“You read people’s books, and you think you know them. They’re having a conversation with you for hundreds of pages, and there’s an intimacy there that you develop on your own. I really loved Henry McTavish. And then I got here, and the drinking, the excess, the look in his eyes as he handed me the key … Maybe now I think my picture of him was wrong.”

-Benjamin Stevenson, Everyone on this Train is a Suspect, p. 155

Tag: spiritual

Hermeticism: The Awful Truth

Sorry, folks. Life has continued to be busy. So this weekend, I’m re-posting another one of my most-often-viewed essays for your edification.

Discovering the Extent of the Problem

I learned the word Hermeticism recently.

Here’s an extended simile of what my experience was like in doing a deep dive on this word.

Imagine that your drain keeps backing up. You take a look, and discover a root. You have to find at what point the roots are coming into the pipe, so you do the roto-rooter thing. It turns out that the roots are running through the pipe all the way down to the street and across the street and into the vacant lot, where there is a huge tree.

And oh, look, it’s already pulled down the neighbor’s house!

That’s what it was like. (Oh, no! It’s in my George MacDonald pipe too!)

What Methought I Knew

I’ve listened to a number of James Lindsay podcasts, and he talks a lot about Hegel. In discussing what exactly went wrong with the train wreck that is modern education and politics, James has to dive deep into quite a few unpleasant philosophers, among them Herbert Marcuse, Jaques Derrida, Paolo Friere, and the postmodernists. And Hegel.

I had heard James describe before how Hegel saw the world. Hegel had this idea that progress is reached by opposite things colliding and out of them comes a new synthesis, and then that synthesis has to collide with its opposite and so on until perfection is reached. This process is called the dialectic. Marx took these ideas and applied them to society, where there has to be conflict and revolution, but then the new society that emerges isn’t perfect yet and so there has to be another revolution and so on until everything is perfect and/or everyone is dead.

Obviously I am simplifying a lot. James can talk about this stuff for an hour and he is simplifying too, not because these ideas are themselves complicated but because Hegel produced a huge dump of words, and he came up with terminology that tried to combine his ideas with Christian concepts so that they would be accepted in his era. Anyway, the word dialectic is still used by postmodern writers like Kimberle Crenshaw, and it is a clue that they think constant revolution is the way to bring about utopia.

So, I was familiar with Hegel through the podcasts of Lindsay, and I was also familiar enough with Gnostic thought to at least recognize it when it goes by, as it so often does. For one thing, you kind of have to learn a little bit about Gnosticism if you are a serious Christian, because gnostic (or at least pre-gnostic: Platonic, mystery religion) ideas were very much in the air in New Testament times, and many of the letters of the New Testament were written to refute these ideas. Also, Gnosticism, particularly the mind/body duality, has had such an influence on our culture that it’s hard to miss. It’s present in New Age and neopagan thought, and it’s called out in Nancy Pearcey’s book Love Thy Body for the bad effects it has had on the way we conceive of personhood.

So that’s the background.

Several months ago, I was listening to Lindsay give a talk summarizing his recent research to a church group. He was talking about theologies: systems of thought that make metaphysical and cosmological claims, and come with moral imperatives. And he dashed off this summary, something like the following:

“You could have a theology where at first all that exists is God, but He doesn’t know Himself as God, so in order to know Himself he creates all these other beings, and they are all like pieces of God but they don’t know it, and their task is to become enlightened and realize that they, too, are God, and when they realize this, eventually they will all come back together, but now God is self-conscious because of the process of breaking He’s been through.”

And I’m thinking, Sounds like Pantheism, or maybe Gnosticism.

And James says, “That’s the Hermetic theology.”

And I’ve got a new word to research.

Kind of a Weird Name

So, why is it called Hermeticism? Does it have to do with hermits?

My first foray into Internet Hermeticism immediately showed that the school of thought was named for a guy named Hermes, as in this paragraph from wiki:

Hermeticism, or Hermetism, is a label used to designate a philosophical system that is primarily based on the purported teachings of Hermes Trismegistus (a legendary Hellenistic combination of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth).[1] These teachings are contained in the various writings attributed to Hermes (the Hermetica), which were produced over a period spanning many centuries (c. 300 BCE – 1200 CE), and may be very different in content and scope.[2]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hermeticism

One of my search hits, I can’t remember which one, said that Hermeticism is “often confused with Gnosticism.” O.K., so if it’s not Gnosticism, that means I know less than I thought and it’s all the more reason to research.

I also found avowedly Hermetic web sites like Hermetic World, whose “summary” is actually more of an attempt to draw you into their movement:

Hermeticism – The secret knowledge

Hermeticism is an ancient secret doctrine that dates back to early Egypt and its innermost knowledge has always been passed on only orally. In each generation there have been some faithful souls in different countries of the world who received the light, carefully cultivated it and did not allow it to be extinguished. Thanks to these strong hearts, these fearless spirits, truth has not been lost. It was always passed on from master to disciple, from adept to neophyte from mouth to ear. The terms “hermetically sealed”, “hermetically locked”, and so on, derive from this tradition and indicate that the general public does not have access to these teachings.

Hermeticism is a key that gives people the possibility to achieve everything they desire deep in their hearts, to develop a profound understanding of life, to become capable of decision making and responsibility; and to answer the question of meaning. Hermeticism offers a hidden key to unfolding.

Nobody can teach this knowledge to himself. Even in competent books like Kybalion, the teaching is only passed on in a veiled way. It always requires a master to pass on the wisdom to the able student. Today, as in the past, authentic mystery schools are a way to acquire this knowledge. The Hermetic Academy is one of these authentic schools.

https://www.hermetic-academy.com/hermeticism/

This is certainly the genuine article, but it is perhaps not the first place to go. I wanted to learn about the basic doctrines from a neutral source, simply and clearly described. I didn’t want to have to wade through a bunch of hand-waving to get there, at least not at first. Still, I suppose we shouldn’t be surprised that Hermetic World tries to cast a mysterious, esoteric, yet somewhat self-help-y atmosphere on their first page. After all, it is a mystery religion.

Well, at least now I know why it’s called Hermeticism. It’s basically an accident of history, due to the name of the guy to whom the founding writings were attributed.

Time to move on to a book.

Moving On to a Book

I am fortunate to be descended from a scholar who has a large personal library, heavy on the theology.

I asked my dad.

Serendipitiously, he had just finished reading Michael J. McClymond’s two-volume history of Christian universalism (the doctrine that everyone is going to heaven), and he remembered that Hermeticism entered into the discussion. He was happy to lend it to me. You can see all the places I’ve marked with tabs. Those are just the ones where Hermeticism is directly mentioned. I hope you now understand my dilemma.

In McClymond’s Appendix A: Gnosis and Western Esotericism: Definitions and Lineages, I found at last the succinct, neutral summary I was looking for:

[“Hermetism”] as used by academics refers to persons, texts, ideas, and practices that are directly linked to the Corpus Hermeticum, a relatively small body of texts that appeared most likely in Egypt during the second or third centuries CE. … “Hermeticism” is often used in a wider way to refer to the general style of thinking that one finds in the Corpus Hermeticum and other works of ancient gnosis, alchemy, Kabbalah, and so forth. “Hermeticism” sometimes functions as a synonym for “esotericism.” The adjective “Hermetic” is ambiguous, since it can refer either to “Hermetism” or “Hermeticism.”

McClymond, p. 1072

O.K.

So it isn’t that different from Gnosticism after all.

“Esoteric,” by the way, means an emphasis on hidden or mystical knowledge that is not available to everyone and/or cannot be reduced to words and propositions. “Exoteric” refers to the style of theology that puts emphasis on knowledge that is public in the sense that it is written down somewhere, asserts something concrete, can be debated, etc.

Even though I have literally just found an actual definition of the word that is clear enough to put into a blog post, in the time it took me to find this definition I feel that I have already gotten a pretty good sense of what this philosophy is like. Perhaps it helps that it has pervaded many, many aspects of our culture, so I have encountered it many times before, as no doubt have you.

I began to peruse the tabs in the volumes above and read the sections there, in all their awful glory.

Yep, James Lindsay in fact did a pretty good job of explaining the core metaphysic of Hermeticism. Of course, this philosophy brings a lot of things with it that he didn’t get into. If we and all beings in the universe are all made of the same spiritual stuff as God Himself, it follows that alchemy should work (getting spiritual results with physical processes and the other way round). It follows that astrology should work (everything is connected, and the stars and men and the gods not only all influence each other, but when you get down to it are actually the same thing). It follows that reincarnation should be a thing (the body is just a shell or an illusion that is occupied by the spirit, the spark of God). It follows that there are many paths to God, since we are all manifestations of God and will all eventually return to Him/It. It follows that the body is not that important (in some versions of this philosophy, matter is actually evil). Therefore we should be able to physically heal ourselves with our minds. Our personhood should be unconnected to (some might say unfettered by) our body, such that we can be born in the wrong body, or we can change our sex or our species if we want to. There might also be bodies that don’t have souls yet (such as unborn babies), and so it would be no wrong to destroy them. Also, since matter is not really a real thing, it follows that Jesus was not really incarnated in a real human body and that He only appeared to do things like sleep, eat, suffer, and die. Also, since we are all parts of God like He is, He is not really one with God in any sense that is unique, but just more of an example of a really enlightened person who realized just how one with God He was.

I imagine that about twenty pop culture bells have gone off in your mind as you read that preceding paragraph. You might also have been reminded of the Church of Jesus Christ of the Latter-Day Saints, which teaches that we were all pre-existent souls literally fathered by God out of some sort of spiritual matter before we came to earth to be born.

So, What the Heck Is It?

Hermeticism is not just one thing. It’s a whole human tradition of thought. It had a lot of streams flowing into it, like Plato, first-century mystery religions, Gnosticism, and early attempts to reconcile Christianity with these things. It has a lot of streams flowing out of it, like many Christian mystics of varying degrees of Christian-ness; Origen; Bohme; Hegel; medieval and Renaissance alchemy; the Romantic literary movement; Mormonism; New Age thinking; identity politics; transhumanism; Shirley McLaine; The Secret, and the movie Phenomenon.

Not all of these thinkers hold to the exact same set of doctrines. In a big philosophical movement like this, almost every serious thinker is going to have his or her own specific formulation that differs from everyone else’s in ways that seem really important to people on the inside of the system. So anyone who is an insider or who has made it their life’s work to research any of the things I mention above (and many others besides) could come along and point out errors or overgeneralizations in this article and make me look like I don’t know anything. That’s partly because it’s a huge historical phenomenon and I actually don’t know much of all there is to know. It’s also partly because these mystery religions delight in making things complicated. They love to add rituals and symbols and secret names and to discover new additional deities that are personifications of abstract ideas like Wisdom. It’s supposed to be esoteric. That’s part of the fun.

Another reason it’s difficult to describe Hermeticism accurately is that when all is one, it is really difficult to talk about anything. In this view of the world, when you get right down to it there is no distinction between spirit and matter, creator and creature, man and woman, conscious and inanimate, and the list goes on. I called it Hermeticism at the beginning of this paragraph, but I was tempted to write Hermeticism/Gnosticism, or perhaps Hermeticism/Gnosticism/alchemy/mystery religions/the New Age/Pantheism/postmodernism. If you’ve ever read any New Age writers, you’ll notice that they tend to write important terms with slashes like that (“Sophia/the divine feminine”). That’s because it’s all one. They don’t want you to forget that. They don’t want to forget it. Even if these ideas do not go very well with the human mind, and they tend to break it if you keep trying to think them.

In a sense, Hermeticism and all these other related movements are very diverse and not the same at all. In another sense, it’s all … the same … crap.

Easy There, G.K.C.

It is not demonstrably unchristian to kill the rich as violators of definable justice. It is not demonstrably unchristian to crown the rich as convenient rulers of society. It is not certainly unchristian to rebel against the rich or to submit to the rich. But it is quite certainly unchristian to trust the rich, to regard the rich as more morally safe than the poor.

G.K. Chesterton, Orthodoxy, chapter 7: The Eternal Revolution

My gosh, Dickens is such a brilliant writer

Waste forces within him, and a desert all around, this man stood still on his way across a silent terrace, and saw for a moment, lying in the wilderness before him, a mirage of honorable ambition, self-denial, and perseverance. In the fair city of this vision, there were airy galleries from which the loves and graces looked upon him, gardens in which the fruits of life hung ripening, waters of Hope that sparkled in his sight. A moment, and it was gone. Climbing to a high chamber in a well of houses, he threw himself down in his clothes on a neglected bed, and its pillow was wet with wasted tears.

Sadly, sadly, the sun rose.

A Tale of Two Cities, Book II, Ch. V, “The Jackal”

How to Keep House while Drowning: A Book Review

I picked this up in the new-to-us section of the public library. This is a really well-chosen title, really lets you know what you are getting.

From the back:

If you’re struggling to stay on top of your to-do list, you probably have a good reason: anxiety, fatigue, depression, ADHD, or lack of support. For therapist KC Davis, the birth of her second child triggered a stress-mess cycle: the more behind she felt, the less motivated she was to start. …

Inside, you’ll learn to: See chores as a kindness to your future self, not a as rejection of your self-worth; Start by setting priorities; Stagger tasks so you won’t procrastinate; Clean in quick bursts within your existing daily routines; Use creative shortcuts to transform a room from messy to functional.

With KC’s help, your home will feel like a sanctuary again. It will become a place to rest, even when things aren’t finished.

I really wish that I had written this book, or that it had been written by Allie Beth Stuckey. This book, or a version of it, needs to be written by someone who understands human sin nature, grace, and the freedom that is found in Christ Jesus. It’s so, so close, but because of the author’s wokeness, there are jarring notes.

The Practical

To some, this book might sound as if it was written by a sloppy, disorganized person, to sloppy, disorganized people, to help them justify their sloppiness. On the contrary, it was written by a naturally distractible person, to distractible people, to help them achieve the level of organization that they actually want to, without letting the perfect become the enemy of the good.

KC went through rehab as a teenager. She has ADHD, is married with two small children, and is a therapist, which means that people talk to her about their frustrations with themselves and their inability to get their houses in order.

Consequently, the intended audience for this book is people who are responsible for keeping house, but have some major obstacle such as chronic pain, being in the midst of grieving, ADHD, depression, or having “issues” around cleaning due to the way they were raised … or all of the above. The goal is to help these people develop strategies to get over the mental (and sometimes physical) blocks so they can maintain their houses in basic livability. And I am there for it!

People in these situations might not have the time, energy, or attention span for a long book, so this little gem is written in short chapters, each of which gets right to the point. To accommodate people who might be very literal-minded (such as those on the autism spectrum), KC re-states all figurative language very literally. For example: “We are going to flex our motivation muscle” becomes “We are going to practice this skill until we get good at it.”

While I don’t believe that ADHD is a literal, physical brain disease, nor that it should be treated with drugs, I do believe that what we call ADHD is a good description of how some people’s minds, bodies, and sensory-processing work. And while I’ve never been diagnosed with ADHD (and have no desire to), their descriptions of how their minds work, and the strategies they use to get things done, usually sound so familiar and relatable that I find myself asking, “Doesn’t everyone experience that?” So, I could probably get a diagnosis if I wanted to. I just don’t think it would help me. I’m an older person and I’ve learned how to set up systems that work for me.

With that in mind, many of the aphorisms and strategies that KC presents here, are ones that I’ve come to myself, over years of keeping house, in season and out of season, through small children, international moves, unemployment, depression, the lot. Things like this:

- “I have a responsibility to make sure my family always have clean clothes. I don’t have a responsibility to make sure that they never have dirty clothes.”

- Any cleaning is better than no cleaning.

- Better a less efficient method or system that you can actually do, than a perfect system that never gets done.

- Doing “closing chores” the night before is a favor to your future self.

- Most people don’t have a motivation problem (since they do actually want to be able to do the task and enjoy the clean result). Instead, they have a task-initiation problem.

- And the like.

The Spiritual

Of course, there is not a firm frontier between the practical and the spiritual in our everyday lives. As Solzhenitsyn has said, the line between good and evil runs “through every human heart.” Which means that, even as we face mundane choices like do I do the dishes, the laundry, or take a nap, we are interacting with issues of bondage to sin versus freedom, and grace versus shame. So it’s not really possible to talk about practical things like task initiation without also addressing the spiritual.

KC does a pretty good job of this in her book. She starts out by saying (page 11), and this is in bold, “Care tasks are morally neutral. Being good or bad at them has nothing to do with being a good person, parent, man, woman, spouse, friend. Literally nothing. You are not a failure because you can’t keep up with laundry. Laundry is morally neutral.”

Now, since I can hear howls of objection, let me address this. What she is trying to express here, is that shame does not energize people. It paralyzes them.

Yes, moms do have a duty to keep on top of the laundry cycle and yes, (contra KC Davis), there IS such a thing as laziness, and laziness IS sinful.

But when it comes to “care tasks,” many people (most people?) grew up being shamed not for character flaws such as laziness, but for lack of technical skills in the tasks, for not doing them up to an adult’s standard, for not doing them perfectly, or for not knowing where to start. Consequently, many (most?) people have a huge burden of shame and failure around household tasks. And this burden of shame, and this perfectionism, makes it much, much more difficult to get these tasks accomplished (or in some cases even started). See? KC is not saying, “Let’s get rid of the shame because it is 100% OK to never clean your kitchen.” She is saying, “Let’s get rid of the shame associated with these tasks because only then will you be able to do them.”

In other words, KC in her self-examination and her work as a therapist has stumbled upon that biblical truth: “the law kills, but the Spirit gives life.” The only people who are free to act and move in this world are those who are not paralyzed by shame.

It’s at this point that I wish this book had been written by a Christian, because this point really deserves to be developed further. How does one set others free from shame? Certainly, if people have indeed been shamed over things that are morally neutral (such as being slow at doing chores, or doing the dishes a different way than your parent), then this needs to be clarified. But this is not enough, because not all our shame is spurious. We actually are sinners, and we actually do know it. It is not enough to say, as KC says, “I don’t think there is any such thing as laziness.” Even when we have gotten rid of the spurious shame over morally neutral things like being naturally untidy, even if your particular client is not actually lazy … what about the other shame? What are we going to do about that?

In other words, the only way that people can truly be set free from shame is when they turn to Jesus, the living Christ, who alone has the power to free us from shame, so that we can “do the good works that He prepared in advance for us to do.” I think Allie Beth Stuckey could do a lot with this. In fact, I’d love it if she were to have KC Davis on her podcast.

But then, she proceeds to shoot herself in the foot

The other problem I have with this book is as follows. For the most part, KC does a great job of being gentle with her readers and treating them like responsible human beings. But every so often, she turns around and sucker-punches them with identity politics.

Many self-help gurus overattribute their success to their own hard work without any regard to the physical, mental, or economic privileges they hold. You can see this when a thin, white, rich self-help influencer posts “Choose Joy” on her Instagram with a caption that tells us all joy is a choice. Her belief that the decision to be a positive person was the key to her joyful life reveals she really does not grasp just how much of her success is due to privileges beyond her control.

pp. 14 – 16

It’s hard to know where to start with this paragraph. Does KC really think that a “thin, rich, white influencer” posts “Choose Joy” because she is already joyful? That such people have no insecurities or struggles? That all that is necessary for joy is having circumstances line up in your life such that you avoid three major conditions which the Identity Crowd considers to be disadvantages? This is so dehumanizing as to beggar belief.

I’m not saying “Choose Joy” is advice that would be helpful to anyone, really, but I at least recognize that most people who say things like “Choose Joy” obviously mean “Choose joy in spite of all the awful things that are happening in your life.” If people are happy, at peace, and free from shame or struggle, they don’t go around saying stuff like “choose joy.” And based on the practical wisdom in the rest of her book, I think KC actually knows this. But, blinded by identity politics, she considers it OK to lay aside what she knows and take a swipe at some of her readers in a misguided attempt to build up others of her readers. Unfortunately, this undercuts her message that she doesn’t want to shame anyone. You see, this book is not for you if you are rich, thin, or especially, white. And as we know, those always go together.

In the very next paragraph, KC says what she was actually trying to say, but in a much more sane and humane way, namely that different things work for different people:

Different people struggle differently — and privilege isn’t the only difference. Someone might find a way to meal plan, or exercise, or organize their pantry that revolutionizes their life. But the solutions that work for them are highly dependent on only their unique barriers but also their strengths, personality, and interests.

p. 16

Really, that paragraph would have been sufficient, excepting the word privilege. I do wish people would stop using the word privilege — which is a legal term — when what they actually mean is “advantage.” But that’s a rant for another day.

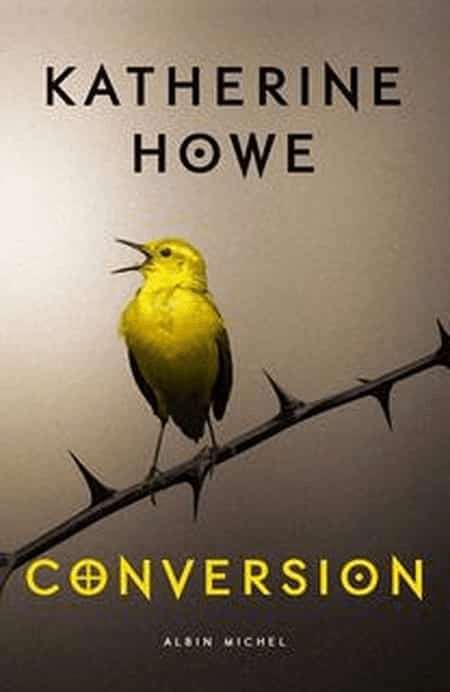

Conversion: A Book Review

My vision is crowded with whispers and movement and strange shapes narrowing in. I feel my heart thudding in my chest, the sweat flowing freely in my hair, under my arms.

Something inside me breaks. I close my eyes and open my mouth, and a piercing scream tears out of me. The scream relieves the pressure in my head, and it feels so good that I scream again.

“It’s there!” I jabber, lurching in my seat. “I see it there! Goody Corey’s yellow bird sits on Reverend Lawson’s hat! I see it plain as day, the Devil’s yellow bird sits on the Reverend’s hat!”

Conversion, p. 362 – 363

I picked up this book from the public library, among a few others, to have fiction to read over Christmas break. After one false start (a high-school drama that was unable to hold my attention), I cracked open Conversion, and it was a winner.

Here’s the blurb from Howe’s website:

A chilling mystery based on true events, from New York Times bestselling author Katherine Howe.

It’s senior year, and St. Joan’s Academy is a pressure cooker. Grades, college applications, boys’ texts: Through it all, Colleen Rowley and her friends keep it together. Until the school’s queen bee suddenly falls into uncontrollable tics in the middle of class.The mystery illness spreads to the school’s popular clique, then more students and symptoms follow: seizures, hair loss, violent coughing fits. St. Joan’s buzzes with rumor; rumor erupts into full-blown panic.

Everyone scrambles to find something, or someone, to blame. Pollution? Stress? Are the girls faking? Only Colleen—who’s been reading The Crucible for extra credit—comes to realize what nobody else has: Danvers was once Salem Village, where another group of girls suffered from a similarly bizarre epidemic three centuries ago . . .Inspired by true events—from seventeenth-century colonial life to the halls of a modern-day high school—Conversion casts a spell.

The story goes back and forth between modern St. Joan’s and 17th-century Salem. The excerpts from Salem are fairly long. I would say they take up a quarter to a third of the book. The Salem storyline is told from the perspective of Ann Putnam, one of the “afflicted” girls who, years later, made a public apology which stated that she now thought the people accused of witchcraft had been innocent.

Coming into this, I wasn’t sure I would finish it. Books about the Salem witch frenzy, after all, can easily go sideways into facile Christianity / patriarchy bashing. And at first, it did look like Howe was implying that: It’s suh-sigh-uh-tee! These girls had no pow-er! Some of them were servants! The first person they accused was a slave! However, Howe never veered into caricatures. She painted a fairly complex picture, held the girls also responsible, and the writing was good enough that I ended up finishing the book.

I do think Howe’s interpretation of what went down would be more feminist than my own. In the Salem scenes, the men are, to a person, cold, harsh, and uncaring as fathers. (Also, the women can’t read.) However, in the Danvers scenes, Colleen has loving, involved parents who are still married, a kindly younger brother, an apparently goodhearted boyfriend, and a priest at her school who seems like a good egg. The pressure on the Danvers girls comes more in the form of an academically competitive environment where they are all hoping to get into Ivy League colleges. In fact, the fact that none of the girls’ parents seem to be divorced is striking.

Spoiler Town

Howe’s diagnosis of the St. Joan’s girls – and, apparently, of the Salem girls also – is a medical phenomenon called conversion, whereby intense mental stress is “converted” into bizarre physical symptoms.

In the case of the Salem girls, as Howe tells it, it begins with one little girl who genuinely takes sick with what used to be called a nervous breakdown. It’s implied, but never drawn out, that she has been abused by her father. The phenomenon is then taken up by a servant girl living in the same house who is clearly faking at first, for attention and to get out of being worked hard. She even bites herself on the arm to manifest mysterious wounds. The phenomenon then spreads through a combination of this particular girl enjoying the attention; other girls being unwilling to speak up but just saying what they think the adults want to hear; possible suggestion as the girls work themselves into a genuine state; and simmering resentments in the town, as the girls and their parents use the trials to get revenge on those they envy.

In the case of the St. Joan’s girls, Howe is able to offer medical explanations for even the most bizarre physical phenomena. For example, one girl who has been coughing up pins turns out to have pica (a mineral deficiency that causes a compulsion to eat things that are not food, such as dirt). You see, there is a medical explanation for everything!

This book was published in 2014 and the modern-day story is set in 2012. Now, since the Plandemic, Howe’s trust of the medical establishment struck me as naive and dated. The Department of Public Health is the voice of sanity in the St. Joan’s hysteria, and it’s they who figure out that conversion (not the HPV vaccine or environmental pollution) is what’s causing it. Near the end of the book, when the phenomenon has been taken care of by these experts, Colleen narrates that “We are all on the same antidepressant.” This is a red flag to anyone who’s familiar with the research about how harmful behavioral meds can be to kids and teenagers, and how they have been chronically overprescribed, often for way too long at a time, and what a huge moneymaker they are for pharmaceutical companies. I have only a very basic, passing familiarity with this stuff, and even I was concerned. But Howe seems to believe in The Science just as firmly as the Puritains believed in The Devil.

Nevertheless, Howe draws back from explaining away the strange phenomena completely. There’s an odd scene near the end of the book when Colleen’s best friend’s mother, who is always described as pale blonde, ghostly, suffering from migraines, and almost never leaving her house, pulls Colleen into a dark corner and whispers creepily that her daughter is “like me.”

“She’s prone to spells. But it can be managed. Helps to have the family close by. I’m only telling you so you don’t have to worry.”

My mouth went dry.

“But how did you –” I stopped, because it almost seemed as though her eyes were glowing faintly red.

“Anyhow,” Mrs. Blackburn said, her smile widening, a tooth glinting in the darkness under the stairs, “They said what caused it, in the news. Didn’t they.”

“Y — yes.” I swallowed.

“Good. So there’s no problem.”

The hand released my wrist.

ibid, p. 393

I’m not sure what the purpose of this creepy scene is. Is Howe trying to buy back the “mystery” element of her book, even though by that point in the story, all the explanations have been offered? If she is trying to keep the story somewhat paranormal, I’d say the attempt is not successful. Nothing else that happens in the book, not even the scenes in Salem, hint that any actual paranormal activity might be going on. It is all just the girls’ minds deteriorating. Or is Howe trying to imply that Mrs. Blackburn is displaying Munchhausen by Proxy and is somehow making her own daughter sick? If that’s the theory, it’s way too late in the novel to introduce it, and it never gets further explored. There does seem to be a longer version of this book (“not condensed”) out there. Perhaps the Mystery of Mrs. Blackburn is explained in the longer version, but in the book I read, it just comes off like the author wants to add complexity even though she clearly believes the Harmless Medical/Societal Pressure Explanation.

When Witchcraft Was a Thing

I do not know enough about the Salem witch trials — or witch trials in general — or even the Puritains, although I have read some of them — to speak authoritatively about the degree to which Howe’s explanations are correct. Howe has done a lot of research about the Salem trials, and even includes long excerpts from the transcripts in her novel. It’s not clear, however, whether she has done much research about other witch trials in New England (or Old England), or about Puritan theological beliefs.

Fortunately, I have a book by someone who has.

When you read a lot, serendipities sometimes happen. I bought this book many, many years ago, at a used book shop in Kansas City, when I was there for a vacation with extended family. My dad has Used Bookstore Radar, and he always likes to visit the used bookstores whenever he is in a strange city. So I went with him and bought my own armload. This book was an impulse buy that survived several rounds of elimination, because Salem was one of those historical topics that I “really needed to learn more about.” Well, now the time has come.

John Putnam Demos, interestingly, found out only after he had begun witchcraft research that he is descended from the Putnams, the family who were instrumental in many of the witchcraft convictions in Salem.

I’ve only begun the book, but here is what I can tell you. Although Salem has become famous for cases getting out of hand, witchcraft (“entertaining Satan”) was a recognized crime during the 1600s, on both sides of the Atlantic. As with other crimes under English common law, any accusation had to be first investigated informally, and many of these were settled without going to court, which means we have no official records of them. If the stage of going to court was reached, there were still legal proceedings, evidence presented, and so forth, and the magistrates could and often did acquit the accused or void the case on a technicality. People who had been accused of witchcraft could also sue their accuser for slander. Some countries, and some regions of each country, prosecuted people for witchcraft far more often than others.

It is this background of which Demos wants to draw a detailed picture. He tells us that he is going to look at the biographical details of certain accused and accusers. He is going to look at this from a sociological, psychological, and historical point of view. I am sure I will learn a lot from him. But, when it comes right down it, Demos is still studying witch trials as a sociological phenomenon. He is not examining whether the paranormal may have played an actual role.

The Dominant Narrative

Possibly the most annoying scene in Conversion is when Colleen’s teacher, Ms. Slater, tells Colleen that a good historian should “look beyond the dominant narrative” about Salem. I’m not certain what Slater thinks the “dominant narrative” about the Salem witch trials is. Surely, in modern times, most people see nothing more than a story of injustice and superstition played out in an overly rigid, hierarchical society. That’s certainly not the narrative that was dominating in Salem at the time. The only way I can detect that Slater’s preferred emphasis differs from the dominant modern narrative, is that she wants us to have more sympathy for the teenaged girls who were doing the accusing, for the pressure they were probably under.

This is actually a new thought. If I may speak from my own experience, when we read accounts of the trials, the girls definitely come off as the villains of the piece: screaming accusations, making their adult victims cry. The tendency is to attribute malice. I wouldn’t say that comes from listening to a narrative told by people in power, though; rather, it’s the immediate first impression that we get from just observing their behavior.

By contrast, here’s how Ann Putnam’s experience went down in Conversion:

“Oh, Annie, tell them how we suffer!” Abigail beseeches me.

“I … I …” I stumble over my words, terrified. If I continue the lie, I’m sinning in the eyes of God. A vile, hell-sending sin. If I speak the truth, I’ll be beaten sure, and all the other girls will, too. My mouth goes dry, and bile rises in my throat.

At length, I whisper, “I cannot say whose shape it is.”

page 221

And here:

I’m beginning to panic, and I want to get up and run away [from the courthouse] and hide in the barn behind our house, but everyone is there and everyone is watching me, and my father is there and I have to stay strong and do what they want me to, and so I stay where I am, making myself small on the pew, and soon enough the tears are springing from my eyes, too.

page 258

The picture here is of a girl trapped in a story she knows there is something wrong with, but afraid to out her friends and to displease the adults. This is also very plausible. It reminds me of so-called “trans” children, trapped in an even more harmful delusion foisted upon them by the adults in their lives and by their peers, manipulated into believing this is what they themselves want and have chosen. This could have been one of many factors operating in Salem. This is how social contagions work. There is a big lie; there are vulnerable, confused children or teenagers; there are culpable adults and confused adults; there is social pressure; there is mass deception.

Multiple Causes

So let’s look at some factors, remembering that many things can be true at once.

- Hysterical Teenaged Girls: Teen and pre-teen girls tend to be stressed out in every society. Their bodies are changing, they are noticing boys, hormones are making them nervous and emotional and edgy. No, they don’t have much social power, but we need to consider whether it is actually a good idea to give teen girls a lot of social power. I think most girls hate themselves at thirteen (the age of Ann Putnam when the story takes place). Teen girls are also known to be susceptible to fads, suggestion, and yes, physical symptoms of stress. The fact that they are not very mentally stable is not an indictment of them or even necessarily of their society; it’s more of a fact that we all have to deal with. This is also the age when, unless guided, girls develop an interest in the occult. So yes, it does seem very natural that the accusers at Salem should have been a bunch of teen girls, and it’s very believable that they were not just “faking,” but had worked themselves into an actual altered state. This created a perfect storm at Salem, because the evidence to be examined a witch trial generally consisted of eyewitness testimony. These were not very reliable witnesses. But the fact that teen girls’ testimony was accepted as evidence actually argues against Salem being a sexist hellhole.

- Vengeance / Scapegoating: Already in Demos’ book, it has become evident that people who got accused of witchcraft tended to be those who had annoyed their neighbors in some way. Maybe they were the sort of person who is always arguing with everyone, or maybe they were upper-class or especially pious and so the target of envy. It’s pretty clear, even to someone not deeply familiar with the records, that accusers saw in a witch trial a way to get revenge on someone who they had perceived wronged them. Envy, resentment, and scapegoating are actually very common in human life, especially in village settings (say as opposed to city settings). If the culture in question believes in magic, then people are likely to suspect their enemies of sabotage by magic, in whatever magical idiom is local to the culture. People find it hard to accept that things can just go wrong for them. They prefer to blame someone when something goes wrong.

- Superstition: If by “Superstition” we mean “There’s no such thing as witchcraft,” then we will get to that in a moment. But if by superstition we mean, “If the New Englanders had not believed in witchcraft, the injustice of the Salem witch trials would never have happened,” then that is manifestly untrue. Of course, they would not have happened in the same way. But what scares us about Salem is not the suggestion of the paranormal so much as the purge-like quality of the proceedings, where an accusation is tantamount to a conviction, and it’s impossible for the accused to prove their innocence. Something has gone wrong with way rules of evidence are applied. A moment’s reflection will show that it is completely possible to conduct a purge in the absence of belief in witchcraft. Purges have been conducted on charges of capitalism, communism, being a heretic, being a Christian, sympathizing with the enemy in wartime, abusing children in daycare centers, date rape on college campuses, racism, not taking the government vaccine, and being insufficiently supportive of the trans agenda. If the purge mentality is present, then any superstition will do. That’s why it is foolish for us to feel superior to the Salem townspeople, as if, not being Puritans, we could never be subject to this common human practice.

- Medical Causes: I have heard theories that there may have been some physical factor, such as a particular kind of mold in their diet, that caused the girls to develop delusions and hallucinations. This seems to me like a modern materialist grasping at straws. We don’t want to believe that a bunch of teenaged girls could be so wicked as to deliberately send their neighbors to their deaths, and we certainly don’t want to consider the paranormal as a real possibility, so it must be the mold. It’s true that certain medical conditions can cause irrational behavior (even heat stroke or fever can do it), because we are embodied people. However, in a case like that I wouldn’t expect the affliction to spread like a fad among just the teen girls in a community … the very ones who are vulnerable to delusions and drama for a bunch of other reasons already covered.

- Actual Occult Activity: Not being a strict materialist, I can’t rule this possibility out. Modern Western materialists don’t believe that a spiritual world exists at all, so when it comes to interpreting things that happened in the past, we have some blind spots. We are quick to accuse people who we know to be otherwise intelligent of making ridiculous things up out of whole cloth, or of believing ridiculous things completely without evidence. But it is actually possible that there was a lot more paranormal activity in the past than now. Paranormal activity tends to manifest itself in forms that make sense to the culture where it is manifesting; so, people in Ireland have encounters with fairies, American Indians might encounter the Windigo, and modern Americans are more likely to be abducted by aliens. This doesn’t mean that nothing spiritual is going on, just that malevolent spiritual forces know how to make themselves intelligible to humans. If we accept that there was actual paranormal (dare I say, demonic) activity happening in Salem, this does not mean that we have to accept that every person who was accused – or even every person who confessed – was in fact a witch in league with the devil. There have been cases before where people confessed to things they didn’t do, because they were worn down by interrogation, eager to please, or easily manipulated. However, there could have been some people practicing the occult in Salem. The girls themselves could have gotten involved in some occult practice, which could have left them open to demonization. And in fact, even if their symptoms were entirely faked, the kind of mob/purge mentality that they displayed is always the work of the devil in the sense of being the fruit of envy, deception, and a false ideology. When people get involved in occult practice or philosophy, one tragic result is often that they lose their ability to think clearly. That certainly seems to have happened in Salem, in some form or other. The devil certainly got a lot of publicity during those months, and I’m sure he was loving it.

Guys, My Oldest Is 16

Here he is enjoying sushi on his 16th birthday.

I love this photo because it captures something about him … nerdy, techy, fit, into all things Japanese.

I also love the gritty urban look of this photo.

Naturally, I had to edit it so that his image is blurred and his privacy somewhat protected. (Guess who helped me find out where I could edit it? That’s right)

The other cool thing is this: We live in rural southeastern Idaho. You would think, all that’s available to eat out here is prickly pear, river fish, beef, and potatoes. But no, thanks to the fact that we live in this once-great empire that is falling into ruins but is still incredibly wealthy, we can drive less than an hour and get sushi. In Idaho. As this new year begins, that’s something I’m thankful for. Such convenience and prosperity certainly make it easier to raise this lovely young man. Who is, of course, another gift for which I’m incredibly thankful.

Enjoy the Stuff: New Year’s Advice from Doug Wilson

“And Jesus answered and said, ‘Verily, I say unto you, There is no man that hath left house, or brethren, or sisters, or father, or mother, or wife, or children, or lands, for my sake, and the gospel’s, but he shall receive an hundredfold now in this time, houses, and brethren, and sisters, and mothers, and children, and lands, with persecutions; and in the world to come eternal life” (Mark 10:29 – 30)

Now there is a certain kind of compromised Christian for whom the first part of this passage (v. 29) is the “hard saying.” The cares of this world do choke out spiritual interest. But there is another kind of Christian, the pious, otherworldly kind, for whom the hard saying is actually found in v. 30. It is as hard to give house and lands to some Christians as it is to take them away from others.

Imagine a glorious mansion on one hundred acres on a scenic stretch of the Oregon coast, and then imagine yourself having been assigned the task of giving it to an otherworldly prayer warrior. The Lord wanted him to be in a position to paint some glorious water colors, but only after conducting his prayer walks on the beach. He nevertheless was struggling with the whole concept because the guilt made it difficult to hold the brush.

The challenge is this: how can we hold things in the palm of our hand without those things themselves growing hands that can hold us in a death grip? The Lord promised that we could handle serpents and not be bitten (Mark 16:18), and mammon is certainly one of those serpents.

American Milk and Honey, pp. 151 – 153

A Very Sane UFOlogist

Gary Bates, interviewed by Jon Harris on Conversations That Matter, is the most sane and humane UFOlogist you could hope to meet.