Trigger warning: statue of a naked fat lady

This post is the second in a series of posts based on chapters from this book:

As Rudgley writes in the Introduction:

In this book I will show … how great is the debt of historical societies to their prehistoric counterparts in all spheres of cultural life; and how civilised in many respects were those human cultures that have been reviled as savage.

Ibid, p. 1

What do you mean, “Stone Age”?

“Stone Age,” of course, sounds very ancient, and that is by design. But when Rudgley talks about the Stone Age, often the dates involved are “only” about 12,000 to 10,000 years ago (approximately the time we think that people were crossing the Land Bridge). This falls before the beginning of recorded history — we think — unless we are willing to accept local origin myths worldwide as inevitably garbled historical records. After the small amount of study I have done about the historicity of myths, of Genesis, and of the many amazing prehistoric engineering feats, I no longer think of Stone Age people as “cave men,” but rather as fully modern humans, certainly our intellectual equals and probably our superiors. For my disclaimer about the dating of archaeological sites and prehistoric events, see my last post about Rudgley, here.

The “Venuses” of Eurasia

Chapter 14 of Rudgley (pp 184 – 200) discusses the large number of small female figurines which have been found all over Europe and as far east as Siberia. These are called “Venuses,” though of course they would not have been called that by the original artists. They were being produced (if we take the dating at face value) over a period of many thousands of years.

The oldest one, according to Rudgley, dates to the Aurignacian age, about 31,000 years ago: “the Venus of Galgenburg [Austria].” It is 7 mm tall, made of a soft green stone, and is artistically sophisticated. The figure is posed as if dancing. She is bearing her weight on her left leg. The right leg is carved free of the left and braces on the base of the figure. The right arm is carved free of the body, with the hand bracing on the knee. Clearly the sculptor knew what he or she was doing when it came to posing the figure, carving free limbs that would not break off, and piercing through the material without breaking it. Since this is (by hypothesis) the oldest such figure that we have, it’s clear that we don’t have a case of an artistic tradition that started out crude and later became more advanced. (pp 192 – 194)

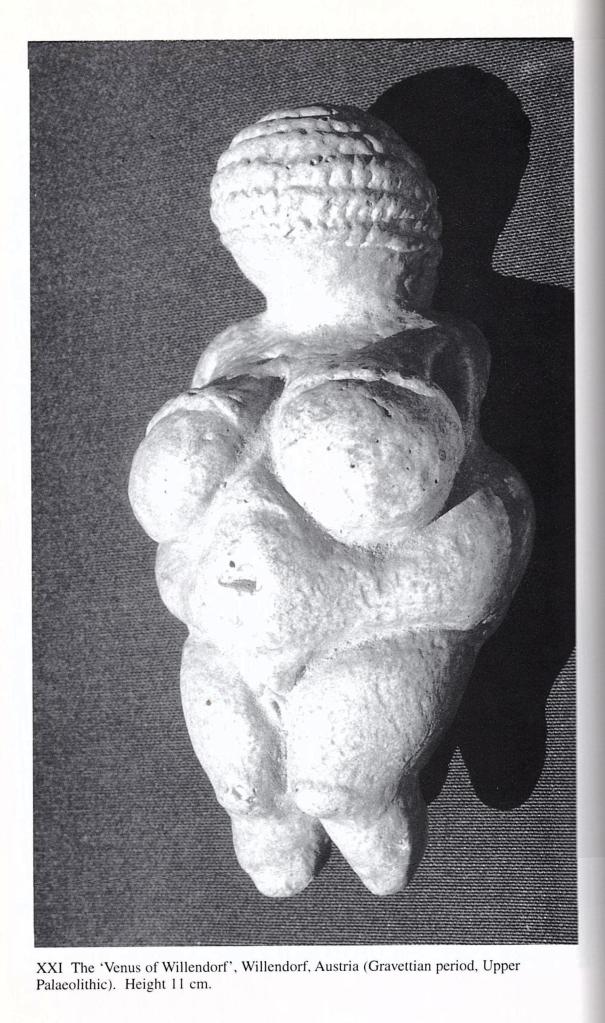

Probably the best-known of these figures is the Venus of Willendorf (also found in Austria).

When I was first exposed (pun not intended) to this little figurine, it was introduced to me simply as “the mother goddess.” Although shocking to modern eyes, it is certainly a work of art. As you can see, it has no face, but it has a considerable amount of detail in odd places such as the knees, private parts, and hairdo. The hair looks a bit like corn rows to me, but could also be braids wrapped around the head or even styled curls a la the Babylonian kings. “Alexander Marshack believes the coiffure of the Willendorf figurine may be one of the symbols of a mature and fertile woman” (198).

Not all of the Stone Age Venuses are fat or naked.

Bednarik is very skeptical about the usefulness of lumping all female figurines of the period together, noting that they are extremely diverse in numerous ways. Some are naked; others partly or fully clothed. Some are in pregnant condition; others are not. Some are fat to the point of obesity, whilst others are very slender. Beyond the fact that they all depict females and most come from the same period of the Upper Palaeolithic, they appear to have little in common.

Ibid, p. 197

The Meaning of the Venuses

Figures like the Willendorf Venus are very intriguing to some people, for obvious reasons. The explanation most ready to hand is that they are artifacts of some kind of fertility religion. This explanation is the more intuitive because of what we know about the importance that fertility often plays in pagan religions worldwide.

Marija Gimbutas has taken these figures and other evidence to posit a wide-ranging “civilization of the goddess” in Old Europe. (She published a book with that title in 1991.) She deduces (or speculates) quite a lot about this religion from Venus artifacts and from other sources. Her thesis is that the gentle, goddess-worshipping Old Europeans were overrun by warlike worshippers of a sky god coming from the Eurasian steppes (i.e. the Indo-Europeans). Gimbutas’ work had quite a strong influence on one of my high school literature teachers, who emphasized to us that worshipers of a male sky god “always” come to rape, pillage and plunder, steal, kill, and destroy. (At this point, the neo-pagans in the class would give the Christians the side eye.) We will deal with Gimbutas in another post, probably later this year.

In Jean M. Auel’s Clan of the Cave Bear books, the venuses are definitely symbols of a goddess of fertility and sexuality. Her male lead Jondalar comes from a matriarchal society in western Europe where the figurines are referred to as doni. Jondalar, when distressed, will even exclaim, “Oh, Doni!” The female lead Ayla, meanwhile, was raised by Neanderthals, who in Auel’s books severely oppress their women (because, of course, they fear their procreative power).

Moving even farther along the continuum of being obsessed with sex, Rudgley’s chapter includes a hilarious discussion of how some archaeologists have gotten over-excited and begun to interpret nearly all Palaeolithic art as porn.

It has been suggested that another important aspect of Aurignacian art was their liberal and frequent use of sexual imagery, particularly … female genitalia. This theory was first developed by l’Abbe Breuil … The idea soon caught on among French prehistorians and became something of a dogma, and various shapes engraved in stone … that looked vaguely like a vulva were automatically perceived as such by scholars eager to discover further proof of the prehistoric obsession with sexual matters. … Perhaps the most absurd example of all is a description of a simple straight line as a representation of the vaginal opening.

Ibid, pp. 194 – 195

It just cracks me up that these were French prehistorians. Of course they were. Of course.

Rudgley sums up in a way that I think is quite reasonable and balanced:

[T]he fact that the figurines are found across a huge geographical area and a period of thousands and thousands of years means that it would be ridiculous to think that they all symbolised the same thing to their extremely diverse makers. It is quite apparent that the female body was used to express numerous concerns in Palaeolithic times. [198]

We can now see how any crude explanation of the Willendorf figurine as simply a fertility figure or an object of sexual desire is entirely inadequate. The representation of the female body during the Upper Palaeolithic period … was a symbol of cosmological significance that was able to express all aspects of Palaeolithic human concerns. [199]

If the female body was one of the most widespread and elaborate images of the Old Stone Age, and a symbol for the various forces of nature and the various aspects of culture, would it really be so far from the mark to believe that the figurines actually embody aspects of the Palaeolithic worship of a goddess? [200]

Rudgley, Lost Civilizations, chapter 14

… So, Why Are They Affirming Again?

Well, obviously, on the most superficial level, the Willendorf Venus is an implied affirmation to any modern woman who is pregnant, aging, or concerned about her weight. Somebody worked very hard to portray this lady.

On a slightly deeper level, our modern culture is one that really hates the idea of motherhood. We don’t like the idea that potential motherhood is a defining characteristic of being a woman, or that it might be a worthy or even glorious goal. Unfortunately for our tidy little minds, though, motherhood (besides being a kind of superpower) is in fact a built-in goal in the design of women. Which means that knocking it as a role and calling is pretty hard on women, even those who don’t realize it, because we, as a culture, are constantly asking them, in a thousand ways large and small, if for the sake of decency they could please not exist.

In this kind of environment, it’s a tonic to know that it was not always thus. There could exist – there apparently did exist – a culture that greatly valued, perhaps even worshiped, mothers. You don’t have to be an acolyte of the goddess to appreciate the boost this gives women.

Worshiping a good thing, rather than its creator, is idolatry and idols always turn on their followers. Thus, a religion of motherhood certainly would have come with its own distortions and injustices (such as devaluing infertile women, as we see in the Old Testament). But still … it’s nice to know that at one time a mature, even obese woman was considered a thing so good that she could possibly be worshiped.

I am dealing with this topic not because I feel a particular affinity for it. I don’t enjoy looking at the Venus of Willendorf, and despite the paragraph above I would not want to look like her. I tackled these figurines because my area of interest is prehistory, and durned if they don’t show up in it. Finding out how affirming they are to women was just an unexpected bonus. And if they do feel really weird even as they are affirming, I think the weirdness comes because they are from such a different culture.