Q: When is a good time to start mocking the prophets of Baal?

A: Around noon.

Q: What time is it now?

A: 4 p.m.

Q: When is a good time to start mocking the prophets of Baal?

A: Around noon.

Q: What time is it now?

A: 4 p.m.

Here I am, using my color vision to spot the ripest raspberries in the thicket. Darker ones are ready. I can distinguish fine grades of color.

Then, I use my specially designed opposable thumbs to pick the ripest raspberries. My fingers have been given the ability to sense, and calibrate their grip for, the finest gradations of pressure. This allows me to pull each berry off its core without squishing it. Most of the time.

The raspberries, for their part, have been specially designed to be picked and eaten by me. Every year, they produce a ridiculous bumper crop. “Pick us!” they groan. They have been given thorns, of course, but these are at best a halfhearted attempt to fight back. All I need to do is put on a long-sleeved shirt, and the prospect of a nasty scratch is no match for the motivation furnished by the berries’ taste.

The raspberry bushes are very good at surplus. They produce far more berries than I can realistically pick, and they hide them where I will never find them all.

They taste sweet-tart. They provide fiber and Vitamin C and I don’t know what all. They look so pretty paired with yogurt and oatmeal on a summer morning.

This morning while I was deep in the raspberry patch, my son picked up one of our chickens and at that moment she laid, the egg dropping from his arms to the ground. It didn’t break. Food was literally falling from the sky.

Over the past several years, my research and reading has led me more and more to the conviction that the entities that people often call the old gods were not “mere mythology.” They were and are real.

Several threads of my thinking have re-enforced each other in coming to this conclusion.

First of all, as a Christian, I reject the Enlightenment-era, materialist notion that there is no spiritual world, that matter is all that really exists. I reject both the strong version of this, in which not even the human mind is real, and the weak version of it, in which we accept that human beings exist as minds, but we try envision as them as “arising” out of matter, and we disbelieve in any other spiritual beings, whether spirits, angels, demons, ghosts, or the one true God. This view, the one I reject, has held sway for most of our lifetimes. Even people such as myself who would not call themselves materialists will lapse into this sort of thinking by default, looking for a physical or mechanical process to explain what is “really” going on behind any claimed spiritual phenomenon.

Another thread in the tapestry has been my interest in the ancient world. Anyone with a passing familiarity with archaeology quickly comes to realize that ancient people were much smarter than they have gotten credit for, at least during the Golden Age of Scientific Triumphalism, the late 1800s and early 1900s. All the good, old-fashioned scientific materialists from this era took it as an axiom that human beings started out as apelike hunter-gatherers, and slowly “ascended,” developing shelter and clothing, “discovering” fire, slowly and painfully inventing various “primitive” tools, and then finally moving on to farming, language, and religion. By hypothesis, ancient people were stupid compared to us now.

Genesis, my favorite history book, tells a very different story. It shows people being fully human from the get-go, immediately launching into writing, herding, weaving, art, music, and founding cities. And in fact, archaeology confirms this. Every year, we discover a more ancient civilization than the evolutionists told us existed. Some recent examples: the Antikythera mechanism is an ancient computer. The Vinca signs are an alphabet that pre-dates Sumeria. Gobekli Tepe is a temple complex that uses equilateral triangles and pi, and dates to “before agriculture was invented” (as is still being claimed). The Amazon basin turns out to have been once covered in cities.

Evolutionists’ dogmatism about early man being stupid has allowed them to ignore all the data that ancient history presents us about the existence of a spirit world. Why should we believe claims (universally attested) about heavenly beings that come to earth to visit, rule over, and even mate with humans? These are primitive people’s attempts to explain purely scientific phenomena that they didn’t understand. But if, as a Christian, I choose to respect ancient people and take seriously their intelligence, then I also have to grapple with their historical and cosmological claims.

Moving on to the third thread. The Bible itself confirms that there were entities called gods (“elohim”), some of whom, at one point in very ancient times, actually came to earth and reproduced with human women, creating a race of preternatural giants, “the heroes of old, men of renown” (Gen. 6:4). The story is told in Genesis ch. 6, but it is assumed and referenced throughout the rest of the Bible and in Hebrew cosmology. This idea is also attested in oral and written traditions worldwide, which universally have gods and giants. A Bible-believing Christian can take seriously the bulk of pagan history, cosmology and myth, whereas a strict materialist evolutionist has to reject it all as primitive superstition.

Two books that have helped me understand Genesis 6 and how it fits into Ancient Near Eastern cosmology were The Unseen Realm by Michael Heiser and Giants: Sons of the Gods by Douglas Van Dorn. I’ve also had conversations with Jason McLean and enjoyed listening to The Haunted Cosmos podcast. The historical record about gods and giants, once forgotten by mainstream Christians in America, is again becoming a topic of interest in the evangelical world.

Part of the Biblical understanding of the gods is that they are created entities who were supposed to help the one true God rule the cosmos. In the course of redemption history, the fallen gods were first banished from appearing physically on earth (in the Flood). At Babel, the gods were each given a nation of men as their “portion” to rule over (Deut. 32:7 – 8), which they did a pretty poor job (Psalm 82). Then God called Abram to make a people for Himself, with the ultimate goal of making all the nations His portion (Ps. 82:8, Ps. 2, Matt. 4:8 – 9). When Christ came, He began to drive the gods out of their long-held territories (Mat. 12:28 – 29). Whenever a region was Christianized, the old gods would first fight back, then become less powerful, and eventually go away altogether. Sometimes, their very names were forgotten. This disappearance of lesser spiritual entities from more and more corners of the earth is the only reason any person could ever seriously have asserted that there is no spirit world.

As a Christian, I am immensely grateful to have grown up in a civilization from which the old gods had been driven. It has been a mostly sane civilization, in which everyday life is not characterized by spooks, curses, possession, temple prostitution or human sacrifice.

This, then, is the background that I brought to Cahn’s book. This mental background helped me to accept many of his premises immediately. If you do not have this background – if you are, for example, a modern evangelical Christian but still a functional materialist – Cahn’s book might be a bit challenging. He dives into the deep end right away. He moves fast and covers a lot of material.

In his own words,

Jonathan Cahn caused a worldwide stir with the release of the New York Times best seller The Harbinger and his subsequent New York Times best sellers.

n.b.: I had seen The Harbinger on sale, but I assumed it was fiction in the style of the Left Behind series and avoided it.

He is known as a prophetic voice to our times and for the opening up of the deep mysteries of God. Jonathan leads Hope of the World … and Beth Israel/the Jerusalem Center, his ministry base and worship center in Wayne, New Jersey, just outside New York City.

To get in touch, to receive prophetic updates, to receive free gifts from his ministry (special messages and much more), to find out about his over two thousand messages and mysteries … use the following contacts …

From page 239 of this book

In other words, Jonathan Cahn swims in the dispensational or charismatic stream of Christianity. He calls himself a prophet. That’s a red flag to me, as a Reformed Christian. I believe that the prophetic age ended with John the Baptist (Matt. 11:11 -14). The prophets and apostles were the foundation of the church, and they died out with the first generation of Christians (Eph. 2:19 – 22). This exegesis of Scripture finds confirmation in daily life. I have met Christians who sensed God speaking to them (and have experienced it myself), but I have never met anyone who claimed to be a modern-day prophet, receiving authoritative words from God, who wasn’t a charlatan.

To make matters worse, Cahn asserts that he can “open up the deep mysteries of God” and that we can “find out about his over two thousand messages and mysteries.” This is a direct claim to have exclusive spiritual knowledge that is not available to all in the already-revealed Word of God. If he were just talking about knowledge already found in the Bible, he would call it “exegesis” or “Bible teaching,” not “messages and mysteries.” This claim reveals him to be part of the Gnostic or Hermetic stream of Christianity. Yes, I am using the words “Gnostic” and “Hermetic” loosely. They are big terms with somewhat flexible definitions. However, both are characterized by an emphasis on secret or esoteric knowledge which can only be accessed through a teacher (or, in this case, a prophet) who has been enlightened somehow. To see my posts about Hermeticism and why it is it antithetical to orthodox Christianity, click here, here, here, and here.

I knew when I picked up this book that Cahn was dispensational, a “prophet,” and therefore fundamentally a false teacher. So, I approached the book not as I would an exegesis by a trusted or mostly trusted, orthodox teacher or scholar like Michael Heiser or Douglas Van Dorn, but rather with curiosity. My interest in the topic of the old gods is such that I can’t ignore what anyone claiming the name of Christ had to say about it. I already knew there was a resurgence of interest in this topic in the Reformed world, and now I wanted to see what the Dispensationalists were saying. I picked it up prepared for anything up to and including rank heresy, but as it turned out, the most heretical thing in the book was the “About Jonathan Cahn” section that I just showed you. The rest was, for someone with my cosmology, mostly pretty hard to disagree with.

Cahn spends four very short chapters (Chapters 2 – 5; pages 5 – 22) establishing the ideas I attempted to establish above: that the gods of the ancient world were real spiritual entities who ruled over nations and received their worship. He demonstrates briefly that this was assumed in the Bible and in Hebrew cosmology. He uses the word shedim, a Hebrew word for demon or unclean spirit, which is sometimes used in the Old Testament to describe the gods. He doesn’t get into the idea of elohim, Watchers, or other different names for spiritual entities, or many details of how they fell. Entire books can be (and have been) written about this (see Michael Heiser). However, Cahn wants to move on and see what is going on with these entities in the modern day.

Moving at treetop level, he reviews how the coming of Christ progressively drove the gods out of more and more regions of the earth, in a process that took centuries. He describes civilizations as being “possessed” by the gods they serve. I don’t think he means that every person in a pagan civilization is demon possessed, but as a group, their thinking and behavior is shaped and to some extent controlled by whatever god they serve. As someone who has studied the Aztecs, I can’t disagree. Cahn also points out that it was common, indeed routine, for priests, priestesses, and prophets of the pagan gods to experience actual possession, such as the Oracle of Delphi, the girl with the “python spirit” in Acts 16, or worshippers going into a “divine frenzy.”

Having introduced the concept of possession, Cahn moves on to a parable Jesus told about the dynamics of possession in an individual.

When an evil spirit comes out of a man, it goes through arid places seeking rest and does not find it. Then it says, “I will return to the house I left.” When it arrives, it finds the house unoccupied, swept clean and put in order. Then it goes and takes with it seven other spirits more wicked than itself, and they go in and live there. And the final condition of that man is worse than the first. That is how it will be with this wicked generation. Matt. 12:43 – 45, NIV

Typically of Jesus, this parable works on three levels. The house which is cleansed, left empty, and then re-occupied stands for a person who has been demon-possessed, has been delivered, and then ends up in a worse state than before. And the person, Jesus says, can stand for “this wicked generation.”

Cahn takes this parable and applies it to entire civilizations. He has already established that pagan civilizations were possessed, sometimes literally, by a variety of old gods, to their sorrow. When the Gospel came to them, Christ showed up in person, delivered and cleansed them, and lived in their house. Now, says Cahn, what might happen if a civilization rejects Christ, drives Him out? The house (the post-Christian civilization) has been “swept clean and put in order” by its centuries of Christianity, but it is now “empty,” having driven out Christ. It is now a very attractive vessel for “seven other spirits more wicked than the last.”

I honestly don’t think this is an abuse of Scripture. Cahn seems to be applying the parable in one of the senses in which Jesus meant it. Furthermore, he is not the first to point out that the many wonderful benefits of modern Western civilization are an aftereffect of about 1500 years of Christianity. Some commentators have said that “we are living off interest.” Others have compared us, as a society, to someone sawing off the branch he is sitting on. Doug Wilson has mourned that “we like apple pie, but we want to get rid of all the apple orchards.”

A post-Christian society, say Cahn and many others, for various reasons is vulnerable to much greater evils than a pre-Christian one. In the rest of the book, Cahn will show how the old gods have indeed come back. His focus is on the United States, because he’s an American, but also because the United States has a been a major exporter of culture to the world, and in recent years that culture has been of the demonic variety. Cahn’s book is so persuasive because he is not, as “prophets” often do, sketching a near-future scenario and trying to convince us of it. Instead, he is describing what has already happened.

When Cahn first started talking about “the gods” coming back, it occurred to me to wonder, “Which gods?” When Americans or Europeans become openly neo-pagan, I’ve noticed they often go for the gods their ancestors worshipped. So, many people research the Norse gods and cosplay as Vikings … except it’s not just cosplay. Other people are more attracted to the Celtic pantheon. These are the Wiccans. Interestingly, in S.M. Stirling’s Emberverse series, we have a very literal return of the gods when technology vanishes from modern society. Creative anachronists suddenly find that their skills are useful. A Wiccan busker becomes the leader of her own little witch community. Other people get into reviving the Norse religion. It’s a neopagan’s fantasy.

But there are a couple of problems with this. For one thing, neopagans’ version of the ancient religion often looks very different from the actual beliefs of the ancient pagans (many of which have been lost to history). Also, modern neopagans are happy to mix elements of different traditions from opposite sides of the globe: wicca, Tibetan Buddhism, or their kooky version of American Indian religions (probably also not very authentic). I once commented to a neopagan friend of mine (back when we were still friends) that her religion resembled a “personal scrapbook”. And she happily acknowledged this as one of its good points. A DIY paganism, popular with modern individualists, is not the sort of the thing that can become the state religion of a whole society. Finally, actual, hardcore neopagans are not small in number, but they are nowhere near the majority in the United States. Neopaganism does not appear, at this moment, to be the manner in which an entire postChristian society comes under the control of the old gods. And, in fact, that’s not exactly what Cahn has in mind.

America is not made up of any one ethnicity or people group but many, almost all. In many ways America is a composite and summation of Western civilization. So then what gods could relate not to one nation or ethnicity within Western civilization but to all of them or to Western civilization as whole? … The faith of Western civilization come from ancient Israel. The Bible consists of the writings of Israel, the psalms of Israel, the chronicles and histories of Israel, the prophecies of Israel, and the gospel of Israel. The spiritual DNA of Western civilization comes from and, in many ways, is the spiritual DNA of ancient Israel. … The gods, or spirits, that have returned to America and Western civilization are the same gods and spirits that seduced ancient Israel in the days of its apostacy. … If a civilization indwelled by Israel’s faith and word should apostacize from that faith, it would become subject to the same gods and spirits of Israel’s apostacy.

ibid, pp. 34 – 35

I have a feeling that Cahn, coming from the worldview he does, is setting up this principle as a hard-and-fast rule, and I don’t feel he has really established it as such from Scripture. However, I’m open to it as speculation. Though it’s not, in my opinion, closely argued, his line of reasoning becomes more convincing when we see the gods that he identifies as having returned to America.

He calls them the “dark trinity”:

Once these gods are identified, we can see that it does not seem so arbitrary that they should be the ones to return. For one thing, they and the God of the Israelites were personal enemies, as it were, battling for control of the same territory, for many centuries. But secondly, these pagan gods come close to being universal.

Baal is your basic male sky god. His name means “lord,” and his essence is basically that of taking power for oneself, rebelling against the Creator. Once we look at him this way, we can see that every pantheon has a Baal. In Ugarit, an ancient Semitic civilization, Baal was understood to be the Creator’s chief administrator over the earth, head of the divine council (credit: Michael Heiser). Baal was actually translated as Zeus in Greek and Jupiter in Rome.

Ishtar, a dangerous female sex goddess, shows up as Inanna in Sumer, one of the most ancient civilizations whose records we can actually read. Cahn spends much of the book delving into Inanna’s characteristics and history, for reasons that will become clear. But, through a process of cultural exchange, she showed up as Ishtar in ancient Babylon (leading to the words Ostara and Easter), Ashera among the Phoenicians (a.k.a. Canaanites), and Aphrodite among the Greeks (Venus among the Romans).

Molech was called Chemosh in Moab. Greek historian Diodorus Siculus translates his name as Kronos (Saturn), the god who devoured his own children. Many many cultures throughout the world have practiced infant sacrifice.

These three gods, then, not only show up by different names in nearly all the cultures of the Ancient Near East right down to Christian times; they not only are the types of entities that show up in nearly every pantheon worldwide, even in the Americas; they also appear to date back to ancient Sumer, which is still a source that is sought by modern neopagans and Hermetic believers. They are not, unfortunately, out of date or obscure. Suddenly, it no longer seems as if they are irrelevant to modern America.

Briefly, Cahn argues that cultures (not just America) first let in Baal, who ushers in Ishtar, who ushers in Molech. And he argues that in our culture, this has already happened.

Baal represents the motivation for rebelling against the one true God that seems reasonable. Human beings want prosperity, they want security, they want to do their own thing. They want a god who can reliably make the rain come, the crops grow, the city flourish. They want to have independent, personal power, and not have to humble themselves before or depend upon the Creator. Baal is the god of prosperity, money, and success. Cahn says that America first welcomed Baal. He points to the actual bronze statue of a bull at Wall Street as a literal, though unintentional, idol to Baal, right in the financial center of arguably the most powerful and influential city in our nation.

Once you have Baal, he ushers in his consort, Ishtar. Ishtar is a much more unstable character. As the prostitute goddess, she likes people to engage in sexual chaos. In her instantiation as Inanna, she is emotionally unstable and vengeful, notorious for taking lovers and then killing them (which is why Gilgamesh tried to turn her down). As the patron of the alehouse, she is also the goddess of beer. And she presides over the occult, and with it, drugs. So, Ishtar’s influence began to surge in the 1960s, with sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll, accompanied by a rising interest in the occult and a rising sense of rage. Cahn will have more to say about Ishtar.

Finally, Ishtar ushers in Molech. In the early 70s, after the worship of money and immediately after the Sexual Revolution, American’s highest court legalized the killing of infants. This practice has been defended with religious fervor by its followers ever since. Just as with the Phoenician worshippers of Molech, killing babies has been called not just a necessary evil but a moral good, and opposing this killing has been called a moral evil. Just as when Molech reigned in the Ancient Near East, babies have been killed in their thousands and then in their millions.

We started out just wanting to get ahead, and now here we are, in the darkest place imaginable. But unfortunately, with the gods things can always get worse.

So far, Cahn’s claims have presented themselves to me as insightful, not completely new. Adjusting for his dispensational worldview, what he says makes good sense to anyone who has a passing familiarity with the Old Testament and modern American history. To someone who has had a special interest in the ancient world, they make even more sense. Everything that he has said so far has been hard to argue with, though of course it is still a terrible sight.

Now, however, we are moving into the part of the book that caused me to put Mind: Blown in the title of this post. Cahn spends a good half of the book (pages 115 – 207, out of 240 total) delving into Inanna/Ishtar, and how precisely her characteristics map onto the social changes that have recently been taking place in the United States.

I can’t go into detail about this, but quickly, here are some characteristics of the Sumerian goddess Inanna and her cult. I’ll let you make the applications yourself:

Cahn spends nine chapters (pp. 143 – 172) arguing that the infamous Stonewall riot was, in many ways, the exact night that Ishtar battered down the gates of America. In June 1969 a crowd outside Stonewall, a gay bar in New York City, turned on the police who had raided the place. The police eventually withdrew into the bar, and the crowd, ironically, was now trying to get inside, battering at the doors and even trying to set it on fire. Symbolically, they were trying to get in, just as Inanna famously insisted on being let in to the gates of the underworld. They threw bricks, just as she stood on the brick wall of the city of Uruk to unleash her fury on the whole city because of Gilgamesh.

Cahn argues that New York City is symbolically the gateway of America. As the gay crowd battered at the door of the Stonewall bar, Inanna was simultaneously battering to be let in. As they felt enraged at not being considered mainstream, Inanna too was enraged at, for many centuries, having been driven out.

“If you do not open the gate for me to come in, I shall smash the door and shatter the bolt, I shall smash the doorpost and overturn the doors.”

Myths from Mesopotamia, quoted in ibid, p. 166

Cahn is trying to cover a lot of ground, so he goes over all this at treetop level. I particularly would like to have heard more about the details of the Sumerian sacred calendar, how it relates to the month of Tammuz celebrated by the Israelites, and how its dates in relation to the modern calendar are calculated. Cahn finds significance, for example, in the date June 26, which was the date of the Supreme Court decisions Lawrence vs. Texas (2003), which legalized homosexual behavior; United States vs. Windsor (2013), which overturned the Defense of Marriage Act, and Obergefell vs. Hodges (2015), when the rainbow was projected onto the Empire State Building, Niagara Falls, the castle at Disney World, and the White House, in a clear statement that our nation had declared it allegiance to Inanna. Cahn asserts that June 26 has significance in the commemoration of Inanna’s lover Tammuz, who was ritually mourned every year.

In 1969 the month of Tammuz, the month of Ishtar’s passion, came to its full moon on the weekend that began on June 27 and ended on June 29. It was the weekend of Stonewall. The riots began just before the full moon and continued just after it. The Stonewall riots centered on the full moon and center point of Tammuz.

ibid., p. 170

The day that sealed Stonewall and all that would come from it was June 26, 1969. It was then that deputy police inspector Seymour Pine obtained search warrant number 578. … On the ancient Mesopotamian and biblical calendar, [the warrant] took place on the tenth day of the month of Tammuz. Is there any significance to that day? There is. An ancient Babylonian text reveals it. The tenth of Tammuz is the day given to perform the spell to cause “a man to love a man.”

ibid, p. 171

This does seem really striking at first blush. Note, though, that in the typical manner of esoteric gurus, if the date June 26 doesn’t fall on exactly the beginning of the Stonewall riots, Cahn takes something significant – or that he asserts is significant – that happened on a date near by the riots, and points to that. Why are we considering the obtaining of the warrant to be the event that “sealed” the riots? Because otherwise, the dates don’t work out quite right.

The timing of the Supreme Court decision had nothing to do with the timing of Stonewall … it was determined by the schedule and functioning of the Supreme Court. And yet every event would converge within days of the others and all at the same time of year ordained for such things in the ancient calendar… So the ruling that legalized homosexuality across the nation happened to fall on the anniversary of the day Stonewall was sealed. The mystery had ordained it.

ibid., p. 203

I must say, if Graham Hancock were covering this subject, he would devote several lengthy chapters to the calendar aspect of it. Whole books have probably been written about this. It did make me want to study in more depth ancient Sumeria, with the same terrible fascination with which I have scratched the surface of studying the Aztecs and the Mayas. I’m not super good at the mathematical thinking required to correlate calendars or unpack ancient astronomy, though I do enjoy reading other people’s work.

Not being a dispensationalist, I am less concerned with exact numbers and dates being the fulfillment of very precise prophecies, and more concerned with the general, overall picture of nations turning toward or away from God. I don’t think we need the repeated date of June 26 to match up with the Sumerian calendar perfectly in order to see that America has rejected heterosexuality, and indeed the whole concept of the normal, in a fit of murderous rebellion against the Creator, and that this is entirely consistent with the spirit of this particular goddess.

Nevertheless, I have only named a few striking parallels between the Stonewall riots and the myths and cult of Inanna. Cahn weaves it into a compelling story, and hence the title of this blog post.

I’m also a little concerned with the amount of power that Cahn seems to be granting here to Inanna, and to the whole Sumerian/Babylonian sacred calendar. I have no doubt that this ancient entity would prefer to bring back her worship in the month it used to be conducted, around the summer solstice every year. I realize that every day in the Babylonian calendar was considered auspicious or inauspicious for different activities, due to the labyrinthine astrological bureaucracy that the gods had set up. No doubt, the gods would prefer to bring back as much of that headache-inducing system as possible. However, this does not mean that they are always going to get their way. It is not “ordained” in the same sense that the One God ordains things by His decretive will. He is in charge of days, times, and seasons, and of stars and solstices. He is the one who made these beings, before they went so drastically wrong.

Then Daniel praised the God of heaven and said,

“Praise be to the name of God for ever and ever; wisdom and power are His.

He changes times and seasons; he sets up kings and deposes them.

He gives wisdom to the wise and knowledge to the discerning.

He reveals deep and hidden things; He knows what lies in darkness, and light dwells with Him.”

Daniel 2:19 – 22

To his credit, Cahn, after scaring the pants off anyone who is not on board with bringing back full-on Sumerian paganism, gives a nice, clear Gospel presentation at the end of his book. His last chapter, The Other God, points his readers to Yeshua:

Even two thousand years after His coming, even in the modern world, there was still none like Him among the gods. There was none so feared and hated by them. … He was, in the modern world, as much as He had been in the ancient, the only antidote to the gods — the only answer. As it was in the ancient world, so too in the modern — in Him alone was the power to break their chains, pull down their strongholds, nullify their spells and curses, set their captives free.

ibid, p. 232

When one is trying to get into a house, one seeks openness. One pushes to open its door. So when the gods were seeking to get into the American house and that of Western civilization, the focus was on openness and tolerance. It was never really about either.

The Return of the Gods, by Jonathan Cahn, p. 219

The above book qualifies as my most mind-blowing read of the year so far (as well as I can remember). I’ll work on a review to have up by Friday.

In the meantime, the primary domain of this here Out of Babel blog is now outofbabelbooks.com (note that I have also updated the name on the banner). If you are here, congratulations, you found it!

The old url, outofbabel.com, is still in the process of being transferred to another user. Apparently, this can take a while. When the transfer is complete (perhaps by next week?), the address outofbabel dot com will no longer be associated with me in any way. At that point, some of you may see your shortcuts to my blog stop working. I don’t know. If that happens, keep calm and create a shortcut to outofbabelbooks dot com. Thank you.

What happened to the Oracle of Delphi, the pinnacle of pagan revelation and its most exalted case of spirit possession? In the year 362 the pagan Roman emperor known as Julian the Apostate attempted to restore the oracle’s temple to its former glory. He sent a representative to consult her. She sent back a word that would become known as her last pronouncement:

“Tell the emperor that my hall has fallen to the ground. Phoebus no longer has his house, nor his mantic bay nor his prophetic spring: the water has dried up.”

The Return of the Gods, p. 22

I am traveling this weekend. I’ll be going to a conference, where I hope to personally connect with the proprietors of Haunted Cosmos Podcast. These guys are (I believe) kindred spirits in that they are Reformed Christians with an interest in paranormal ancient mysteries weird stuff. If I can convince them to re-issue my books under their imprint, maybe I will be free no longer need to promote my own books and all our troubles will be over. Anyway, a lot of things are up in the air just now (at least, in my mind they are), so pray for God’s will to be done there. And in the meantime, definitely check out the Haunted Cosmos podcast.

Secondly, I have finally broken down and become a creator on Patreon. Not much happening over there yet (or maybe ever), but please do visit Out of Babel Art and Novels if you are seized with an inexplicable urge to give me money.

Finally, here is the book I’m currently reading.

Obviously, the chilling topic of the old gods and their ongoing activity in this world is one that’s near and dear to my heart. I bought this book because I wanted to see what the Dispensationalists were saying about it. So far, it’s solid and pretty hard to argue with. Here’s a quote:

Since the house is clean, swept, and in order, the spirit brings in seven other spirits to join in the repossession. The implication is that if the house had not been cleansed and set in order, the spirit would not have brought back the other spirits to occupy it.

And therein lies the warning. The house that is cleansed and put in order but remains empty will be repossessed. And if it should be repossessed, it will end up in a worse state than if it had never been cleansed. What happens when we apply this to an entire civilization? … Should a culture, a society, a nation, or a civilization be cleansed, exorcised of the gods and spirits – but then remain or become empty – it will be repossessed by the gods and spirits that once possessed it, and more. And it will end up in a far worse state than if it had never been cleansed or exorcised at all. …

A post-Christian civilization will end up in a far darker state than a pre-Christian civilization. It is no accident that the modern world and not the ancient has been responsible for unleashing the greatest evils upon the world. A pre-Christian civilization may produce a Caligula or a Nero. But a post-Christian civilization will produce a Stalin or a Hitler. A pre-Christian society may give birth to barbarity. But a post-Christian society will give birth to even darker offspring, Fascism, Communism, and Nazism. A pre-Christian nation may erect an altar of human sacrifice. But a post-Christian nation will build Auschwitz.

ibid, pp. 25 – 26

Sorry, folks. Life has continued to be busy. So this weekend, I’m re-posting another one of my most-often-viewed essays for your edification.

I learned the word Hermeticism recently.

Here’s an extended simile of what my experience was like in doing a deep dive on this word.

Imagine that your drain keeps backing up. You take a look, and discover a root. You have to find at what point the roots are coming into the pipe, so you do the roto-rooter thing. It turns out that the roots are running through the pipe all the way down to the street and across the street and into the vacant lot, where there is a huge tree.

And oh, look, it’s already pulled down the neighbor’s house!

That’s what it was like. (Oh, no! It’s in my George MacDonald pipe too!)

I’ve listened to a number of James Lindsay podcasts, and he talks a lot about Hegel. In discussing what exactly went wrong with the train wreck that is modern education and politics, James has to dive deep into quite a few unpleasant philosophers, among them Herbert Marcuse, Jaques Derrida, Paolo Friere, and the postmodernists. And Hegel.

I had heard James describe before how Hegel saw the world. Hegel had this idea that progress is reached by opposite things colliding and out of them comes a new synthesis, and then that synthesis has to collide with its opposite and so on until perfection is reached. This process is called the dialectic. Marx took these ideas and applied them to society, where there has to be conflict and revolution, but then the new society that emerges isn’t perfect yet and so there has to be another revolution and so on until everything is perfect and/or everyone is dead.

Obviously I am simplifying a lot. James can talk about this stuff for an hour and he is simplifying too, not because these ideas are themselves complicated but because Hegel produced a huge dump of words, and he came up with terminology that tried to combine his ideas with Christian concepts so that they would be accepted in his era. Anyway, the word dialectic is still used by postmodern writers like Kimberle Crenshaw, and it is a clue that they think constant revolution is the way to bring about utopia.

So, I was familiar with Hegel through the podcasts of Lindsay, and I was also familiar enough with Gnostic thought to at least recognize it when it goes by, as it so often does. For one thing, you kind of have to learn a little bit about Gnosticism if you are a serious Christian, because gnostic (or at least pre-gnostic: Platonic, mystery religion) ideas were very much in the air in New Testament times, and many of the letters of the New Testament were written to refute these ideas. Also, Gnosticism, particularly the mind/body duality, has had such an influence on our culture that it’s hard to miss. It’s present in New Age and neopagan thought, and it’s called out in Nancy Pearcey’s book Love Thy Body for the bad effects it has had on the way we conceive of personhood.

So that’s the background.

Several months ago, I was listening to Lindsay give a talk summarizing his recent research to a church group. He was talking about theologies: systems of thought that make metaphysical and cosmological claims, and come with moral imperatives. And he dashed off this summary, something like the following:

“You could have a theology where at first all that exists is God, but He doesn’t know Himself as God, so in order to know Himself he creates all these other beings, and they are all like pieces of God but they don’t know it, and their task is to become enlightened and realize that they, too, are God, and when they realize this, eventually they will all come back together, but now God is self-conscious because of the process of breaking He’s been through.”

And I’m thinking, Sounds like Pantheism, or maybe Gnosticism.

And James says, “That’s the Hermetic theology.”

And I’ve got a new word to research.

So, why is it called Hermeticism? Does it have to do with hermits?

My first foray into Internet Hermeticism immediately showed that the school of thought was named for a guy named Hermes, as in this paragraph from wiki:

Hermeticism, or Hermetism, is a label used to designate a philosophical system that is primarily based on the purported teachings of Hermes Trismegistus (a legendary Hellenistic combination of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth).[1] These teachings are contained in the various writings attributed to Hermes (the Hermetica), which were produced over a period spanning many centuries (c. 300 BCE – 1200 CE), and may be very different in content and scope.[2]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hermeticism

One of my search hits, I can’t remember which one, said that Hermeticism is “often confused with Gnosticism.” O.K., so if it’s not Gnosticism, that means I know less than I thought and it’s all the more reason to research.

I also found avowedly Hermetic web sites like Hermetic World, whose “summary” is actually more of an attempt to draw you into their movement:

Hermeticism – The secret knowledge

Hermeticism is an ancient secret doctrine that dates back to early Egypt and its innermost knowledge has always been passed on only orally. In each generation there have been some faithful souls in different countries of the world who received the light, carefully cultivated it and did not allow it to be extinguished. Thanks to these strong hearts, these fearless spirits, truth has not been lost. It was always passed on from master to disciple, from adept to neophyte from mouth to ear. The terms “hermetically sealed”, “hermetically locked”, and so on, derive from this tradition and indicate that the general public does not have access to these teachings.

Hermeticism is a key that gives people the possibility to achieve everything they desire deep in their hearts, to develop a profound understanding of life, to become capable of decision making and responsibility; and to answer the question of meaning. Hermeticism offers a hidden key to unfolding.

Nobody can teach this knowledge to himself. Even in competent books like Kybalion, the teaching is only passed on in a veiled way. It always requires a master to pass on the wisdom to the able student. Today, as in the past, authentic mystery schools are a way to acquire this knowledge. The Hermetic Academy is one of these authentic schools.

https://www.hermetic-academy.com/hermeticism/

This is certainly the genuine article, but it is perhaps not the first place to go. I wanted to learn about the basic doctrines from a neutral source, simply and clearly described. I didn’t want to have to wade through a bunch of hand-waving to get there, at least not at first. Still, I suppose we shouldn’t be surprised that Hermetic World tries to cast a mysterious, esoteric, yet somewhat self-help-y atmosphere on their first page. After all, it is a mystery religion.

Well, at least now I know why it’s called Hermeticism. It’s basically an accident of history, due to the name of the guy to whom the founding writings were attributed.

Time to move on to a book.

I am fortunate to be descended from a scholar who has a large personal library, heavy on the theology.

I asked my dad.

Serendipitiously, he had just finished reading Michael J. McClymond’s two-volume history of Christian universalism (the doctrine that everyone is going to heaven), and he remembered that Hermeticism entered into the discussion. He was happy to lend it to me. You can see all the places I’ve marked with tabs. Those are just the ones where Hermeticism is directly mentioned. I hope you now understand my dilemma.

In McClymond’s Appendix A: Gnosis and Western Esotericism: Definitions and Lineages, I found at last the succinct, neutral summary I was looking for:

[“Hermetism”] as used by academics refers to persons, texts, ideas, and practices that are directly linked to the Corpus Hermeticum, a relatively small body of texts that appeared most likely in Egypt during the second or third centuries CE. … “Hermeticism” is often used in a wider way to refer to the general style of thinking that one finds in the Corpus Hermeticum and other works of ancient gnosis, alchemy, Kabbalah, and so forth. “Hermeticism” sometimes functions as a synonym for “esotericism.” The adjective “Hermetic” is ambiguous, since it can refer either to “Hermetism” or “Hermeticism.”

McClymond, p. 1072

O.K.

So it isn’t that different from Gnosticism after all.

“Esoteric,” by the way, means an emphasis on hidden or mystical knowledge that is not available to everyone and/or cannot be reduced to words and propositions. “Exoteric” refers to the style of theology that puts emphasis on knowledge that is public in the sense that it is written down somewhere, asserts something concrete, can be debated, etc.

Even though I have literally just found an actual definition of the word that is clear enough to put into a blog post, in the time it took me to find this definition I feel that I have already gotten a pretty good sense of what this philosophy is like. Perhaps it helps that it has pervaded many, many aspects of our culture, so I have encountered it many times before, as no doubt have you.

I began to peruse the tabs in the volumes above and read the sections there, in all their awful glory.

Yep, James Lindsay in fact did a pretty good job of explaining the core metaphysic of Hermeticism. Of course, this philosophy brings a lot of things with it that he didn’t get into. If we and all beings in the universe are all made of the same spiritual stuff as God Himself, it follows that alchemy should work (getting spiritual results with physical processes and the other way round). It follows that astrology should work (everything is connected, and the stars and men and the gods not only all influence each other, but when you get down to it are actually the same thing). It follows that reincarnation should be a thing (the body is just a shell or an illusion that is occupied by the spirit, the spark of God). It follows that there are many paths to God, since we are all manifestations of God and will all eventually return to Him/It. It follows that the body is not that important (in some versions of this philosophy, matter is actually evil). Therefore we should be able to physically heal ourselves with our minds. Our personhood should be unconnected to (some might say unfettered by) our body, such that we can be born in the wrong body, or we can change our sex or our species if we want to. There might also be bodies that don’t have souls yet (such as unborn babies), and so it would be no wrong to destroy them. Also, since matter is not really a real thing, it follows that Jesus was not really incarnated in a real human body and that He only appeared to do things like sleep, eat, suffer, and die. Also, since we are all parts of God like He is, He is not really one with God in any sense that is unique, but just more of an example of a really enlightened person who realized just how one with God He was.

I imagine that about twenty pop culture bells have gone off in your mind as you read that preceding paragraph. You might also have been reminded of the Church of Jesus Christ of the Latter-Day Saints, which teaches that we were all pre-existent souls literally fathered by God out of some sort of spiritual matter before we came to earth to be born.

Hermeticism is not just one thing. It’s a whole human tradition of thought. It had a lot of streams flowing into it, like Plato, first-century mystery religions, Gnosticism, and early attempts to reconcile Christianity with these things. It has a lot of streams flowing out of it, like many Christian mystics of varying degrees of Christian-ness; Origen; Bohme; Hegel; medieval and Renaissance alchemy; the Romantic literary movement; Mormonism; New Age thinking; identity politics; transhumanism; Shirley McLaine; The Secret, and the movie Phenomenon.

Not all of these thinkers hold to the exact same set of doctrines. In a big philosophical movement like this, almost every serious thinker is going to have his or her own specific formulation that differs from everyone else’s in ways that seem really important to people on the inside of the system. So anyone who is an insider or who has made it their life’s work to research any of the things I mention above (and many others besides) could come along and point out errors or overgeneralizations in this article and make me look like I don’t know anything. That’s partly because it’s a huge historical phenomenon and I actually don’t know much of all there is to know. It’s also partly because these mystery religions delight in making things complicated. They love to add rituals and symbols and secret names and to discover new additional deities that are personifications of abstract ideas like Wisdom. It’s supposed to be esoteric. That’s part of the fun.

Another reason it’s difficult to describe Hermeticism accurately is that when all is one, it is really difficult to talk about anything. In this view of the world, when you get right down to it there is no distinction between spirit and matter, creator and creature, man and woman, conscious and inanimate, and the list goes on. I called it Hermeticism at the beginning of this paragraph, but I was tempted to write Hermeticism/Gnosticism, or perhaps Hermeticism/Gnosticism/alchemy/mystery religions/the New Age/Pantheism/postmodernism. If you’ve ever read any New Age writers, you’ll notice that they tend to write important terms with slashes like that (“Sophia/the divine feminine”). That’s because it’s all one. They don’t want you to forget that. They don’t want to forget it. Even if these ideas do not go very well with the human mind, and they tend to break it if you keep trying to think them.

In a sense, Hermeticism and all these other related movements are very diverse and not the same at all. In another sense, it’s all … the same … crap.

Writing is a human practice.

Of course it is possible to have a human society without writing, but the impulse to devise a writing system, looked at historically, may have been the rule rather than the exception.

This is counter-intuitive, of course. “Symbolic logic” seems like it ought to be unnatural to humans, especially if we are thinking of humans as basically advanced animals, rather than as embodied spirits. But if we think of mind as primary, everything changes. It’s telling that reading and writing are one of the learning channels that can come naturally to people, in addition to the visual, the audio, and the kinesthetic. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

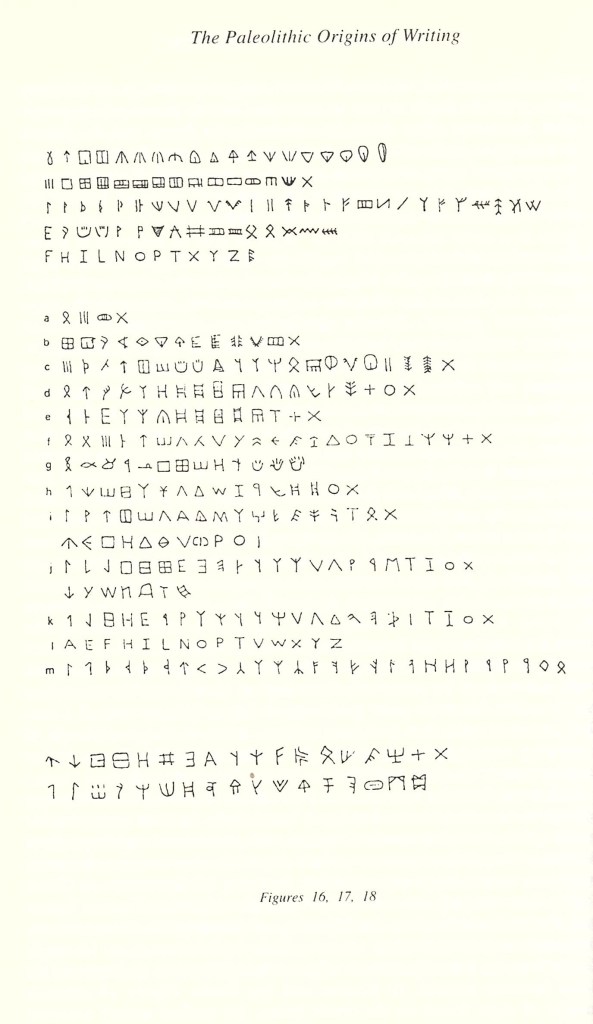

Welcome to the third post taken from Lost Civilizations of the Stone Age by Richard Rudgley. Call this the writing edition. This post hits the highlights of Rudgley’s chapters 4 and 5, pages 58 through 85.

The idea of writing as an exception in human history has become dogma:

The proposition that Ice Age reindeer hunters invented writing fifteen thousand years ago or more is utterly inadmissible and unthinkable. All the data that archaeologists have amassed during the last one hundred years reinforce the assumption that Sumerians and Egyptians invented true writing during the second half of the fourth millennium. The Palaeolithic-Mesolithic-Neolithic progression to civilisation is almost as fundamental an article of contemporary scientific faith as heliocentrism. Writing is the diagnostic trait … of civilisation. Writing, says I.J. Gelb, ‘distinguishes civilised man from barbarian.’ If the Ice-Age inhabitants of France and Spain invented writing thousands of years before civilisation arose in the Near East, then our most cherished beliefs about the nature of society and the course of human development would be demolished.

Allan Forbes and Thomas Crowder, quoted in Rudgley, p. 75

Of course, the demolishing of our most cherished beliefs about the course of human development is exactly what, Rudgley is arguing, is going to have to happen.

In the last few chapters I have selected only a small number of the complex sign systems that have been preserved from prehistoric times. My concentration on the Near East and more particularly on Europe should not be taken to imply that such systems did not exist elsewhere in the prehistoric world. Far from it; investigations of numerous collections of signs are being undertaken in places as far afield as the Arabian peninsula, China and Australia. Millions of prehistoric signs across the continents have already been recorded, and more and more are being discovered all the time. … It no longer seems sufficient to retain a simplistic evolutionary sequence of events leading up to the Sumerian [writing] breakthrough some 5,000 years ago.

Rudgley, p. 81

Let’s look at these complex sign systems that Rudgley has mentioned.

I was an adult before I ever heard the phrase “Old Europe.” I was doing research for a planned book, and I was surprised to learn that in southeast Europe (between the Balkans and the Black Sea), as early as 4,000 or 5,000 BC, there were not only cities but a writing system (undeciphered) known as the Vinca signs. It turns out that these cities and this writing system were probably part of a culture that obtained over much of Europe before the coming of the Indo-Europeans, which is called Old Europe. This is the culture that Marija Gimbutas believes was “the civilization of the goddess.”

Just as a reminder, these dates for the Vinca culture are before the very first human cities and writing are supposed to have arisen, in Sumeria in Mesopotamia, about 3,000 BC.

Perhaps I didn’t hear about the Vinca signs in school because they were only discovered in Transylvania 1961. (I was born in 1976, but we all know how long it takes new archaeological findings to get interpreted, integrated into the overall system, and eventually make it into school textbooks.) After being discovered, the signs were assumed to be derived from Mesopotamian cultures such as Sumer and Crete, because it was accepted dogma that writing was first invented in Mesopotamia. Later, the tablets on which the Vinca signs were discovered were carbon-dated and found to be older than the Mesopotamian writing systems. This led to a big disagreement between those who wanted to believe the carbon dates, and those who wanted to believe the more recent dates for Old European archaeological sites, which were then conventional.

Then, in 1969, more, similar signs were discovered on a plaque in Bulgaria and dated to be 6,000 – 7,000 years old. By this time, archaeologists were beginning to accept the carbon dating of these Old European sites. But since they still did not want to admit that writing might have been invented before Sumer, most of them decided “[the signs] could not be real writing and their apparent resemblance was simply coincidental.” (Rudgley p. 63)

An archaeologist named Winn analyzed the Vinca signs and while he is not willing to go further than calling them “pre-writing,” he concludes that they are “conventionalised and standardised, and that they represent a corpus of signs known and used over a wide area for several centuries.” (Rudgley 66)

Meanwhile, Marija Gimbutas and also Harald Haarmann of the University of Helsinki both feel the Vinca signs are true writing and that they developed out of religious or magical signs, not out of economic tallies like the Sumerian alphabet.

Haarmann notes that there a number of striking parallels between the various strands of the pre-Indo-European cultural fabric – especially those related to religious symbolism and mythology. Among these common features is the use of the bull and the snake as important religious symbols. In the case of the snake it is a form of the goddess intimately intertwined with the bird goddess motif in both Old European and later Cretan iconography. The bee and the butterfly are also recurrent divine attributes, and the butterfly is represented by … the double ax. Haarmann sees the goddess mythology of Old Europe echoed in these motifs that also feature prominently in the ancient civilisation of Crete. He then traces the links between the Old European script – as found in the Vinca culture – and later systems of writing, particularly those of Crete.

Rudgley, pp. 68 – 69

There are quite a number of symbols that appear on artifacts or are associated with paintings from the Neolithic and even the Palaeolithic period. These include crosses, spirals, dots, “lozenges” (ovals), and the zigzag, which is very common and seems to have been used to represent water. (By the way, note the zigzags among the Kachina Bridge petroglyphs.) “The discovery in the early 1970s of a bone fragment from the Mousterian site of Bacho Kiro in Bulgaria suggests that the use of the signs may date back to the time of the Neanderthals. This fragment of bone was engraved with the zigzag motif …” and apparently on purpose, not accidentally in the course of doing some other repetitive task. (Rudgley 73)

“The single V and the chevron (an inverted V) are among the most common of the recurrent motifs in the Stone Age.” (Rudgley p. 74) Gimbutas, of course, interprets the V as a symbol for the female genitals and/or Bird Goddess, but it could be just … you know … a symbol.

Archaeologist André Leroi-Gourhan has interpreted the many signs found at various Palaeolithic cave art sites not as a form of hunting magic (contra previous interpretations), but as a symbolic system. “Leroi-Gourhan admitted to us shortly before his death, ‘At Lascaux I really believed they had come very close to an alphabet.’” (Rudgley p. 77)

Every time some symbols are discovered that are so ancient they strain belief, anyone who doesn’t want to accept them as writing can easily go in to a number of calisthenic moves to cast doubt on this. If the item the signs are found on is in poor condition, they can question whether the marks were even intentional. Perhaps they were accidental scratches, the product of some other activity. If the marks are undeniably made by people, they can be dismissed as doodles. The Vinca signs, when first found, were speculated to have been copied randomly from Mediterranean signs by people who believed these things had mysterious power, but did not understand their meaning. Rudgley also notes that the Old European signs have been interpreted as purely magic symbols, as if a magical intent were to make them non-writing.

In short, any time we are presented with a complex system, there are always a million ways to get out of attributing it to a mind. This is doubly true if we aren’t able to interpret its meaning, but you will even see people do this with messages that they ought to be able to understand. Of course, it can also work the other way, where people see meaning in complex patterns where it wasn’t intended. Often what it comes down to is whether we want there to be a meaning there. Do we, or do we not, want to be in contact with another mind? If for whatever reason we don’t, we can always find a logical way to avoid that contact.

So in the case of apparent writing systems that we haven’t cracked and probably never will, our attitude towards them is going to depend heavily on what we believe about ancient people’s minds. Were they basically like ours, or were they different, animal? We will see more writing systems if we are expecting that they came from people. If we are not expecting to encounter people, then nothing is going to convince us that these are writing systems.

My mind was blown, while taking an Old Testament Backgrounds course years ago, when I read an essay that asserted that Adam was able to write and in fact had left a written record for his descendants.

This idea seems completely loony on the face of it … until you realize that the only reason it seems loony is that we are assuming that writing is a recent, unnatural development, the product of tens of millennia of human cultural evolution, and not a characteristic human activity that is, so to speak, wired in.

The essay interpreted the early chapters of Genesis in this way. There will be a short historical record, followed by the phrase “the book of [name],” indicating that the passage immediately preceding was by that author.

| Passage | Recounts | Closes with |

| Genesis 1:1 – 4:26 | Creation (in poetry), fall, Cain and Abel, some of Cain’s descendants, Seth | Gen. 5:1 “the book of Adam” |

| Gen. 5:1b – 6:8 | Recap of creation of Adam, Seth’s descendants up to Noah and his sons, Nephilim, God’s resolve to wipe out mankind, God’s favor on Noah | Gen. 6:9a “the book of Noah” |

| Gen. 6:9b – 11:9 | Building of the ark, the Flood, emerging from the ark, the Table of Nations, the Tower of Babel | Gen. 11:10 “the book of Shem” |

| Gen. 11: 10b – 11:26 | Genealogy from Shem to Terah and his son Abram | Gen. 11:27 “the book of Terah” |

| Gen. 11:27b – 25:18 | Terah moves his family to Haran, Terah dies, a whole bunch of stuff happens to Abram, death of Sarah, Isaac finds a wife, Abraham dies, genealogy of the Ishmaelites | Gen. 25:19 “the book of Abraham’s son Isaac” |

| Gen. 25:19b – 37:1 | Jacob’s entire life, death of Isaac, genealogy of Esau | Gen. 37:2 “the book of Jacob” |

I realize this might be a lot to accept. It’s just food for thought. It does explain why it says “the book of _________” (or, in my NIV, “this is the account of __________”), after the bulk of that person’s story.

(By the way … for those wondering about the title of this post … prostitution is referred to as “the world’s oldest profession.” Erma Bombeck, mother and humorist, has published a book hilariously titled Motherhood: The Second Oldest Profession. The title of this post references those two, because the post is about the fact that writing is very, very old. I don’t mean to imply that a writer’s life has any necessary connection to the other two professions, although of course this does invite all kinds of clever remarks.)

Once upon a time, in the 1950s, dating just meant “going on a date.” It was a very short-term commitment, lasting only a few hours. You went out for ice cream or whatever, and then you went home. If you couldn’t stand the person, there was a natural limit to how long to you had to spend with them (the length of the date). If you liked each other, you might go on another date some time. But you were not bound to go on date after date with the same person. The idea was to go out with a variety of people, to get a sense of what sort of person might be for you. Eventually, you might “go steady” with a person you really liked, and maybe eventually get married.

But then … the Sexual Revolution happened. The expectation that a date might mean actually having sex was introduced. Suddenly, dating a variety of people made less sense. It clashed with the old-fashioned sexual mores (and with common sense) that said it wasn’t good to sleep around. Now, “going steady” with one person became the norm, and people who dated around were seen in a negative light. After all, if you were going to be sexually involved with somebody, it had better be with just one person at a time.

Futhermore, because this was a big societal shift, now nobody knew what the rules were. On the part of some of the drivers of the sexual revolution, this was intentional. They thought that society, rules, and norms as such were inherently oppressive, and that getting rid of all these things would usher in a hippie, free-love paradise. What it actually ushered in was total confusion. And while total confusion might work to the advantage of a few libertines who want to live completely unrestricted, it stresses out regular people (especially young people) who just want to know what they are supposed to do.

This confusion has persisted from my generation (X) down to the present day. It creates endless amounts of frustration, misunderstanding, and wheel-spinning as generation after generation struggles to re-invent the wheel. It also creates lots of tension and hostility between the sexes, because as it turns out, the way men naturally approach things and the way women do, do not mesh terribly well when completely unguided by any kind of norm.

Christians, naturally, had their own reactions to all of this. We looked at modern dating, which could mean getting very sexually involved as a teen, cohabiting as a young adult, and so on, clapped our palms to our cheeks, and went “AAAAAG! This is not right!” Nor were we wrong. When I was growing up, in the 90s, the choice seemed to be between trying to do the highly risky methods of modern dating – but hopefully in such a way that you didn’t have sex before marriage, although that was kind of a crapshoot to be honest – or taking the sensible course and not dating at all. I, and many other Christians, went for the latter, but this left us without any path to get to know the opposite sex or find a suitable spouse.

Some Christian communities decided that the solution to all this confusion was “courtship” — or, as some called it, “biblical courtship.” One of the early advocates of this system was Douglas Wilson, a pastor and writer for whom I still have great deal of respect. Courtship seemed to a lot of people, myself included, like a godly alternative to the train wreck we were witnessing. Unfortunately, in an effort to avoid the train, the courtship car drove directly into the other ditch, into a wreck that was equally fiery. That’s what Thomas Umstattd Jr.’s book is about.

As older Gen Xers, my now-husband and I dodged a bullet on this one. We had both read some Douglas Wilson and we both saw the problems with modern dating since the 60s, and so when we met and realized we kinda liked each other, we wanted to do some kind of courtship. However, both of us were adults, out of the house, and living hundreds of miles away from our parents. I had gone to university, then lived with my parents again for a year while working so I could go to missions school. My husband, almost a decade older, had been to university, grad school, and had lived in various countries overseas. So, we were fully launched. Still, we tried to “court.” My husband e-mailed my dad (yes, e-mailed) and asked for permission to date me. I called my dad and said, “Aren’t you going to ask me what I think?” and he said, “Well, I assume you like him?”

In our case, “courtship” ended up meaning little more than meeting each other’s parents, getting to know them, and showing them honor as we prepared for marriage. And that’s certainly not a bad thing. But it’s very different from how it was implemented in some Christian communities, where the parents were hard-core.

When I write about courtship online, defining courtship often becomes the most controversial point in the comments. I believe that the lack of clear definition may be contributing to the crisis.

Each community feels that its form of courtship is superior to the others. Many feel that any problem pointed out in Modern Courtship as a whole doesn’t apply to them.

Umstattd, p. 53

As such, Umstattd describes courtship with a list of common characteristics:

These bullet points are taken from pages 53 to 64 of the book.

Getting too serious too soon is a problem that Modern Dating and Modern Courtship share. Both of these systems result in singles going through one committed, heartbreaking relationship after another. They differ only in frequency and style of intensity. Modern Dating is more physically intense, while Modern Courtship of often more emotionally intense. Going steady too soon is one of the leading causes of unnecessary heartbreak for young people.

ibid, p. 88

In other words, the courtship crowd, in an effort to fix the inappropriate sexual involvement of modern dating, turned the dial in exactly the wrong direction: in the direction of more intensity, not less! This leads to more heartbreak, not less. That, if I had to sum it up, is the thesis of this book.

Umstattd goes into some detail about additional problems, one of which is the enormous amount of leverage that the courtship system gives to overprotective dads. The result is young men who are never allowed even to take a young woman out for coffee, and consequently feel like failures, and young women who feel unattractive, unaware that there are many young men who would like to date her, but her dad has been screening them out without even telling her.

The [Christian] Baby Boomers created the rules of courtship out of fear. They wanted to protect their children from the mistakes they made during the Sexual Revolution and its aftermath. The rules came from good intentions.

During the 1990s and early 2000s, millions of young people embraced the tenets of courtship in part or in whole. And it’s no wonder why — in a culture where we demonized dating, and divorce ran rampant, Modern Courtship seemed like the only alternative.

Many of those young people are still single today, but they don’t have to be.

If you’re one of the millions of frustrated singles, there’s hope for you: there’s an easier path to marriage that’s more fun and still honors God.

If we want to get back to the marriage rates of our grandparents, we need to learn from them and adopt their approach. It’s my hope that the Traditional Dating practiced by our grandparents will be part of the solution to resolving the Courtship Crisis.

Umstattd, p. 68

In other words, according to Umstattd, the way to date like a normal person is to date the way your grandmother (or maybe now, great-grandmother) would have: don’t go out with the same fellow twice, and be home by ten.

I really wish this had been the system when I was growing up. Courtship wasn’t really a thing in my circles, so we were left, as I said, with Sexual Revolution or Nothing. Or Make It Up As You Go. Consequently, although not scarred by purity culture or courtship, I was one of those women who felt unwanted and never got asked out … and was afraid to say yes on the rare occasions when I was.

I would like my kids to be able to enjoy the practice of Traditional Dating. However, there’s a problem. Traditional Dating, like any society- or community-wide custom, depends upon everybody knowing the rules. Everybody does not know the rules. In my observation, most Zoomers still have the expectation that once a boy and girl go out or hang out once, they are “a couple” until further notice (whether that means they are sexually involved or not), and would have to “break up” if they wanted to go out with someone else. I’d like to take this pressure off our kids. But, as with so many cultural rebuilding tasks, it looks as if we are going to have to do this the hard way. Which means doing it on a case-by-case basis, with parents of Christian young people talking to one another about norms and expectations.

I would really love it if the parents of all the young women my sons know would read this book.

A major goal of the courtship trend, as well as purity culture (“guard your heart!”) was to avoid heartbreak. And yes, there is a large amount of totally unnecessary heartbreak that the sexual revolution had brought to those who faithfully practices its tenets. (Idols always devour their worshippers.) I absolutely agree that it ought to be possible to live in this world without throwing your heart and body out into the arena, going out and collecting heartbreak after heartbreak, trauma after frustrating and degrading trauma.

However, that doesn’t mean that it’s possible to go from being a kid to being a married adult without ever getting your heart broke.

Being a teenager is rough in every society. You feel things more intensely. Finding a wife or husband is a challenge in every society. Most people are going to have some near misses.

In other words, no system, certainly not courtship but also not Traditional Dating, guarantees protection from living in a fallen world. And no system, however wise, guarantees every person a smooth, easy path to marriage.

When applying Scripture, particularly the Old Testament, we have to differentiate between biblical practice, principle, and command. Just because Jacob had two wives and a seven-year engagement doesn’t mean that God wants all men to have two wives and seven-year engagements.

What we have in the Old Testament are a lot of stories: each one different from the others.

Sometimes a woman is the protagonist in a romance (such as Ruth with Boaz) and at other times the man takes the lead (like Jacob with Rachel). There are arranged marriages (Isaac and Rebekah) and women who entered marriage through a harem (David and Abigail, Michal, and Bathsheba). Some women even chose their own husbands (Zelophehad’s daughters).

The Bible is surprisingly quiet when it comes to laying out a system of courtship. In fact, Jesus even qualified the Old Testament marriage laws when He said the divorce code was written because of the hardness of Israel’s hearts (Matt. 19:8).

The Apostle Paul, who is usually very direct, speaks with all kinds of qualifiers when talking about romantic relationships. He makes a special point to say that not all of his instructions are from the Lord in I Corinthians 7:25 – 28. I can’t think of another topic where Paul is this cautious with his words.

Could it be that God expects courtship systems to reflect the culture of the folks getting married?

What we need is a system to help young people make good decisions.

Umstattd, pp. 65 – 67

Gary Bates, interviewed by Jon Harris on Conversations That Matter, is the most sane and humane UFOlogist you could hope to meet.