days because it’s that good.

This is the third book in the Cameron Winter series. Winter is a character created by Andrew Klavan, reportedly the first character Klavan has created that he’s felt could sustain a whole series. Winter is a former spy who is now a professor of Romantic English Literature at an unnamed university in an unnamed Great Lake state (but pretty obviously Madison, Wisconsin). So he fits into that beloved mystery trope, a character who looks unprepossessing (in this case, because he’s a slight, blond, pretty-boy academic) and whom people consequently underestimate, unaware of his hand-to-hand combat skills.

It was fortuitous that I read House not too long after reading The Bourne Treachery, which is also a spy story featuring a longstanding character. Winter even has, in this book, some experiences similar to those Bourne has in Treachery. However, the two books couldn’t be more different.

Winter does check many of the same boxes as Bourne, and House checks many of the same action-novel boxes as Treachery. It moves a little slower and is a little less intricate, but not much. But it is way more emotional. This is one of those mysteries where, after you find out whodunit, you have to set the book down and (if you are a soft touch) cry for a while as you contemplate just how tragic the whole thing was. And like any good tragedy, it has the simultaneous feel of “This was so preventable! This should have been easily preventable!” and of inescapability.

Winter has a “strange habit of mind” (also the title of the first book in the series), where sometimes he will go into a “fugue state” and zone out for several minutes while his subconscious, essentially, becomes his conscious and works on a puzzle he is contemplating. As a writer and artist, I recognize this habit of mind and actually don’t find it that strange (although it doesn’t help me solve mysteries, more’s the pity). I assume that Klavan has given Winter this “strange habit” because, as an artist and writer, he also has some version of this habit. Certain kinds of mind tend to do this. Call it what you want – hyperfocus, being “in the zone.” Being an introvert. Not everyone is “on” (in the sense of externally focused) all the time.

It does make a person wonder whether this tendency, which is similar to narcolepsy, disadvantaged Winter as a spy. In fact, it makes one wonder how he ever managed to survive his espionage years. If Jason Bourne were to zone out like that even for a minute, he’d be dead. Once in House, Winter is driving somewhere and keeping an eye out for a tail. He briefly enters the fugue state, and when he comes out of it, sure enough, he is now being followed.

Yet somehow, those of us with the strange habit of mind do manage to survive. Some of us even manage to raise children. I dunno.

Anyway (shakes shoulders) aaahh, good book. Recommend. Very very sad though.

The Eloquence vs. Coherence Alignment Chart

This was inspired by me leaving comments in a feverish state, and realizing that such a chart probably existed and I was in the wrong quadrant possibly. Characteristically, when I made the chart I forgot to put “fever” on it, but clearly “I have a fever” would go in the upper left quadrant, which is by far the fullest.

I hasten to point out that this is all in fun. Except for the dig at Karl Marx.

That Time John Calvin Got Guilted into Moving to Geneva

There was a detour sign on [Calvin’s] road from Paris to Strasbourg. Francis I and Charles V were in the opening stages of their third major war. Armies sprawled across the roads forbade passage. Calvin bent his way southward by Geneva … He went to an inn, planning to spend one restful night and be gone. But … there was knock on the door of Calvin’s chamber, and an importunate caller entered, who felt himself commissioned to remake the scholar into a leader. This was, of course, Guillaume Farel, the venturesome, big-voiced, red-haired little evangelist and controversialist … Farel and his associates were intent on reconstruction [in Geneva] and had taken some significant steps in the ordering of discipline, worship, and education. [W]hen [he found out] that Calvin had come for the night, Farel eagerly sought him out, resolved in to enlist him in the Geneva work.

The interview was both dramatic and historically momentous. Farel was twenty years Calvin’s senior, and a man of flaming zeal. Calvin longed for the library and the study; to Farel this would be a desertion of the cause of the Lord.

“If you refuse,” he thundered, “to devote yourself with us to the work … God will condemn you.”

Calvin later testified that he had been terrified and shaken by Farel’s dreadful adjuration, and had felt as if God from on high had laid His hand upon him.

John T. McNeill, The History and Character of Calvinism, pp. 131 – 136

Happy New Year! Don’t let anybody guilt you into any historically significant moves!

Another, Sort of Interesting, Personality Typology Book

I saw this at my local library.

I like reading personality typology books — as long as they aren’t too dumb — because I’m interested in stories and people. And people within stories. I am aware of the limitations of personality typologies. I don’t think I’ve ever seen one that can capture all the nuances of a person; and, in fact, it would be surprising if we could. I have a made a few previous posts about the MBTI, but I know that it has been criticized and has been woodenly applied in a business context.

The MBTI yields sixteen basic types, and even it is not perfect. So of course, any typology that only has four types is going to be even less of a fit, unless you apply it generously and with some fluidity. (Which is different from making your typing of people unfalsifiable by always having an explanation for features that contradict your theory.) Carol Tuttle’s typology is a four-typer. Her four types correspond roughly to the ancient four types of Sanguine, Choleric, Phlegmatic, and Melancholic.

The book is somewhat woo-woo. (And whoo boy — I mean, hoo boy, her web site is even more woo-woo!) The way Tuttle explains her philosophy is that there are four types of energy present in nature, and while all people use all of these four types, each of us “expresses” one of the types of energy in particular. When she writes about people who have attended her seminars, she tends to describe them as “a woman who expresses Type 3 energy” instead of saying “a woman who is a Type 3.” I feel like there’s wisdom in that. Other woo-woo aspects: she explains how each type handles its energy in terms of yin and yang, and in the profiles of each type, she even includes a description of physical features that people with that sort of energy are likely to have. It was the physical descriptions that lost me. That seems like way too much of a claim. I have a much easier time accepting a typology that is just based on the way you approach life and the effect you have on other people, not just with things you explicitly do, but with the energy you bring into a room (about which more in a minute).

And yes, people do attend her seminars. Each chapter in this book has testimonials from people whose lives were improved once they were able to recognize and accept their type.

And yes, she did name the Types 1, 2, 3, and 4, which I think shows admirable restraint. Here they are:

- Energy that is light, lively, cheerful, and vertical, like the movement of an aspen tree.

- Energy that is smooth and down-ward flowing, like the Mississippi River.

- Energy that explodes outward, getting things done, like the sun or the appearance of the Grand Canyon.

- Energy that is constant, still and stable, like a rugged mountain reflected in a glassy lake.

(Notice: Air, Water, Fire, Earth.)

One thing that caused me to actually read this book (and then even go so far as to review it!) was that, as soon as I started skimming it, I began recognizing family members in the descriptions. One of my children, for example, clearly has Type 1 energy, and even loves rabbits, which because they move by hopping are cited as a Type 1 sort of animal.

Of course, not everything applies perfectly. Not everything said about Type 2 express-ers is true of me, for example. (No, I am not diplomatic nor am I good with numbers.) And some people don’t immediately seem to embody these types. So, despite the testimonials, I am recommending this book as an item of interest, not as something that is going to change your life.

What it really teaches you is how to dress.

Apparently, Tuttle has an entire seminar called “Dress Your Type.” The idea is that, when you dress in a way that matches the type of energy you bring, people know what to expect from you and they are more likely to respond to you in a way that’s in keeping with your general approach to life. I am all in favor of letting people know what to expect. I relied heavily on this principle when naming my children, for example.

Tuttle recommends that only people with Type 4 energy wear black. These people tend to be striking and somewhat forbidding in their aspect, and serious in their approach. Other types, she says, will be made to look tired or older by black. I’m not sure I’m ready to give it up, but OK.

Her approach does explain an awful lot about my sartorial preferences. I love flowy things: long belts, fringes, shawls, ponchos, bell sleeves, long hair, medieval historical dress, and all of these things are totally impractical for everyday work around the house, but apparently they express my flowy, Type 2 energy, so you have been forewarned. (I also write long, rambling novels.)

According to Tuttle, Type 2 is “a double yin” whereas Type 3 is “a double yang,” which might explain the following story.

My husband and I had just come through an extremely stressful period at work. We then had to travel for some meetings. The site where we were staying was sort of a vacation site, but it was a working trip too. We were trying to do a good job in the meetings, but also sort of relax and process all the stress we’d just been through. It was also a place where many people were coming and going, including a very energetic gentleman whom we had first met about a month earlier. This guy was one of those types who do an amazing job at their own role, and also insist that “everyone can do it!”

I was supposed to be taking notes at the meetings, but one morning, I woke up feeling awful. I dragged myself down to the kitchenette area and was just trying to force down some breakfast, hoping it would make me feel better, when the door burst open and in rushed Type 3 Energy Man. He didn’t even speak to me, but his presence was all it took. I dashed outside and threw up in the flower bed.