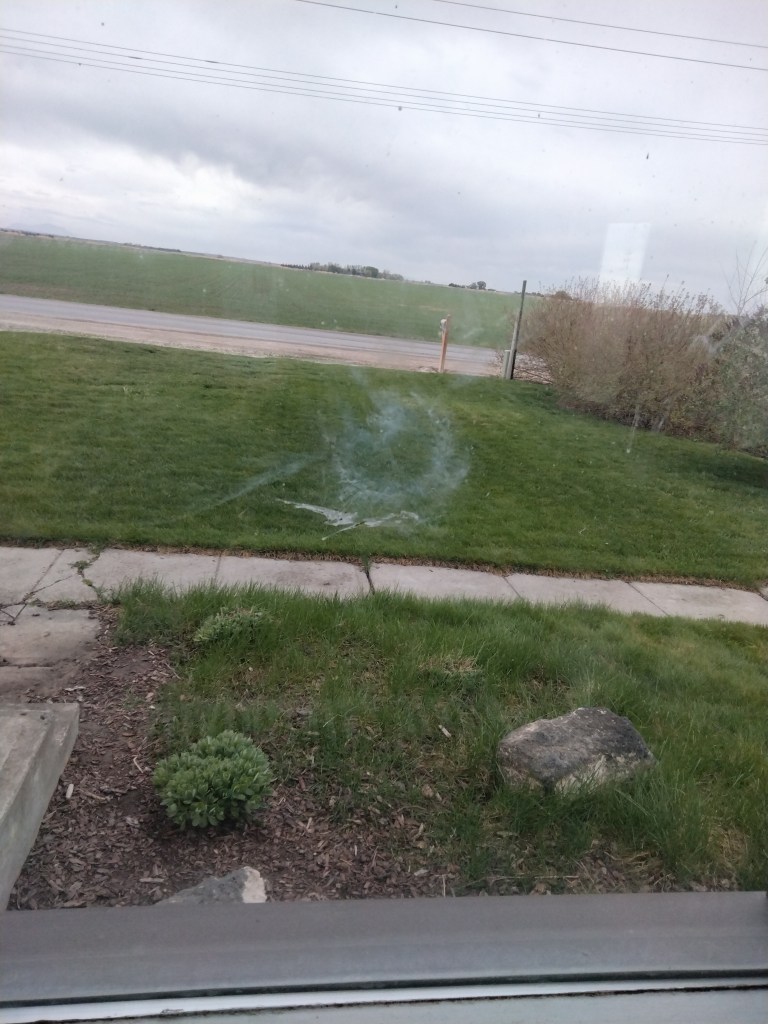

I photographed this stuff growing, as you see, in/near a stream near the Hiawatha Bike Trail in northern Idaho. N.b.: the taller, thicker plants in the immediate foreground are not the same ones I am talking about. I am focused on the feathery, jointed ones near the stream.

Using my Central Rocky Mountain Wildflowers guidebook and the Internet, here is a list of possible identifications I considered:

- star gentian

- red mountain heather or yellow mountain heather. One problem with these two is they seem to prefer dry, sunny spots. Another problem is that their leaves are likely too thick to match.

- swamp laurel. This is still a good candidate, as it prefers wet spots and, though native to eastern North America, also is said to live in “Montana.”

- perhaps the young version of some variety of Indian Paintbrush plant. The problem, again, is that they seem to prefer dry, sunny areas.

- rough wallflower. Problem: “found on open, lightly wooded slopes.”

Then I broke down and asked Google to examine the photo, which means, like it or not, I was enlisting the help of AI. Here were Google’s two suggestions:

- Amsonia hubruchtii or

- Bassia scoparia a.k.a. Summer Cyprus or Burning Bush.

Bassia scoparia is our best candidate, and here’s why. It can be found in “riparian areas,” according to the article that I linked. “It naturalizes and self-seed easily.” “This plant is a noxious weed in several states.”

Edit: Beth has suggested it may be “horsetail,” Equisetum arvense. I looked it up, and Horsetail is the most likely candidate yet! According to Wikipedia,

Equisetum arvense, the field horsetail or common horsetail, is an herbaceous perennial plant in the Equisetidae (horsetails) sub-class, native throughout the arctic and temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere. … Many species of horsetail have been described and subsequently synonymized with E. arvense. One of these is E. calderi, a small form described from Arctic North America.

Northern Idaho isn’t exactly Arctic, but it’s gettin’ close.