Near Bayou Macon, Louisiana, is an archaeological site called Poverty Point. I am drawing for information about Poverty Point primarily on the book Mysteries of the Ancient Americas, 1986, by the The Reader’s Digest Association Inc., but here is the official Poverty Point web site. It is now a World Heritage Site. Here is a recent article about an archaeological project done at Poverty Point.

First, the Obligatory Eye-Rolling at Mainstream Archaeology

Like many North American sites, Poverty Point was hard to spot because it consists of earthworks that had been overgrown with forest. (And not only North American sites. Radar technology is revealing that the Mayan civilization was much more extensive than first thought — because the jungle took over so quickly — and is also revealing old settlements in what was hitherto thought to be never-before-settled Amazon rainforest.)

Earthworks are basically impossible to date, but for other reasons, Poverty Point is thought to be about 3,000 years old (i.e. about 1,000 B.C.). However, it helps to remember that when dealing with paleontology and even archaeology, dates are often basically just made up — i.e. reached through dead reckoning based on a shaky framework of background assumptions. But let’s accept 1,000 B.C. for now.

Mysteries, which again, was published in 1986, also makes several more or less dubious claims about the builders of Poverty Point. Here’s a sampling:

“[S]cholars think it is doubtful that societies on the chiefdom level existed in North America 3,000 years ago.” (page 111)

“[This civilization] had no writing, no true agriculture, and no architecture except for its earthworks. Its weapons were simple: the spear, the atlatl, the dart, the knife, and possibly the bola. Even the bow and arrow was unknown to these people.” (page 112)

“Considering the massiveness of Poverty Point’s ridges and mounds, one naturally assumes that they were built over many generations or even centuries.” (page 112)

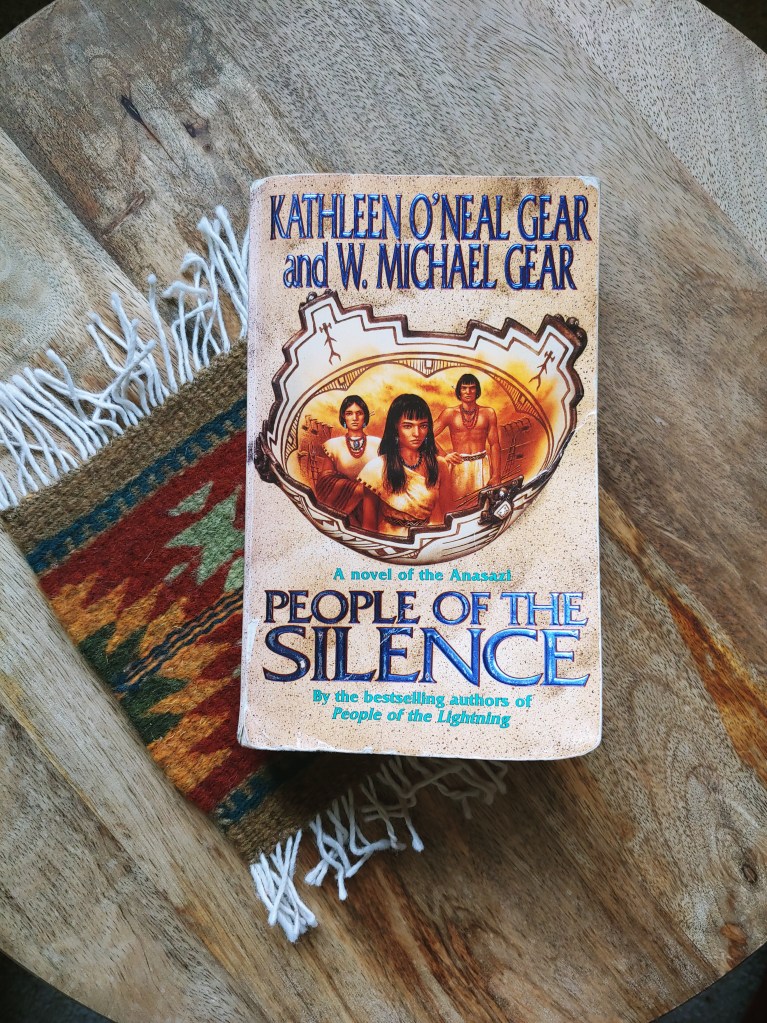

Mysteries of the Ancient Americas

The first of these quotes is 100% pure assumption, based on the noble savage mythology so beloved of modern academics.

The second is also pure assumption. A better way to put it would be that we have found no evidence of writing, agriculture, etc., so far. The findings reported at the first link above seem to confirm that agriculture was not a big thing at Poverty Point, based on the remains of the peoples’ diet, but this could have been simply because the fishing and foraging was so abundant. It does not necessarily mean they were “only hunter-gatherers” who had not “advanced” to the level of agriculture. C.f. similar claims being made about Gobekli Tepe. As for the bow and arrow, I take it that remnants of all these other weapons have been found, but not bows. Even that, I take with a grain of salt, as it seems that almost every week, something is discovered that we had thought this or that ancient group didn’t have. (Here’s the latest example, which even refers to ancient humans as not particularly ‘smart,’ with ‘smart’ in scare quotes.) But even if the Poverty Point people did not use bows and arrows, this does not necessarily mean the weapon was “unknown” to them. Perhaps they had specialized in other weapons instead. Not everybody in the Middle Ages was an English longbowman, but boy oh boy did they know about them!

Finally, the third claim made in the Mysteries quote box (which they at least had the grace to call an assumption), appears to have been possibly disproven by the second link above. “New radiocarbon dating, microscopic analysis of soil, and magnetic measurements of soils at Ridge West 3 found no evidence of weathering between layers of soil, suggesting that the earthwork had been built rapidly.”

Now, the Site Itself

It’s easier to just show you guys this diagram than to try to describe it, but buckle up, here comes the description. The Poverty Point site consists of earthen ridges set concentrically inside each other, in what looks like a C-shape from the air. “The two central aisles point toward the setting sun at solstice” (ibid). Directly to the west of all this is a large man-made mound (Mound A), while a ways farther north there is a smaller mound (Mound B), which seems to be a burial mound. Bayou Macon, directly to the east, cuts through the eastern side of this whole complex. Was this whole thing originally C-shaped, or was it a circle? Probably a C shape, because there are similar, smaller sites around this region which tend to be “constructed in a semicircle or semioval pattern with the open side facing the water and with one or more mounds located nearby.” (ibid)

The book uses the word “ceremonial” a lot, and honestly I can’t fault them. This complex was constructed by human beings, and now, millennia (?) later, more human beings come and look at it and say, “This looks like it was clearly designed for ceremonial purposes.” That’s a valid argument. The architecture is having a certain effect on us, and we can assume that it had that same effect on our long-lost fellows, and was designed to.

Poverty-Point-related sites have yielded thousands of little decorated clay balls, called Poverty Point objects, that we think were used for cooking. There are also little clay sculptures of female torsos (with or without heads), reminiscent of the Venuses found around ancient Europe. There are also “myriads of stone tools,” including drills, awls, and needles, made both from local stone and from flint imported from as far away as Indiana. They made “plummets,” perhaps as bola weights or perhaps as weights for fishnets, “most often of hematite in graceful teardrop or oval shapes [and] often decorated with beautifully executed stylized designs representing serpents, owls, and human figures.” (ibid, p. 115)

But it is in lapidary work that the Poverty Point people excelled. Pendants, buttons, beads, and small tablets are worked in an array of such colored or translucent stones as red jasper, amethyst, feldspar, red and green talc, galena, quartz, and limonite. Most of these stones were obtained by far-flung trade. Among the pendants are a number of bird effigies — red jasper owls and parakeets, and bird heads worked in polished jasper and brown and black stones. There are also representations of a human face, a turtle, claws, and rattles, and stubby but carefully made tubular pipes.

Mysteries of the Ancient Americas, p. 115

O.K., I’ve changed my mind. Perhaps this C-shaped complex was not ceremonial, it was a lapidary factory.

Regardless, the Poverty Point “hunter-gatherers” have once again made my point for me: that wherever human beings go, they start up civilization and display mathematics, art, and craftsmanship.

The Snake City

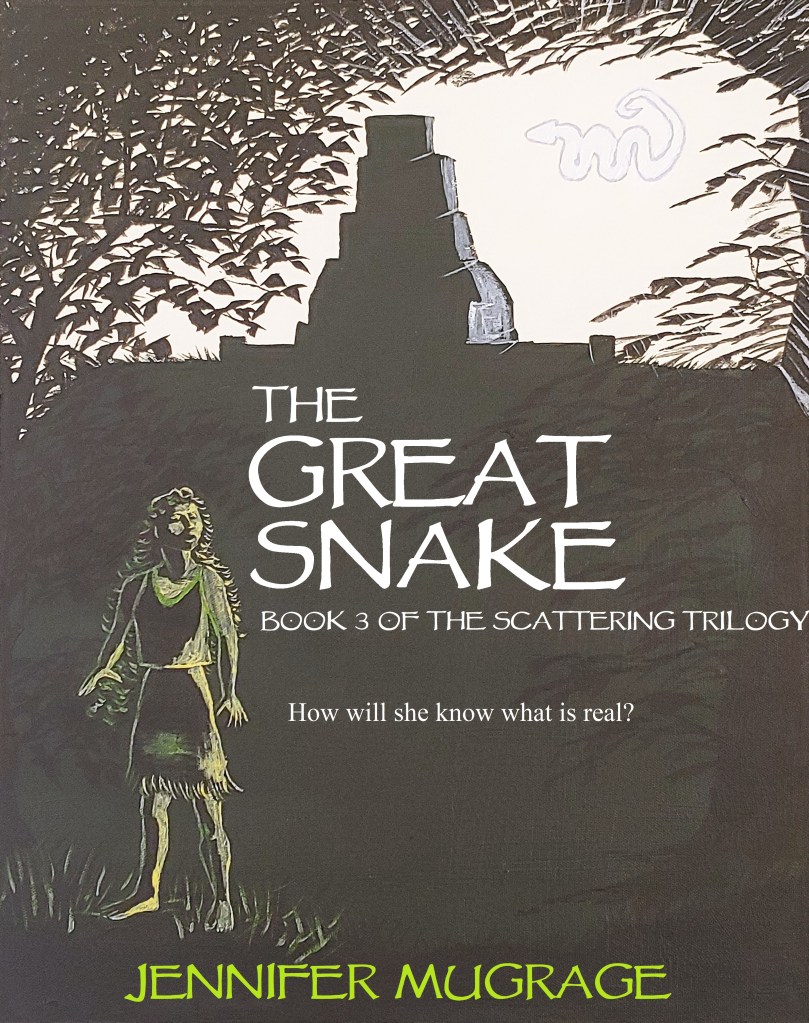

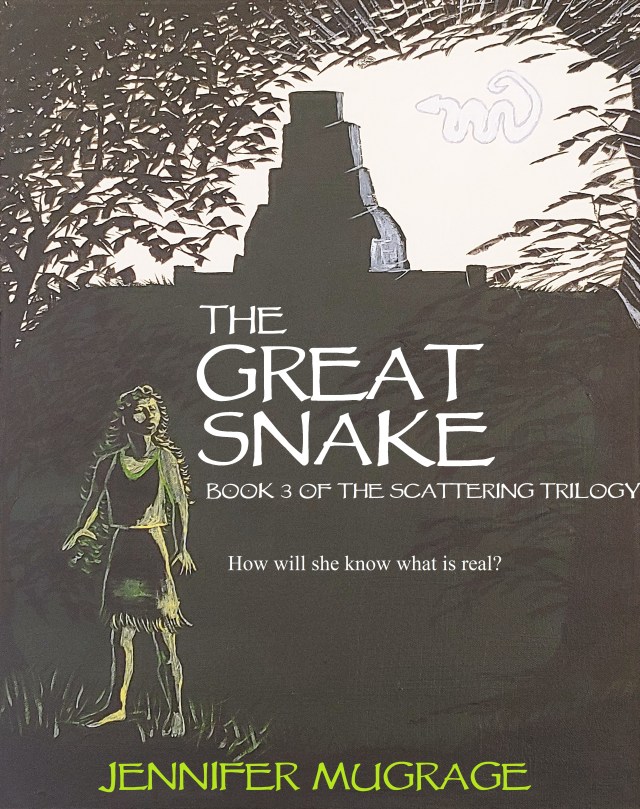

I guess there have been a lot of “snake cities” throughout history. In my third novel, The Great Snake (upcoming, hopefully in 2022), Snake City is founded by a small group who break off from our main group of characters. Their city is like a smaller, less populous version of Poverty Point.

As you can see, our city is much smaller. It overlooks the Mississippi River itself, rather than a bayou. The temple is built not on a man-made mound, but on a natural hill. The people actually live on top of the ridges. They aren’t lapidary craftspeople (at least, not as of the end of the novel). And, finally, this city is about 7,000 years earlier in time than Poverty Point. Other than that, though, it’s exactly the same.

In the cover image, Klee is standing on the lower hill that houses the women’s complex. Behind her, the temple looms over her from atop the hill. It has a Mayan-style roof comb that is facing away from the viewer. In this view, the snake is either hovering in the air just east of the temple, or possibly it is out over the river.