The Senate of the Republic [508 – 49 B.C.] often abused its authority, defended corrupt officials, waged war ruthlessly, exploited conquered provinces greedily, and suppressed the aspirations of the people for a larger share in the prosperity of Rome. But never elsewhere … have so much energy, wisdom, and skill been applied to statesmanship; and never elsewhere has the idea of service to the state so dominated a government or a people. These senators were not supermen; they made serious mistakes … But most of them had been magistrates, administrators, and commanders; some of them, as proconsuls, had ruled provinces as large as kingdoms … it was impossible that a body made up of such men should escape some measure of excellence. The Senate was at its worst in victory, at its best in defeat. It could carry forward policies that spanned generations and centuries; it could begin a war in 264 and end it in 146 B.C.

–Caesar and Christ, by Will Durant, p. 28

Tag: research

Pompeii: A Masterclass in How to Write Historical Fiction

Pompeii by Robert Harris, pub. 2003

Dear Robert Harris,

I am sorry. I am sorry that I left your book, Pompeii, moldering on my bedside bookshelf for … I don’t know … several years after I got it … I don’t know … from my husband’s trucker friend, from the library sale shelf, somewhere like that. I should have picked it up and read it immediately. I thought it was going to be demanding and … you know … educational. I didn’t know it was going to be educational. Or gripping. Or The Perfect Historical Novel.

Spoiler: Vesuvius Blows

I don’t know, reader, whether you would pick up a novel about Pompeii. Perhaps you would worry that the tension would be somewhat lacking, given how everyone knows that the mountain explodes and buries the town. It would be, you might think, sort of like reading a novel called John Dies at the End.

Harris, of course, uses the volcanic eruption’s very fame to his advantage. The people in Pompeii, and Herculaneum, and in the other towns around the bay of Neapolis, don’t know what is about to happen to them. This gives the opportunity for an infinite number of ironic quotes and thematic moments, such as the line, “I ought to die and come back to life more often,” when a narrow escape from death causes a character to be met with newfound respect. You spend much of the book wondering which, if any, of these people are going to survive.

The Historical Background

No, I am not going to sketch all the historical background here. I’ll just tell you that an awful lot is known about Roman society of this period, both general things about the culture, diet, and technology, and specific things about individuals like Pliny the Elder. (And Nero. Nero had a favorite moray eel, did you know that?) Harris makes excellent use of all this research to build a story that grows organically out of the who the characters are and what they value.

At the beginning of the book is a nice clear map of the Bay of Neapolis and surrounding regions, which is critical to visualizing the action of the book. Special attention is given to the Aqua Agusta, an aqueduct which runs from the Apenine Mountains, past all the towns in the region, with spurs providing water to Pompeii, Herculaneum, and so on, until it terminates at the naval base of Misenum, in a reservoir called the Piscina Mirabilis, “Miracle Pool.” When you see how close the Aqua Agusta runs to Vesuvius, you can see that an imminent eruption might well cause problems for the region’s water system.

The Hero

Marcus Attilius, the “aquarius,” comes from a family of men who build and maintain the empire’s aqueducts (which, by the way, like the Aqua Agusta, are often not elevated but rather are underground pipes). He was sent from Rome to Misenum two weeks ago after his predecessor, Exomnius, mysteriously disappeared. When the water running into Misenum first turns sulfurous and then starts to lose pressure, everyone is ready to blame Attilius for not having foreseen or prevented this.

Attilius, realizing the gravity of the situation, orders the city’s water supply to be shut off. There is enough in the Piscina Mirabilis to last Misenum two days with rationing. Attilius, based on which towns have lost water and which haven’t, thinks he knows approximately where the break in the aqueduct is. By pressing very hard, he hopes in two days to sail to Pompeii, send a team inland to find the exact source of the leak, send another team to re-direct the water farther upstream, buy supplies, and work through the night with a team of slaves to fix the blockage. In this way, he hopes to prevent riots and death in the towns without water. The reader knows that Attilius is also racing against time to find the reason the aqueduct broke.

We learn a lot about the Romans’ amazing aqueduct system. All the cities had, essentially, free water as a gift from the Empire. The underground pipe was six feet in diameter, with a three-foot thickness on either side made of the famous Roman cement, made with seawater, which could dry underwater and which got harder with time. There are maintenance manholes at regular intervals, and water sinks along the route which allow the water to drop rocks and silt it’s been carrying. These are then used for gravel.

The great Roman roads went crashing through nature in a straight line, brooking no opposition. But the aqueducts, which had to drop the width of a finger every hundred yards–any more and the flow would rupture the walls; any less and the water would lie stagnant–they were obliged to follow the contours of the ground. Their greatest glories, such as the triple-tiered bridge in southern Gaul, the highest in the world, that carried the aqueduct of Nemausus, were frequently far from human view.

page 181

The Villain

Ampliatus is a former slave. His master, who used him as a toy (yes, the Romans were horrible people), set him free in his will at the age of twenty. Ampliatus, by this time a ruthless social climber, began to amass wealth by buying real estate around Pompeii. Several years before the book opens, the city suffered an earthquake. Most of the aristocrats fled, but Ampliatus is unendingly proud of himself because he stayed, bought up a bunch of buildings on the cheap, fixed them up, and became the nouveau riche. By the time the book opens, he has bought his former master’s estate. His bedroom is the one where he used to be molested. He has gotten his former master’s son in debt to him, and is persuading him to marry Ampliatus’s daughter. He is building an ambitious bathhouse in the middle of the city. As Ampliatus says to the aquarius when he’s trying to corrupt him, water is key to civilization.

As a former slave, Ampliatus outdoes the aristocrats he imitates in both cruelty and ostentatiousness. There is a memorable scene of a feast Ampliatus gives, of the kind that historians would probably call sumptuous. It’s held in Ampliatus’ triclinium (dining room) on a swelteringly hot August night, and no one but Ampliatus wants to be there.

And the food! Did Ampliatus not understand that hot weather called for simple, cold dishes … then had come lobster, sea urchins, and, finally, mice rolled in honey and poppy seeds. … Sow’s udder stuffed with kidneys, with the sow’s vulva served as a side dish … Roast wild boar filled with live thrushes that flapped helplessly across the table as the belly was carved open … Then the delicacies: the tongues of storks and flamingoes (not too bad), but the tongue of a talking parrot had always looked to Popidius like nothing so much as a maggot. Then a stew of nightingales’ livers …

pp. 146 – 147

Reader, I have spared you the most disgusting parts of this dinner.

Ampliatus has commissioned a positive prophecy about the city of Pompeii from a sybil–an older female seer–and is keeping it in readiness for the next time he needs to get the people all excited … probably in order to ensure the election to public office of an aristocrat he has in his pocket. And here is what the sybil has said: Pompeii is going to be famous all over the world. Long after the Caesars’ power has faded, people from all over the world will walk Pompeii’s streets and marvel at its buildings. Ampliatus takes this as a very good sign.

The Scholar

Pliny the Elder, an actual historical person, makes an appearance as a prominent side character. Pliny was stationed as a peacetime admiral at Misenum. When Vesuvius started erupting, it was clearly visible across the bay. Pliny, who had written a whole encyclopedia about the natural world, received a message from an older female aristocrat in Herculaneum, begging him to come and save her library. (In Pompeii, this message is delivered by Attilius.) Pliny launched the navy without imperial permission, intending to save the library and also evacuate the towns near the eruption. But pumice falling from the sky, floating on the water, and clogging the bay prevented the ships from approaching the coast. Pliny and his crew were forced to take refuge belowdecks, and their ship was driven across the bay to Stabiae, where they took refuge overnight. Eventually, they had to evacuate on foot, but Pliny, who was fat and was perhaps suffering from congestive heart failure, chose to stay, and ended up dying in the gaseous cloud that swept along the coast.

The remarkable thing is that during this entire time, Pliny had his scribe with him, and he was dictating his observations about the “manifestation.” His notes were saved. It occurs to me that the stereotype of the British absentminded professor who is never rattled by anything, and always keeps his cool and approaches everything with perfect manners and scientific curiosity (and is an incurable snob), may have roots deeper than England itself.

Go read this book right now!

Despite the large amount of detail in this review, I assure you that I have merely scratched the surface and that this review contains very few spoilers for the novel. I really can’t say anything better about it than that it is, in my estimation, the perfect historical novel. Please go read it if you have any interest at all in the genre.

Quote from the book Alien Intrusion

All you need is a “credible” witness who has had an experience, and then you dare someone else — like the government — to “prove it DIDN’T happen.” Unfortunately, this sort of mindset permeates UFOlogy culture, making it very difficult to get a straight story. … It is not any weight of empirical evidence, rather a proliferation of “let me tell you what I saw” experiences. This does not deny that these experiences may have actually occurred, but we’ve all heard fishing stories… Add to this normal human failing a potentially spectacular UFO claim, with eager media and UFOlogists beating down your door, and often the truth is lost along the way — either in the recounting by the witness or the telling of the tale by the media. This gives you some idea of how difficult the process of determining the truth can be. But, nonetheless, we shall try to determine the true nature of the phenomenon.

Alien Intrusion, by Gary Bates, p. 28

Mind: Blown Book of the Year

Who are the gods?

Over the past several years, my research and reading has led me more and more to the conviction that the entities that people often call the old gods were not “mere mythology.” They were and are real.

Several threads of my thinking have re-enforced each other in coming to this conclusion.

First of all, as a Christian, I reject the Enlightenment-era, materialist notion that there is no spiritual world, that matter is all that really exists. I reject both the strong version of this, in which not even the human mind is real, and the weak version of it, in which we accept that human beings exist as minds, but we try envision as them as “arising” out of matter, and we disbelieve in any other spiritual beings, whether spirits, angels, demons, ghosts, or the one true God. This view, the one I reject, has held sway for most of our lifetimes. Even people such as myself who would not call themselves materialists will lapse into this sort of thinking by default, looking for a physical or mechanical process to explain what is “really” going on behind any claimed spiritual phenomenon.

Another thread in the tapestry has been my interest in the ancient world. Anyone with a passing familiarity with archaeology quickly comes to realize that ancient people were much smarter than they have gotten credit for, at least during the Golden Age of Scientific Triumphalism, the late 1800s and early 1900s. All the good, old-fashioned scientific materialists from this era took it as an axiom that human beings started out as apelike hunter-gatherers, and slowly “ascended,” developing shelter and clothing, “discovering” fire, slowly and painfully inventing various “primitive” tools, and then finally moving on to farming, language, and religion. By hypothesis, ancient people were stupid compared to us now.

Genesis, my favorite history book, tells a very different story. It shows people being fully human from the get-go, immediately launching into writing, herding, weaving, art, music, and founding cities. And in fact, archaeology confirms this. Every year, we discover a more ancient civilization than the evolutionists told us existed. Some recent examples: the Antikythera mechanism is an ancient computer. The Vinca signs are an alphabet that pre-dates Sumeria. Gobekli Tepe is a temple complex that uses equilateral triangles and pi, and dates to “before agriculture was invented” (as is still being claimed). The Amazon basin turns out to have been once covered in cities.

Evolutionists’ dogmatism about early man being stupid has allowed them to ignore all the data that ancient history presents us about the existence of a spirit world. Why should we believe claims (universally attested) about heavenly beings that come to earth to visit, rule over, and even mate with humans? These are primitive people’s attempts to explain purely scientific phenomena that they didn’t understand. But if, as a Christian, I choose to respect ancient people and take seriously their intelligence, then I also have to grapple with their historical and cosmological claims.

Moving on to the third thread. The Bible itself confirms that there were entities called gods (“elohim”), some of whom, at one point in very ancient times, actually came to earth and reproduced with human women, creating a race of preternatural giants, “the heroes of old, men of renown” (Gen. 6:4). The story is told in Genesis ch. 6, but it is assumed and referenced throughout the rest of the Bible and in Hebrew cosmology. This idea is also attested in oral and written traditions worldwide, which universally have gods and giants. A Bible-believing Christian can take seriously the bulk of pagan history, cosmology and myth, whereas a strict materialist evolutionist has to reject it all as primitive superstition.

Two books that have helped me understand Genesis 6 and how it fits into Ancient Near Eastern cosmology were The Unseen Realm by Michael Heiser and Giants: Sons of the Gods by Douglas Van Dorn. I’ve also had conversations with Jason McLean and enjoyed listening to The Haunted Cosmos podcast. The historical record about gods and giants, once forgotten by mainstream Christians in America, is again becoming a topic of interest in the evangelical world.

Part of the Biblical understanding of the gods is that they are created entities who were supposed to help the one true God rule the cosmos. In the course of redemption history, the fallen gods were first banished from appearing physically on earth (in the Flood). At Babel, the gods were each given a nation of men as their “portion” to rule over (Deut. 32:7 – 8), which they did a pretty poor job (Psalm 82). Then God called Abram to make a people for Himself, with the ultimate goal of making all the nations His portion (Ps. 82:8, Ps. 2, Matt. 4:8 – 9). When Christ came, He began to drive the gods out of their long-held territories (Mat. 12:28 – 29). Whenever a region was Christianized, the old gods would first fight back, then become less powerful, and eventually go away altogether. Sometimes, their very names were forgotten. This disappearance of lesser spiritual entities from more and more corners of the earth is the only reason any person could ever seriously have asserted that there is no spirit world.

As a Christian, I am immensely grateful to have grown up in a civilization from which the old gods had been driven. It has been a mostly sane civilization, in which everyday life is not characterized by spooks, curses, possession, temple prostitution or human sacrifice.

This, then, is the background that I brought to Cahn’s book. This mental background helped me to accept many of his premises immediately. If you do not have this background – if you are, for example, a modern evangelical Christian but still a functional materialist – Cahn’s book might be a bit challenging. He dives into the deep end right away. He moves fast and covers a lot of material.

Who is Jonathan Cahn?

In his own words,

Jonathan Cahn caused a worldwide stir with the release of the New York Times best seller The Harbinger and his subsequent New York Times best sellers.

n.b.: I had seen The Harbinger on sale, but I assumed it was fiction in the style of the Left Behind series and avoided it.

He is known as a prophetic voice to our times and for the opening up of the deep mysteries of God. Jonathan leads Hope of the World … and Beth Israel/the Jerusalem Center, his ministry base and worship center in Wayne, New Jersey, just outside New York City.

To get in touch, to receive prophetic updates, to receive free gifts from his ministry (special messages and much more), to find out about his over two thousand messages and mysteries … use the following contacts …

From page 239 of this book

In other words, Jonathan Cahn swims in the dispensational or charismatic stream of Christianity. He calls himself a prophet. That’s a red flag to me, as a Reformed Christian. I believe that the prophetic age ended with John the Baptist (Matt. 11:11 -14). The prophets and apostles were the foundation of the church, and they died out with the first generation of Christians (Eph. 2:19 – 22). This exegesis of Scripture finds confirmation in daily life. I have met Christians who sensed God speaking to them (and have experienced it myself), but I have never met anyone who claimed to be a modern-day prophet, receiving authoritative words from God, who wasn’t a charlatan.

To make matters worse, Cahn asserts that he can “open up the deep mysteries of God” and that we can “find out about his over two thousand messages and mysteries.” This is a direct claim to have exclusive spiritual knowledge that is not available to all in the already-revealed Word of God. If he were just talking about knowledge already found in the Bible, he would call it “exegesis” or “Bible teaching,” not “messages and mysteries.” This claim reveals him to be part of the Gnostic or Hermetic stream of Christianity. Yes, I am using the words “Gnostic” and “Hermetic” loosely. They are big terms with somewhat flexible definitions. However, both are characterized by an emphasis on secret or esoteric knowledge which can only be accessed through a teacher (or, in this case, a prophet) who has been enlightened somehow. To see my posts about Hermeticism and why it is it antithetical to orthodox Christianity, click here, here, here, and here.

What was my approach to this book?

I knew when I picked up this book that Cahn was dispensational, a “prophet,” and therefore fundamentally a false teacher. So, I approached the book not as I would an exegesis by a trusted or mostly trusted, orthodox teacher or scholar like Michael Heiser or Douglas Van Dorn, but rather with curiosity. My interest in the topic of the old gods is such that I can’t ignore what anyone claiming the name of Christ had to say about it. I already knew there was a resurgence of interest in this topic in the Reformed world, and now I wanted to see what the Dispensationalists were saying. I picked it up prepared for anything up to and including rank heresy, but as it turned out, the most heretical thing in the book was the “About Jonathan Cahn” section that I just showed you. The rest was, for someone with my cosmology, mostly pretty hard to disagree with.

The Parable of the Empty House

Cahn spends four very short chapters (Chapters 2 – 5; pages 5 – 22) establishing the ideas I attempted to establish above: that the gods of the ancient world were real spiritual entities who ruled over nations and received their worship. He demonstrates briefly that this was assumed in the Bible and in Hebrew cosmology. He uses the word shedim, a Hebrew word for demon or unclean spirit, which is sometimes used in the Old Testament to describe the gods. He doesn’t get into the idea of elohim, Watchers, or other different names for spiritual entities, or many details of how they fell. Entire books can be (and have been) written about this (see Michael Heiser). However, Cahn wants to move on and see what is going on with these entities in the modern day.

Moving at treetop level, he reviews how the coming of Christ progressively drove the gods out of more and more regions of the earth, in a process that took centuries. He describes civilizations as being “possessed” by the gods they serve. I don’t think he means that every person in a pagan civilization is demon possessed, but as a group, their thinking and behavior is shaped and to some extent controlled by whatever god they serve. As someone who has studied the Aztecs, I can’t disagree. Cahn also points out that it was common, indeed routine, for priests, priestesses, and prophets of the pagan gods to experience actual possession, such as the Oracle of Delphi, the girl with the “python spirit” in Acts 16, or worshippers going into a “divine frenzy.”

Having introduced the concept of possession, Cahn moves on to a parable Jesus told about the dynamics of possession in an individual.

When an evil spirit comes out of a man, it goes through arid places seeking rest and does not find it. Then it says, “I will return to the house I left.” When it arrives, it finds the house unoccupied, swept clean and put in order. Then it goes and takes with it seven other spirits more wicked than itself, and they go in and live there. And the final condition of that man is worse than the first. That is how it will be with this wicked generation. Matt. 12:43 – 45, NIV

Typically of Jesus, this parable works on three levels. The house which is cleansed, left empty, and then re-occupied stands for a person who has been demon-possessed, has been delivered, and then ends up in a worse state than before. And the person, Jesus says, can stand for “this wicked generation.”

Cahn takes this parable and applies it to entire civilizations. He has already established that pagan civilizations were possessed, sometimes literally, by a variety of old gods, to their sorrow. When the Gospel came to them, Christ showed up in person, delivered and cleansed them, and lived in their house. Now, says Cahn, what might happen if a civilization rejects Christ, drives Him out? The house (the post-Christian civilization) has been “swept clean and put in order” by its centuries of Christianity, but it is now “empty,” having driven out Christ. It is now a very attractive vessel for “seven other spirits more wicked than the last.”

I honestly don’t think this is an abuse of Scripture. Cahn seems to be applying the parable in one of the senses in which Jesus meant it. Furthermore, he is not the first to point out that the many wonderful benefits of modern Western civilization are an aftereffect of about 1500 years of Christianity. Some commentators have said that “we are living off interest.” Others have compared us, as a society, to someone sawing off the branch he is sitting on. Doug Wilson has mourned that “we like apple pie, but we want to get rid of all the apple orchards.”

A post-Christian society, say Cahn and many others, for various reasons is vulnerable to much greater evils than a pre-Christian one. In the rest of the book, Cahn will show how the old gods have indeed come back. His focus is on the United States, because he’s an American, but also because the United States has a been a major exporter of culture to the world, and in recent years that culture has been of the demonic variety. Cahn’s book is so persuasive because he is not, as “prophets” often do, sketching a near-future scenario and trying to convince us of it. Instead, he is describing what has already happened.

Which gods, though?

When Cahn first started talking about “the gods” coming back, it occurred to me to wonder, “Which gods?” When Americans or Europeans become openly neo-pagan, I’ve noticed they often go for the gods their ancestors worshipped. So, many people research the Norse gods and cosplay as Vikings … except it’s not just cosplay. Other people are more attracted to the Celtic pantheon. These are the Wiccans. Interestingly, in S.M. Stirling’s Emberverse series, we have a very literal return of the gods when technology vanishes from modern society. Creative anachronists suddenly find that their skills are useful. A Wiccan busker becomes the leader of her own little witch community. Other people get into reviving the Norse religion. It’s a neopagan’s fantasy.

But there are a couple of problems with this. For one thing, neopagans’ version of the ancient religion often looks very different from the actual beliefs of the ancient pagans (many of which have been lost to history). Also, modern neopagans are happy to mix elements of different traditions from opposite sides of the globe: wicca, Tibetan Buddhism, or their kooky version of American Indian religions (probably also not very authentic). I once commented to a neopagan friend of mine (back when we were still friends) that her religion resembled a “personal scrapbook”. And she happily acknowledged this as one of its good points. A DIY paganism, popular with modern individualists, is not the sort of the thing that can become the state religion of a whole society. Finally, actual, hardcore neopagans are not small in number, but they are nowhere near the majority in the United States. Neopaganism does not appear, at this moment, to be the manner in which an entire postChristian society comes under the control of the old gods. And, in fact, that’s not exactly what Cahn has in mind.

America is not made up of any one ethnicity or people group but many, almost all. In many ways America is a composite and summation of Western civilization. So then what gods could relate not to one nation or ethnicity within Western civilization but to all of them or to Western civilization as whole? … The faith of Western civilization come from ancient Israel. The Bible consists of the writings of Israel, the psalms of Israel, the chronicles and histories of Israel, the prophecies of Israel, and the gospel of Israel. The spiritual DNA of Western civilization comes from and, in many ways, is the spiritual DNA of ancient Israel. … The gods, or spirits, that have returned to America and Western civilization are the same gods and spirits that seduced ancient Israel in the days of its apostacy. … If a civilization indwelled by Israel’s faith and word should apostacize from that faith, it would become subject to the same gods and spirits of Israel’s apostacy.

ibid, pp. 34 – 35

The dark trinity

I have a feeling that Cahn, coming from the worldview he does, is setting up this principle as a hard-and-fast rule, and I don’t feel he has really established it as such from Scripture. However, I’m open to it as speculation. Though it’s not, in my opinion, closely argued, his line of reasoning becomes more convincing when we see the gods that he identifies as having returned to America.

He calls them the “dark trinity”:

- Baal (“the lord”): the god of rain in the Ancient Near East, he was often portrayed as riding on a bull and brandishing a thunderbolt. Controlling the rain meant that Baal controlled crops, and hence fertility, wealth, and prosperity. Thus, he was the god of power and wealth, and was a ruler.

- Ishtar/Ashera (Sumerian Inanna): goddess of sex, alehouses, and the occult. Among the Canaanites, Ashera was considered the consort of Baal and “Ashera poles” were the site of orgies.

- Moloch/Molech: The dark god of human sacrifice, particularly child sacrifice. His name means “king.”

Once these gods are identified, we can see that it does not seem so arbitrary that they should be the ones to return. For one thing, they and the God of the Israelites were personal enemies, as it were, battling for control of the same territory, for many centuries. But secondly, these pagan gods come close to being universal.

Baal is your basic male sky god. His name means “lord,” and his essence is basically that of taking power for oneself, rebelling against the Creator. Once we look at him this way, we can see that every pantheon has a Baal. In Ugarit, an ancient Semitic civilization, Baal was understood to be the Creator’s chief administrator over the earth, head of the divine council (credit: Michael Heiser). Baal was actually translated as Zeus in Greek and Jupiter in Rome.

Ishtar, a dangerous female sex goddess, shows up as Inanna in Sumer, one of the most ancient civilizations whose records we can actually read. Cahn spends much of the book delving into Inanna’s characteristics and history, for reasons that will become clear. But, through a process of cultural exchange, she showed up as Ishtar in ancient Babylon (leading to the words Ostara and Easter), Ashera among the Phoenicians (a.k.a. Canaanites), and Aphrodite among the Greeks (Venus among the Romans).

Molech was called Chemosh in Moab. Greek historian Diodorus Siculus translates his name as Kronos (Saturn), the god who devoured his own children. Many many cultures throughout the world have practiced infant sacrifice.

These three gods, then, not only show up by different names in nearly all the cultures of the Ancient Near East right down to Christian times; they not only are the types of entities that show up in nearly every pantheon worldwide, even in the Americas; they also appear to date back to ancient Sumer, which is still a source that is sought by modern neopagans and Hermetic believers. They are not, unfortunately, out of date or obscure. Suddenly, it no longer seems as if they are irrelevant to modern America.

How it went down

Briefly, Cahn argues that cultures (not just America) first let in Baal, who ushers in Ishtar, who ushers in Molech. And he argues that in our culture, this has already happened.

Baal represents the motivation for rebelling against the one true God that seems reasonable. Human beings want prosperity, they want security, they want to do their own thing. They want a god who can reliably make the rain come, the crops grow, the city flourish. They want to have independent, personal power, and not have to humble themselves before or depend upon the Creator. Baal is the god of prosperity, money, and success. Cahn says that America first welcomed Baal. He points to the actual bronze statue of a bull at Wall Street as a literal, though unintentional, idol to Baal, right in the financial center of arguably the most powerful and influential city in our nation.

Once you have Baal, he ushers in his consort, Ishtar. Ishtar is a much more unstable character. As the prostitute goddess, she likes people to engage in sexual chaos. In her instantiation as Inanna, she is emotionally unstable and vengeful, notorious for taking lovers and then killing them (which is why Gilgamesh tried to turn her down). As the patron of the alehouse, she is also the goddess of beer. And she presides over the occult, and with it, drugs. So, Ishtar’s influence began to surge in the 1960s, with sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll, accompanied by a rising interest in the occult and a rising sense of rage. Cahn will have more to say about Ishtar.

Finally, Ishtar ushers in Molech. In the early 70s, after the worship of money and immediately after the Sexual Revolution, American’s highest court legalized the killing of infants. This practice has been defended with religious fervor by its followers ever since. Just as with the Phoenician worshippers of Molech, killing babies has been called not just a necessary evil but a moral good, and opposing this killing has been called a moral evil. Just as when Molech reigned in the Ancient Near East, babies have been killed in their thousands and then in their millions.

We started out just wanting to get ahead, and now here we are, in the darkest place imaginable. But unfortunately, with the gods things can always get worse.

Now, here is where it gets weird

So far, Cahn’s claims have presented themselves to me as insightful, not completely new. Adjusting for his dispensational worldview, what he says makes good sense to anyone who has a passing familiarity with the Old Testament and modern American history. To someone who has had a special interest in the ancient world, they make even more sense. Everything that he has said so far has been hard to argue with, though of course it is still a terrible sight.

Now, however, we are moving into the part of the book that caused me to put Mind: Blown in the title of this post. Cahn spends a good half of the book (pages 115 – 207, out of 240 total) delving into Inanna/Ishtar, and how precisely her characteristics map onto the social changes that have recently been taking place in the United States.

I can’t go into detail about this, but quickly, here are some characteristics of the Sumerian goddess Inanna and her cult. I’ll let you make the applications yourself:

- Inanna had the power to metamorphose and transform: people into animals, men into women and vice versa. (She was obviously not the only old god with this ability.) She liked to blur the boundaries between kinds.

- As a female goddess, she behaved like a fierce male warrior and could also manifest as a young man. Her female followers carried swords. She was known for being bloodthirsty rather than nurturing.

- She could curse human beings by making their men behave like women and their women behave like men.

- But this was sometimes considered a good thing. She had several different kinds of cross-dressing priests, who would curl their hair, tie it up in colorful cloths, dance, and sing in the female dialect.

- In some places, such as in her cult in Turkey, male worshippers would work themselves up into a frenzy and the castrate themselves in her honor. (My note: this may be what the Apostle Paul, who grew up in Tarsus in modern-day Turkey, had in view when he said he wished the Circumcision fanatics would “go the whole way” [Gal. 5:12].)

- Inanna was associated with the rainbow, “stretching herself like a rainbow across the sky.”

- She wanted absolute submission. When spurned or disrespected in any way, she would fly into a rage and seek to destroy the one who had not submitted to her.

- In the ancient world, it was common for gods to be honored with annual festivals. Inanna’s took place in the month of Tammuz, which roughly corresponds to June. It consisted of a large parade, starting at the gate of the city and proceeding to her temple. These parades would feature music, dancing, multicolored cloths and of course her cross-dressing priests and priestesses.

Mind even blown-er

Cahn spends nine chapters (pp. 143 – 172) arguing that the infamous Stonewall riot was, in many ways, the exact night that Ishtar battered down the gates of America. In June 1969 a crowd outside Stonewall, a gay bar in New York City, turned on the police who had raided the place. The police eventually withdrew into the bar, and the crowd, ironically, was now trying to get inside, battering at the doors and even trying to set it on fire. Symbolically, they were trying to get in, just as Inanna famously insisted on being let in to the gates of the underworld. They threw bricks, just as she stood on the brick wall of the city of Uruk to unleash her fury on the whole city because of Gilgamesh.

Cahn argues that New York City is symbolically the gateway of America. As the gay crowd battered at the door of the Stonewall bar, Inanna was simultaneously battering to be let in. As they felt enraged at not being considered mainstream, Inanna too was enraged at, for many centuries, having been driven out.

“If you do not open the gate for me to come in, I shall smash the door and shatter the bolt, I shall smash the doorpost and overturn the doors.”

Myths from Mesopotamia, quoted in ibid, p. 166

Cahn is trying to cover a lot of ground, so he goes over all this at treetop level. I particularly would like to have heard more about the details of the Sumerian sacred calendar, how it relates to the month of Tammuz celebrated by the Israelites, and how its dates in relation to the modern calendar are calculated. Cahn finds significance, for example, in the date June 26, which was the date of the Supreme Court decisions Lawrence vs. Texas (2003), which legalized homosexual behavior; United States vs. Windsor (2013), which overturned the Defense of Marriage Act, and Obergefell vs. Hodges (2015), when the rainbow was projected onto the Empire State Building, Niagara Falls, the castle at Disney World, and the White House, in a clear statement that our nation had declared it allegiance to Inanna. Cahn asserts that June 26 has significance in the commemoration of Inanna’s lover Tammuz, who was ritually mourned every year.

In 1969 the month of Tammuz, the month of Ishtar’s passion, came to its full moon on the weekend that began on June 27 and ended on June 29. It was the weekend of Stonewall. The riots began just before the full moon and continued just after it. The Stonewall riots centered on the full moon and center point of Tammuz.

ibid., p. 170

The day that sealed Stonewall and all that would come from it was June 26, 1969. It was then that deputy police inspector Seymour Pine obtained search warrant number 578. … On the ancient Mesopotamian and biblical calendar, [the warrant] took place on the tenth day of the month of Tammuz. Is there any significance to that day? There is. An ancient Babylonian text reveals it. The tenth of Tammuz is the day given to perform the spell to cause “a man to love a man.”

ibid, p. 171

This does seem really striking at first blush. Note, though, that in the typical manner of esoteric gurus, if the date June 26 doesn’t fall on exactly the beginning of the Stonewall riots, Cahn takes something significant – or that he asserts is significant – that happened on a date near by the riots, and points to that. Why are we considering the obtaining of the warrant to be the event that “sealed” the riots? Because otherwise, the dates don’t work out quite right.

The timing of the Supreme Court decision had nothing to do with the timing of Stonewall … it was determined by the schedule and functioning of the Supreme Court. And yet every event would converge within days of the others and all at the same time of year ordained for such things in the ancient calendar… So the ruling that legalized homosexuality across the nation happened to fall on the anniversary of the day Stonewall was sealed. The mystery had ordained it.

ibid., p. 203

I must say, if Graham Hancock were covering this subject, he would devote several lengthy chapters to the calendar aspect of it. Whole books have probably been written about this. It did make me want to study in more depth ancient Sumeria, with the same terrible fascination with which I have scratched the surface of studying the Aztecs and the Mayas. I’m not super good at the mathematical thinking required to correlate calendars or unpack ancient astronomy, though I do enjoy reading other people’s work.

Not being a dispensationalist, I am less concerned with exact numbers and dates being the fulfillment of very precise prophecies, and more concerned with the general, overall picture of nations turning toward or away from God. I don’t think we need the repeated date of June 26 to match up with the Sumerian calendar perfectly in order to see that America has rejected heterosexuality, and indeed the whole concept of the normal, in a fit of murderous rebellion against the Creator, and that this is entirely consistent with the spirit of this particular goddess.

Nevertheless, I have only named a few striking parallels between the Stonewall riots and the myths and cult of Inanna. Cahn weaves it into a compelling story, and hence the title of this blog post.

Now, about times and seasons I do not need to write you

I’m also a little concerned with the amount of power that Cahn seems to be granting here to Inanna, and to the whole Sumerian/Babylonian sacred calendar. I have no doubt that this ancient entity would prefer to bring back her worship in the month it used to be conducted, around the summer solstice every year. I realize that every day in the Babylonian calendar was considered auspicious or inauspicious for different activities, due to the labyrinthine astrological bureaucracy that the gods had set up. No doubt, the gods would prefer to bring back as much of that headache-inducing system as possible. However, this does not mean that they are always going to get their way. It is not “ordained” in the same sense that the One God ordains things by His decretive will. He is in charge of days, times, and seasons, and of stars and solstices. He is the one who made these beings, before they went so drastically wrong.

Then Daniel praised the God of heaven and said,

“Praise be to the name of God for ever and ever; wisdom and power are His.

He changes times and seasons; he sets up kings and deposes them.

He gives wisdom to the wise and knowledge to the discerning.

He reveals deep and hidden things; He knows what lies in darkness, and light dwells with Him.”

Daniel 2:19 – 22

To his credit, Cahn, after scaring the pants off anyone who is not on board with bringing back full-on Sumerian paganism, gives a nice, clear Gospel presentation at the end of his book. His last chapter, The Other God, points his readers to Yeshua:

Even two thousand years after His coming, even in the modern world, there was still none like Him among the gods. There was none so feared and hated by them. … He was, in the modern world, as much as He had been in the ancient, the only antidote to the gods — the only answer. As it was in the ancient world, so too in the modern — in Him alone was the power to break their chains, pull down their strongholds, nullify their spells and curses, set their captives free.

ibid, p. 232

Hermeticism: The Awful Truth

Sorry, folks. Life has continued to be busy. So this weekend, I’m re-posting another one of my most-often-viewed essays for your edification.

Discovering the Extent of the Problem

I learned the word Hermeticism recently.

Here’s an extended simile of what my experience was like in doing a deep dive on this word.

Imagine that your drain keeps backing up. You take a look, and discover a root. You have to find at what point the roots are coming into the pipe, so you do the roto-rooter thing. It turns out that the roots are running through the pipe all the way down to the street and across the street and into the vacant lot, where there is a huge tree.

And oh, look, it’s already pulled down the neighbor’s house!

That’s what it was like. (Oh, no! It’s in my George MacDonald pipe too!)

What Methought I Knew

I’ve listened to a number of James Lindsay podcasts, and he talks a lot about Hegel. In discussing what exactly went wrong with the train wreck that is modern education and politics, James has to dive deep into quite a few unpleasant philosophers, among them Herbert Marcuse, Jaques Derrida, Paolo Friere, and the postmodernists. And Hegel.

I had heard James describe before how Hegel saw the world. Hegel had this idea that progress is reached by opposite things colliding and out of them comes a new synthesis, and then that synthesis has to collide with its opposite and so on until perfection is reached. This process is called the dialectic. Marx took these ideas and applied them to society, where there has to be conflict and revolution, but then the new society that emerges isn’t perfect yet and so there has to be another revolution and so on until everything is perfect and/or everyone is dead.

Obviously I am simplifying a lot. James can talk about this stuff for an hour and he is simplifying too, not because these ideas are themselves complicated but because Hegel produced a huge dump of words, and he came up with terminology that tried to combine his ideas with Christian concepts so that they would be accepted in his era. Anyway, the word dialectic is still used by postmodern writers like Kimberle Crenshaw, and it is a clue that they think constant revolution is the way to bring about utopia.

So, I was familiar with Hegel through the podcasts of Lindsay, and I was also familiar enough with Gnostic thought to at least recognize it when it goes by, as it so often does. For one thing, you kind of have to learn a little bit about Gnosticism if you are a serious Christian, because gnostic (or at least pre-gnostic: Platonic, mystery religion) ideas were very much in the air in New Testament times, and many of the letters of the New Testament were written to refute these ideas. Also, Gnosticism, particularly the mind/body duality, has had such an influence on our culture that it’s hard to miss. It’s present in New Age and neopagan thought, and it’s called out in Nancy Pearcey’s book Love Thy Body for the bad effects it has had on the way we conceive of personhood.

So that’s the background.

Several months ago, I was listening to Lindsay give a talk summarizing his recent research to a church group. He was talking about theologies: systems of thought that make metaphysical and cosmological claims, and come with moral imperatives. And he dashed off this summary, something like the following:

“You could have a theology where at first all that exists is God, but He doesn’t know Himself as God, so in order to know Himself he creates all these other beings, and they are all like pieces of God but they don’t know it, and their task is to become enlightened and realize that they, too, are God, and when they realize this, eventually they will all come back together, but now God is self-conscious because of the process of breaking He’s been through.”

And I’m thinking, Sounds like Pantheism, or maybe Gnosticism.

And James says, “That’s the Hermetic theology.”

And I’ve got a new word to research.

Kind of a Weird Name

So, why is it called Hermeticism? Does it have to do with hermits?

My first foray into Internet Hermeticism immediately showed that the school of thought was named for a guy named Hermes, as in this paragraph from wiki:

Hermeticism, or Hermetism, is a label used to designate a philosophical system that is primarily based on the purported teachings of Hermes Trismegistus (a legendary Hellenistic combination of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth).[1] These teachings are contained in the various writings attributed to Hermes (the Hermetica), which were produced over a period spanning many centuries (c. 300 BCE – 1200 CE), and may be very different in content and scope.[2]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hermeticism

One of my search hits, I can’t remember which one, said that Hermeticism is “often confused with Gnosticism.” O.K., so if it’s not Gnosticism, that means I know less than I thought and it’s all the more reason to research.

I also found avowedly Hermetic web sites like Hermetic World, whose “summary” is actually more of an attempt to draw you into their movement:

Hermeticism – The secret knowledge

Hermeticism is an ancient secret doctrine that dates back to early Egypt and its innermost knowledge has always been passed on only orally. In each generation there have been some faithful souls in different countries of the world who received the light, carefully cultivated it and did not allow it to be extinguished. Thanks to these strong hearts, these fearless spirits, truth has not been lost. It was always passed on from master to disciple, from adept to neophyte from mouth to ear. The terms “hermetically sealed”, “hermetically locked”, and so on, derive from this tradition and indicate that the general public does not have access to these teachings.

Hermeticism is a key that gives people the possibility to achieve everything they desire deep in their hearts, to develop a profound understanding of life, to become capable of decision making and responsibility; and to answer the question of meaning. Hermeticism offers a hidden key to unfolding.

Nobody can teach this knowledge to himself. Even in competent books like Kybalion, the teaching is only passed on in a veiled way. It always requires a master to pass on the wisdom to the able student. Today, as in the past, authentic mystery schools are a way to acquire this knowledge. The Hermetic Academy is one of these authentic schools.

https://www.hermetic-academy.com/hermeticism/

This is certainly the genuine article, but it is perhaps not the first place to go. I wanted to learn about the basic doctrines from a neutral source, simply and clearly described. I didn’t want to have to wade through a bunch of hand-waving to get there, at least not at first. Still, I suppose we shouldn’t be surprised that Hermetic World tries to cast a mysterious, esoteric, yet somewhat self-help-y atmosphere on their first page. After all, it is a mystery religion.

Well, at least now I know why it’s called Hermeticism. It’s basically an accident of history, due to the name of the guy to whom the founding writings were attributed.

Time to move on to a book.

Moving On to a Book

I am fortunate to be descended from a scholar who has a large personal library, heavy on the theology.

I asked my dad.

Serendipitiously, he had just finished reading Michael J. McClymond’s two-volume history of Christian universalism (the doctrine that everyone is going to heaven), and he remembered that Hermeticism entered into the discussion. He was happy to lend it to me. You can see all the places I’ve marked with tabs. Those are just the ones where Hermeticism is directly mentioned. I hope you now understand my dilemma.

In McClymond’s Appendix A: Gnosis and Western Esotericism: Definitions and Lineages, I found at last the succinct, neutral summary I was looking for:

[“Hermetism”] as used by academics refers to persons, texts, ideas, and practices that are directly linked to the Corpus Hermeticum, a relatively small body of texts that appeared most likely in Egypt during the second or third centuries CE. … “Hermeticism” is often used in a wider way to refer to the general style of thinking that one finds in the Corpus Hermeticum and other works of ancient gnosis, alchemy, Kabbalah, and so forth. “Hermeticism” sometimes functions as a synonym for “esotericism.” The adjective “Hermetic” is ambiguous, since it can refer either to “Hermetism” or “Hermeticism.”

McClymond, p. 1072

O.K.

So it isn’t that different from Gnosticism after all.

“Esoteric,” by the way, means an emphasis on hidden or mystical knowledge that is not available to everyone and/or cannot be reduced to words and propositions. “Exoteric” refers to the style of theology that puts emphasis on knowledge that is public in the sense that it is written down somewhere, asserts something concrete, can be debated, etc.

Even though I have literally just found an actual definition of the word that is clear enough to put into a blog post, in the time it took me to find this definition I feel that I have already gotten a pretty good sense of what this philosophy is like. Perhaps it helps that it has pervaded many, many aspects of our culture, so I have encountered it many times before, as no doubt have you.

I began to peruse the tabs in the volumes above and read the sections there, in all their awful glory.

Yep, James Lindsay in fact did a pretty good job of explaining the core metaphysic of Hermeticism. Of course, this philosophy brings a lot of things with it that he didn’t get into. If we and all beings in the universe are all made of the same spiritual stuff as God Himself, it follows that alchemy should work (getting spiritual results with physical processes and the other way round). It follows that astrology should work (everything is connected, and the stars and men and the gods not only all influence each other, but when you get down to it are actually the same thing). It follows that reincarnation should be a thing (the body is just a shell or an illusion that is occupied by the spirit, the spark of God). It follows that there are many paths to God, since we are all manifestations of God and will all eventually return to Him/It. It follows that the body is not that important (in some versions of this philosophy, matter is actually evil). Therefore we should be able to physically heal ourselves with our minds. Our personhood should be unconnected to (some might say unfettered by) our body, such that we can be born in the wrong body, or we can change our sex or our species if we want to. There might also be bodies that don’t have souls yet (such as unborn babies), and so it would be no wrong to destroy them. Also, since matter is not really a real thing, it follows that Jesus was not really incarnated in a real human body and that He only appeared to do things like sleep, eat, suffer, and die. Also, since we are all parts of God like He is, He is not really one with God in any sense that is unique, but just more of an example of a really enlightened person who realized just how one with God He was.

I imagine that about twenty pop culture bells have gone off in your mind as you read that preceding paragraph. You might also have been reminded of the Church of Jesus Christ of the Latter-Day Saints, which teaches that we were all pre-existent souls literally fathered by God out of some sort of spiritual matter before we came to earth to be born.

So, What the Heck Is It?

Hermeticism is not just one thing. It’s a whole human tradition of thought. It had a lot of streams flowing into it, like Plato, first-century mystery religions, Gnosticism, and early attempts to reconcile Christianity with these things. It has a lot of streams flowing out of it, like many Christian mystics of varying degrees of Christian-ness; Origen; Bohme; Hegel; medieval and Renaissance alchemy; the Romantic literary movement; Mormonism; New Age thinking; identity politics; transhumanism; Shirley McLaine; The Secret, and the movie Phenomenon.

Not all of these thinkers hold to the exact same set of doctrines. In a big philosophical movement like this, almost every serious thinker is going to have his or her own specific formulation that differs from everyone else’s in ways that seem really important to people on the inside of the system. So anyone who is an insider or who has made it their life’s work to research any of the things I mention above (and many others besides) could come along and point out errors or overgeneralizations in this article and make me look like I don’t know anything. That’s partly because it’s a huge historical phenomenon and I actually don’t know much of all there is to know. It’s also partly because these mystery religions delight in making things complicated. They love to add rituals and symbols and secret names and to discover new additional deities that are personifications of abstract ideas like Wisdom. It’s supposed to be esoteric. That’s part of the fun.

Another reason it’s difficult to describe Hermeticism accurately is that when all is one, it is really difficult to talk about anything. In this view of the world, when you get right down to it there is no distinction between spirit and matter, creator and creature, man and woman, conscious and inanimate, and the list goes on. I called it Hermeticism at the beginning of this paragraph, but I was tempted to write Hermeticism/Gnosticism, or perhaps Hermeticism/Gnosticism/alchemy/mystery religions/the New Age/Pantheism/postmodernism. If you’ve ever read any New Age writers, you’ll notice that they tend to write important terms with slashes like that (“Sophia/the divine feminine”). That’s because it’s all one. They don’t want you to forget that. They don’t want to forget it. Even if these ideas do not go very well with the human mind, and they tend to break it if you keep trying to think them.

In a sense, Hermeticism and all these other related movements are very diverse and not the same at all. In another sense, it’s all … the same … crap.

Ancient Maps of Antarctica Debunked. Maybe. Also, We Are All Idiots

Playin’ the Hits

This is a repost. These past weeks have been busy, what with wrapping up the school year, many family events, and illness. (I have a fever right now, and it’s making my online comments amazing.) So I give you this, one of my most-often-viewed posts of all time.

Disclaimer

Like most sane people, I hate Internet debates. Love/hate, that is. Even in real life, I’ve always found it hard to let a debate go. I’ve sometimes stubbornly backed positions that later turned out to be false, and on the other end of the spectrum I’ve gotten scared by ad hominems and conceded stuff I didn’t need to concede. Almost no matter how the debate goes, I end up feeling like an idiot.

I don’t want this site to become a debating site. But a few weeks ago, I posted a wild historical theory and invited you guys to critique it. Benjamin did, in the comments, here. So, for the integrity of this site, I’ve got to respond to the critique found in the link. If you don’t like Internet debates, please please skip this post.

The link that Benjamin posted to is to a site called Bad Archaeology. The site has two guys’ names on it, but at appears to be mostly written by one guy. (At least, he is the one who responds to comments.) Let’s call him KFM. I am not posting his full name here nor am I linking to his web site, because I don’t want to attract his attention because I hate Internet debates! However, you can easily find his site by Googling it.

The site exists to debunk “Bad Archaeology” (caps in the original), which mostly means various wild theories like the ones we’ve been discussing about lost civilizations, aliens, etc. It calls proponents of these theories Bad Archaeologists and it fights them with facts, with mischaracterization of their positions, and sometimes with mockery. And by capitalizing its references to them. Always fun.

Summary of the Refutation

KFM’s main arguments against Hancock’s idea that the Piri Reis, Orontius Finaeus, and Buache maps come from an older source are as follows:

-Piri Reis SAID he got his data for the New World part of his map from Columbus. This is confirmed because he faithfully reproduces some of Columbus’s errors, such as showing Cuba as part of the mainland.

-Most Bad Archaeologists consistently spell Orontius Finaeus’s name wrong. (Oronteus.) This shows they don’t know what they’re talking about.

-There are major errors in Reis’s and Finaeus’s depictions of Antarctica. So we cannot claim that a supposed older source map was accurate. (More on this in a second.)

-Only one version of Buache’s famous map exists that shows Antarctica. It is in the Library of Congress. Other versions of the same map just show a big blank space there.

-Buache was an accomplished geographer who had a theory that there must be a landmass at the bottom of the world. He also theorized that within it, there must be a large inland sea that was the source of icebergs. So, if the map he supposedly drew is not a hoax and was in fact drawn by him, then he just made it up out of pure speculation. In fact, he wrote “supposed” and “conjectured” all over it.

-He also shows ice and icebergs all over it. This renders ridiculous the idea that it is a map of Antarctica before the continent was covered in ice.

-Buache’s and Finaeus’s maps don’t match Reis’s or each other, so clearly they cannot have come from a single source map, let alone an accurate one.

The Strong

KFM’s arguments look, at first glance, super convincing. Some of them are dead on.

The strongest part of KFM’s argument is this:

“[Charles] Hapgood, [Hancock’s source for this theory], assumed that the original source maps, which he believed derived from an ancient survey of Antarctica at a time when it was free from ice, were extremely accurate. Because of this, he also assumed that any difference between the Piri Re‘is map and modern maps were the result of copying errors made by Piri. Starting from this position, it mattered little to Hapgood if he adjusted the scales between stretches of coastline, redrew ‘missing’ sections of coastline and altered the orientation of landmasses to ‘correct errors’ on Piri’s map to match the hypothesised source maps …. Hapgood found it necessary to redraw the map using four separate grids, two of which are parallel, but offset by a few degrees and drawn on different scales; a third has to be turned clockwise nearly 79 degrees from these two, while the fourth is turned counterclockwise almost 40 degrees and drawn on about half the scale of the main grid. Using this method, Hapgood identified five separate equators.”

This is pretty damning to the theory. It’s not necessarily fatal to the idea that Reis used an obscure ancient source among the 20 that went into his map. After all, copying errors do happen, especially when we are trying to compile a bunch of maps from different eras of places we have never surveyed ourselves. But that’s an unfalsifiable claim, so let’s leave it. Regardless, Hapgood’s shenanigans certainly are fatal to the idea that this ancient map, if it existed, was astonishingly accurate in latitude and longitude.

The Not So Strong

But alongside this excellent argument, KFM also includes a bunch of inconsistent ones:

“All in all, the Piri Re‘is map of 1513 is easily explained. It shows no unknown lands, least of all Antarctica, and contained errors (such as Columbus’s belief that Cuba was an Asian peninsula) that ought not to have been present if it derived from extremely accurate ancient originals. It also conforms to the prevalent geographical theories of the early sixteenth century, including ideas about the necessity of balancing landmasses in the north with others in the south to prevent the earth from tipping over.”

So, the map does not show Antarctica, but one sentence later it does show Antarctica, but Antarctica was only put there because contemporary geographical theory demanded it. Also, note the assumption that the ‘extremely accurate originals’ are supposed to have included all of the Americas as well as Antarctica. That’s not my understanding of Hancock’s claim.

It’s also not clear whether KFM is claiming that all the data for Reis’s map came from Columbus. If he is, this inconsistent with both Hancock’s claim (and KFM’s own showing) that Reis said the map was compiled from 20 others, including among them a map whose source was Columbus.

Similarly, KFM shows errors on Orontius Finaeus’s map, although he admits that “There are fairly obvious similarities between the general depiction of the southern continent by Orontius Finaeus and modern maps of Antarctica.”

The Buache Map Shows an Archipelago

For the Buache map, KFM contends that Buache essentially made up the entire map to satisfy a geographical theory he had, namely that there must be a land mass at the bottom of the world to balance the land at the top (this was a popular theory at the time), and that it probably had a large inland lake in it with two major outlets leading to the sea (this was Buache’s own brilliant guess, and he thought this lake must be the source of the icebergs that navigators encountered in the southern sea).

I take KFM’s word that Buache had this theory, and that his map shows ice and icebergs on Antarctica, which KFM says “makes the claims that Buache’s map shows an ice-free Antarctica all the more bizarre.”

Well, sort of. But actually, Hancock’s claim is that the source map Buache used shows Antarctica early in the process of icing over. Also, given Buache’s theory, it would not be surprising if he had added ice and icebergs to any other data that he may have had.

“Over several parts of the southern continent, Buache writes conjecturée (conjectured) and soupçonnée (suspected).” KFM thinks this is conclusive proof that Buache basically invented the interior of Antarctica on his map, based purely on his own theory. That could be. But I have to say, if it is, he did a great job! He does not just draw a round mass, attach the few islands and promontories that he knows about (New Zealand, which he took for a peninsula, and the Cape of the Circumcision), and then draw a lake in the middle. Instead, he has a waterway offset between two unequal land masses. It corresponds surprisingly well to the shapes of the ranges of mountains and low areas that we now know Antarctica has.

The “Well, I’ll Bet You Didn’t Know About … This!” Argument

Besides these arguments, KFM includes a lot of interesting history about the biographies of these cartographers. Almost half his page about Finaeus is taken up with the cartographer’s biography, even though it has little to do with claims about his map (beyond boosting his credentials, which I would think Hancock would also want to do). Similarly, with Buache we are given: “The claims of Bad Archaeologists about Buache’s map ignore a crucial fact: he was the foremost theoretical geographer of his generation, whose published works include hypotheses about the Antarctic continent.” I’m not sure why Buache’s eminence is supposed to be a devastating blow to any claims about his map, but again we are treated to a long and interesting biography before KFM finally gets to Buache’s theories about a southern continent.

This style of argument reminds me of people who think they have shown the Bible is not divinely inspired merely because they can show that it happened in a particular historical context and is expressed in a particular historical idiom. They will trot out some tidbit of historical context that they assume is complete news to some Bible scholar who has been studying ANE history his whole life. Their line of argument is based on a misunderstanding of what divine inspiration is claimed to be. They assume that if something is claimed to be the Word of God, it must have come to humanity in an abstract, context-free, propositional and not literary or historical form. (They also assume that it must cover all knowledge in the world, e.g. so that the discovery of North America was supposed to somehow shake our faith in the Bible.)

KFM’s argument about these maps is exactly the same kind of argument. He gives a bunch of historical context about these cartographers and thinks that refutes Hancock’s claims. It’s as if Hancock had been arguing that Piri Reis, Finaeus, and Buache were born of virgins, went through life without interacting with anyone, and then one day, without any context whatsoever, this complete, easy-to-interpret map from an ancient civilization dropped out of the sky into their hands. Well, that certainly isn’t the argument that Hancock makes in his book. His argument is (or was; he has apparently retracted it) that there were several source maps, made over centuries or millienia, which traced the progressive growth of the Antarctic ice cap. He does not claim that these were complete, accurate world maps or even that they showed the Americas. “Someone who knew what they were doing once mapped Antarctica.” That’s the basic claim.

When We Think We Don’t Have Preconceptions

It turns out that there is a more than coincidental similarity between the way KFM caricatures Hancock’s claims and the way that some people caricature claims about the Bible. KFM, in fact, classes Biblical Archaeology as a subset of Bad Archaeology. The following quotes should give you a sense of his general attitude:

“Some Bad Archaeology is just so outrageously Bad that it can only be examined charitably by assuming that its proponents are slightly confused. How else can you explain the complete lack of critical judgment, the belief in ancient fairy stories, the utter absence of logical thought they display? Either that, or they have a particular agenda, usually driven by a religious viewpoint.

Biblical Archaeology, which has been described as excavation with a trowel in one hand and a Bible in the other, is a specialised branch of archaeology that often seems to ignore the rules and standards required of real archaeology. Conducted for the most part, by people with an explicitly religious agenda (usually Christian or Jewish), it is a battleground between fundamentalist zeal and evidence-based scholarship … If we can’t find evidence for Solomon’s glorious empire, it must be that we’re not interpreting the archaeological data correctly and that a big discovery is just around the corner (the ‘Jehoash inscription’ leaps to mind in this context). If contemporary Roman documents don’t mention Jesus of Nazareth, why here’s an ossuary that belongs to James, his brother… It’s all very much centred around contentious objects, poorly-dated sites and great interpretative leaps that the non-religious may find astounding.”

Got that? If you believe in a historical Solomon or even a historical Jesus, you’ve just been dubbed a Bad Archaeologist. Welcome to the club, friends.

I mention this attitude not because it’s off-putting, but because it tells us something about KFM’s mindset and about what it would take to convince him that something is “good” archaeology. I’m guessing that any evidence of advanced civilizations older than about 4,000 BC is going to be dismissed out of hand. As will any evidence showing that humanity might have declined, rather than slowly progressed, over our history.

Conclusion: Inconclusive

Going back to the maps, what has been shown here? I would say it’s inconclusive. The maps are less accurate than Hancock claims and far less accurate than I made them sound in my original post, because I was going over Hancock’s theory at treetop level and didn’t bother to get off into the weeds when he discusses the details of the maps. (As I still haven’t done in this post. I would like to, but my time is limited.)

On the other hand, I think the Finaeus and Buache maps especially are more accurate than we would expect of maps that had been drawn out of pure conjecture, without any source at all. It looks like more was known about Antarctica in the 16th century than we previously assumed, whatever the source of that knowledge.

So it’s not a case of “Lost civilization proven!” but neither is it “Nothing to see here.” The most we can say is that something strange is going on, but we don’t know what. To paraphrase Andrew Klavan, KFM isn’t wrong to think Hancock and Hapgood are wrong; but he is wrong to think that he himself is right.

About the theory of earth crust slippage, I feel the same way. On the one hand, it’s a pretty hard theory to swallow on geological grounds. (For example: if a big section of the earth’s crust pivoted around the North American plains – even granted that this could happen – shouldn’t there be some kind of seam where the edge was?) On the other hand, clearly something weird happened, or we wouldn’t have Siberia being ice-free when Canada was ice-covered. Nor would we have flash-frozen tropical plants and baby mammoths.

So, in conclusion, nobody knows anything, boys and girls. Let us eat, drink and be merry.

Hundreds of Thousands of Ancient Stone Structures in Saudi Arabia

On Oct. 17, Live Science published an article describing a highly unusual type of site – called gates in the Harret Khaybar area, that my colleagues and I had systematically catalogued and mapped and were to publish in the scientific literature in November. That sparked immediate and extensive international media coverage, including features in The New York Times, Newsweek and the National Geographic Education Blog. Four days after the article was published on Live Science, I got an invitation from publication from the Royal Commission for Al-Ula, in northwest Saudi Arabia, to visit that town. The Al-Ula oasis is famous for hosting the remains of a succession of early cultures and more recent civilizations, all strewn thickly among its 2 million-plus date palms. As a Roman archaeologist, I had known this oasis for over 40 years as the location of Madain Salih, Al-Hijr — ancient Hegra, a world-class Nabataean site adopted by UNESCO.

Four days after the invitation from the Royal Commission, my colleague Don Boyer, a geologist who now works in archaeology, and I were on our way to Riyadh. Almost immediately, on Oct. 27 to Oct. 29, we began three days of flying in the helicopter of the Royal Commission. In total, we flew for 15 hours and took almost 6,000 photographs of about 200 sites of all kinds — but mainly the stone structures in the two harrat.

Though we didn’t have much notice, Boyer and I spent three days before our visit looking over the sites we had “pinned” and catalogued using Google Earth over several years. We then, relatively easily, planned where we wanted to fly in order to capture several thousand structures in these two lava fields. Our helicopter survey was probably the first systematic aerial reconnaissance for archaeology ever carried out in Saudi Arabia. It was possible only because of the publication of the Live Science feature article describing my research on the gate structures, and the resulting international media coverage, which caught the attention of the Royal Commission.

-Prof. David Kennedy, in this LiveScience article, November 2017

I am just so excited about this, people. Just so excited.

I had heard that there were large stone structures, called “gates,” in Saudi Arabia. I’d even blogged about it before. But I had no idea that there were hundreds of thousands. Hundreds of thousands. Saudi Arabia must be simply covered in these things.

It gets better. Guesses are that they date back 7,000 years (pre-Flood? Immediately post-Flood?). We know because many of them have been covered by lava flows in the interim. The Bedouins say they are “the works of the old men.”

It gets better. Why was the extent of these structures previously unknown? Must be racism, right? Evil European archaeologists didn’t expect the ancient inhabitants of Saudi Arabia to have built stuff like this?

Why, no. These structures are waaay out in the desert, known only to the locals. Almost impossible to find on foot. They are best surveyed from the air. Well, shortly after the last two World Wars (when small planes first came into general use), the Arab states started to achieve their independence from Britain and France. And they became closed states. They didn’t want anybody flying over their land. So, these amazing structures have been unknown and underappreciated, because those archaeologists who were interested, weren’t allowed to observe them.

So, let’s review. This story simply has everything guaranteed to make Out of Babel squirm with joy. Old, mysterious structures, really old, pre-dating even the amazing Nabatean civilization (the folks who built Petra), HUNDREDS OF THOUSANDS of them, purpose unknown, not generally known to exist because of remote location and closed country. Not only would this make a great movie, but it is the kind of thing that is continually popping up all over the world. Apparently, there is literally tons of evidence of smart humans building advanced civilizations, in just about every country on earth, yet we moderns have been unaware of this for a variety of reasons. Some of these reasons weren’t our fault (how were we supposed to know?), some were (we were blinded by the evolutionary narrative that says prehistoric people weren’t “advanced”).

When I say “advanced civilizations,” I mean a variety of different things by that. I mean cities with sophisticated water systems like Teohihuacan, observatory/computers like Stonehenge, observatory/cities like Poverty Point, temples using advanced geometry like Gobekli Tepe, pyramids like the ones in Bosnia, giant geoglyphs like the Nazca Lines and Serpent Mound and, apparently, these Saudi Arabian gate things. I also mean stones that appear to have been drilled, or precisely molded like the ones at Puma Punku.

If you have time, please follow the link and look up the LiveScience article. It’s worth reading the whole thing, and includes a video with views of the structures from an airplane.

Stone Age Alphabets

Originally Posted as, “Writer: The World’s Third Oldest Profession”

Writing is a human practice.

Of course it is possible to have a human society without writing, but the impulse to devise a writing system, looked at historically, may have been the rule rather than the exception.

This is counter-intuitive, of course. “Symbolic logic” seems like it ought to be unnatural to humans, especially if we are thinking of humans as basically advanced animals, rather than as embodied spirits. But if we think of mind as primary, everything changes. It’s telling that reading and writing are one of the learning channels that can come naturally to people, in addition to the visual, the audio, and the kinesthetic. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

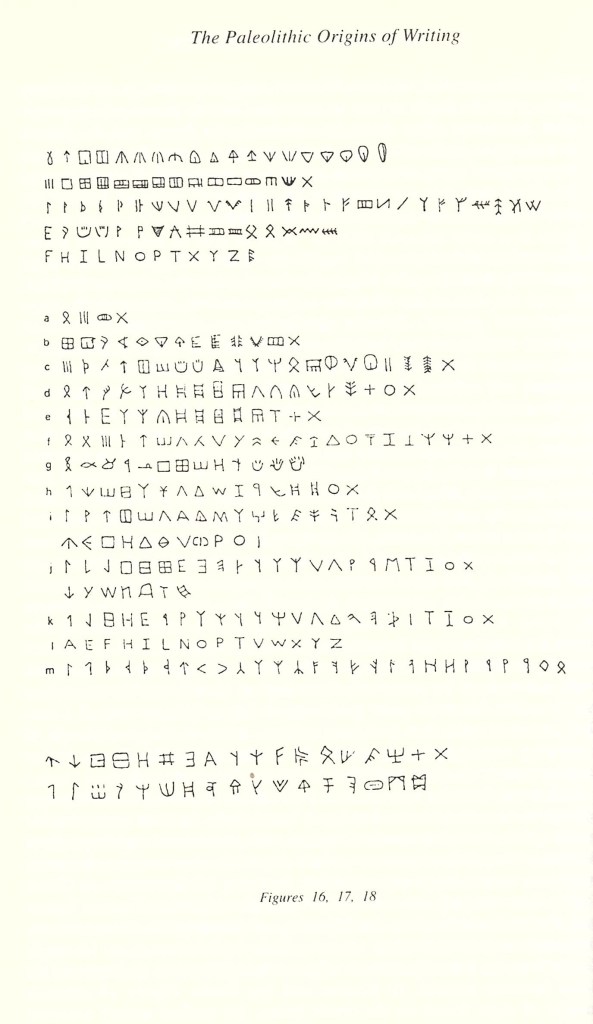

Welcome to the third post taken from Lost Civilizations of the Stone Age by Richard Rudgley. Call this the writing edition. This post hits the highlights of Rudgley’s chapters 4 and 5, pages 58 through 85.

Nah, Ancient People Didn’t Write, They were Barbarians!

The idea of writing as an exception in human history has become dogma: