We are a tropical species.

Dr. Patrick Moore

Tag: anthropology

Funny Social Commentary of the Week

Stephen Renney was in his windowless office, eating a sandwich and drinking Fanta from a can. He sensed me standing in his doorway, looked up and then started making those slightly embarrassed, fidgety movements we all make when we’ve been caught eating alone. As though eating were some sort of not-quite-respectable indulgence instead of the most natural thing in the world.

“Sorry,” I said, giving the time-honoured response, and looking slightly embarrassed myself, as though I’d caught him on the loo.

“Not at all,” he responded, ridiculously forgiving me.

Sacrifice, by S.J. Bolton, p. 299

Misanthropic Abandoning of the Communist Experiment of the Week

All this while no supply [from England] was heard of, neither knew they [the Pilgrims] when they might expect any. So they began to think how they might raise as much corn as they could, and obtain a better crop than they had done, that they might not still thus languish in misery. At length, after much debate of things, the Governor (with the advice of the chiefest among them), gave way that they should set corn every man for his own particular, and in that regard trust to themselves; in all other things to go on in the general way as before. And so assigned to every family a parcel of land, according to the proportion of their number, for that end, only for present use (but made no division for inheritance) and ranged all boys and youth under some family. This had very good success, for it made all hands very industrious, so as much more corn was planted than otherwise would have been by any means the Governor or any other could use, and saved him a great deal of trouble, and gave far better content. The women now went willingly into the field, and took their little ones with them to set corn; which before would allege weakness and inability; whom to have compelled would have been thought great tyranny and oppression.

This experience that was had in this common course and condition, tried sundry years and that amongst godly and sober men, may well evince the vanity of that conceit of Plato’s and other ancients applauded by some of later times; that the taking away of property and bringing in community into a commonwealth would make them happy and flourishing; as if they were wiser than God. For this community (so far as it was) was found to breed much confusion and discontent and retard much employment that would have been to their benefit and comfort. For the young men, that were most able and fit for labour and sevice, did repine that they should spend their time and strength to work for other men’s wives and children without any recompense. The strong, or man of parts, had no more in division of victuals and clothes than he that was weak and not able to do a quarter the other could; this was thought injustice. The aged and graver men to be ranked and equalized in labours and victuals and clothes, etc., with the meaner and younger sort, thought it some indignity and disrespect unto them. And for men’s wives to be commanded to do service for other men, as dressing their meat, washing their clothes, etc., they deeemed it a kind of slavery, neither could many husbands well brook it.

Upon the point all being to have alike, and all to do alike, they thought themselves in like condition, and one as good as another; and so, if it did not cut off those relations that God hath set amongst men, yet it did at least much diminish and take off the mutual respects that should be preserved amongst them. And would have been worse if they had been men of another condition [i.e., character]. Let none object this is men’s corruption, and nothing to the course [of communism] itself. I answer, seeing all men have this corruption in them, God in His wisdom saw another course fitter for them.

William Bradford, Of Plymouth Plantation 1620 – 1647, pp. 132 – 134

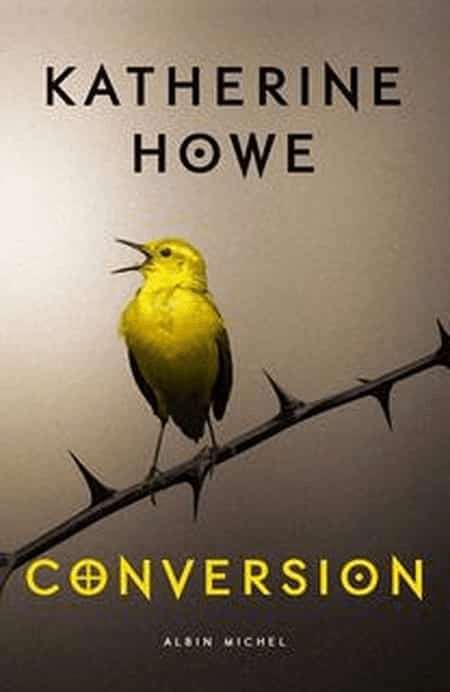

Conversion: A Book Review

My vision is crowded with whispers and movement and strange shapes narrowing in. I feel my heart thudding in my chest, the sweat flowing freely in my hair, under my arms.

Something inside me breaks. I close my eyes and open my mouth, and a piercing scream tears out of me. The scream relieves the pressure in my head, and it feels so good that I scream again.

“It’s there!” I jabber, lurching in my seat. “I see it there! Goody Corey’s yellow bird sits on Reverend Lawson’s hat! I see it plain as day, the Devil’s yellow bird sits on the Reverend’s hat!”

Conversion, p. 362 – 363

I picked up this book from the public library, among a few others, to have fiction to read over Christmas break. After one false start (a high-school drama that was unable to hold my attention), I cracked open Conversion, and it was a winner.

Here’s the blurb from Howe’s website:

A chilling mystery based on true events, from New York Times bestselling author Katherine Howe.

It’s senior year, and St. Joan’s Academy is a pressure cooker. Grades, college applications, boys’ texts: Through it all, Colleen Rowley and her friends keep it together. Until the school’s queen bee suddenly falls into uncontrollable tics in the middle of class.The mystery illness spreads to the school’s popular clique, then more students and symptoms follow: seizures, hair loss, violent coughing fits. St. Joan’s buzzes with rumor; rumor erupts into full-blown panic.

Everyone scrambles to find something, or someone, to blame. Pollution? Stress? Are the girls faking? Only Colleen—who’s been reading The Crucible for extra credit—comes to realize what nobody else has: Danvers was once Salem Village, where another group of girls suffered from a similarly bizarre epidemic three centuries ago . . .Inspired by true events—from seventeenth-century colonial life to the halls of a modern-day high school—Conversion casts a spell.

The story goes back and forth between modern St. Joan’s and 17th-century Salem. The excerpts from Salem are fairly long. I would say they take up a quarter to a third of the book. The Salem storyline is told from the perspective of Ann Putnam, one of the “afflicted” girls who, years later, made a public apology which stated that she now thought the people accused of witchcraft had been innocent.

Coming into this, I wasn’t sure I would finish it. Books about the Salem witch frenzy, after all, can easily go sideways into facile Christianity / patriarchy bashing. And at first, it did look like Howe was implying that: It’s suh-sigh-uh-tee! These girls had no pow-er! Some of them were servants! The first person they accused was a slave! However, Howe never veered into caricatures. She painted a fairly complex picture, held the girls also responsible, and the writing was good enough that I ended up finishing the book.

I do think Howe’s interpretation of what went down would be more feminist than my own. In the Salem scenes, the men are, to a person, cold, harsh, and uncaring as fathers. (Also, the women can’t read.) However, in the Danvers scenes, Colleen has loving, involved parents who are still married, a kindly younger brother, an apparently goodhearted boyfriend, and a priest at her school who seems like a good egg. The pressure on the Danvers girls comes more in the form of an academically competitive environment where they are all hoping to get into Ivy League colleges. In fact, the fact that none of the girls’ parents seem to be divorced is striking.

Spoiler Town

Howe’s diagnosis of the St. Joan’s girls – and, apparently, of the Salem girls also – is a medical phenomenon called conversion, whereby intense mental stress is “converted” into bizarre physical symptoms.

In the case of the Salem girls, as Howe tells it, it begins with one little girl who genuinely takes sick with what used to be called a nervous breakdown. It’s implied, but never drawn out, that she has been abused by her father. The phenomenon is then taken up by a servant girl living in the same house who is clearly faking at first, for attention and to get out of being worked hard. She even bites herself on the arm to manifest mysterious wounds. The phenomenon then spreads through a combination of this particular girl enjoying the attention; other girls being unwilling to speak up but just saying what they think the adults want to hear; possible suggestion as the girls work themselves into a genuine state; and simmering resentments in the town, as the girls and their parents use the trials to get revenge on those they envy.

In the case of the St. Joan’s girls, Howe is able to offer medical explanations for even the most bizarre physical phenomena. For example, one girl who has been coughing up pins turns out to have pica (a mineral deficiency that causes a compulsion to eat things that are not food, such as dirt). You see, there is a medical explanation for everything!

This book was published in 2014 and the modern-day story is set in 2012. Now, since the Plandemic, Howe’s trust of the medical establishment struck me as naive and dated. The Department of Public Health is the voice of sanity in the St. Joan’s hysteria, and it’s they who figure out that conversion (not the HPV vaccine or environmental pollution) is what’s causing it. Near the end of the book, when the phenomenon has been taken care of by these experts, Colleen narrates that “We are all on the same antidepressant.” This is a red flag to anyone who’s familiar with the research about how harmful behavioral meds can be to kids and teenagers, and how they have been chronically overprescribed, often for way too long at a time, and what a huge moneymaker they are for pharmaceutical companies. I have only a very basic, passing familiarity with this stuff, and even I was concerned. But Howe seems to believe in The Science just as firmly as the Puritains believed in The Devil.

Nevertheless, Howe draws back from explaining away the strange phenomena completely. There’s an odd scene near the end of the book when Colleen’s best friend’s mother, who is always described as pale blonde, ghostly, suffering from migraines, and almost never leaving her house, pulls Colleen into a dark corner and whispers creepily that her daughter is “like me.”

“She’s prone to spells. But it can be managed. Helps to have the family close by. I’m only telling you so you don’t have to worry.”

My mouth went dry.

“But how did you –” I stopped, because it almost seemed as though her eyes were glowing faintly red.

“Anyhow,” Mrs. Blackburn said, her smile widening, a tooth glinting in the darkness under the stairs, “They said what caused it, in the news. Didn’t they.”

“Y — yes.” I swallowed.

“Good. So there’s no problem.”

The hand released my wrist.

ibid, p. 393

I’m not sure what the purpose of this creepy scene is. Is Howe trying to buy back the “mystery” element of her book, even though by that point in the story, all the explanations have been offered? If she is trying to keep the story somewhat paranormal, I’d say the attempt is not successful. Nothing else that happens in the book, not even the scenes in Salem, hint that any actual paranormal activity might be going on. It is all just the girls’ minds deteriorating. Or is Howe trying to imply that Mrs. Blackburn is displaying Munchhausen by Proxy and is somehow making her own daughter sick? If that’s the theory, it’s way too late in the novel to introduce it, and it never gets further explored. There does seem to be a longer version of this book (“not condensed”) out there. Perhaps the Mystery of Mrs. Blackburn is explained in the longer version, but in the book I read, it just comes off like the author wants to add complexity even though she clearly believes the Harmless Medical/Societal Pressure Explanation.

When Witchcraft Was a Thing

I do not know enough about the Salem witch trials — or witch trials in general — or even the Puritains, although I have read some of them — to speak authoritatively about the degree to which Howe’s explanations are correct. Howe has done a lot of research about the Salem trials, and even includes long excerpts from the transcripts in her novel. It’s not clear, however, whether she has done much research about other witch trials in New England (or Old England), or about Puritan theological beliefs.

Fortunately, I have a book by someone who has.

When you read a lot, serendipities sometimes happen. I bought this book many, many years ago, at a used book shop in Kansas City, when I was there for a vacation with extended family. My dad has Used Bookstore Radar, and he always likes to visit the used bookstores whenever he is in a strange city. So I went with him and bought my own armload. This book was an impulse buy that survived several rounds of elimination, because Salem was one of those historical topics that I “really needed to learn more about.” Well, now the time has come.

John Putnam Demos, interestingly, found out only after he had begun witchcraft research that he is descended from the Putnams, the family who were instrumental in many of the witchcraft convictions in Salem.

I’ve only begun the book, but here is what I can tell you. Although Salem has become famous for cases getting out of hand, witchcraft (“entertaining Satan”) was a recognized crime during the 1600s, on both sides of the Atlantic. As with other crimes under English common law, any accusation had to be first investigated informally, and many of these were settled without going to court, which means we have no official records of them. If the stage of going to court was reached, there were still legal proceedings, evidence presented, and so forth, and the magistrates could and often did acquit the accused or void the case on a technicality. People who had been accused of witchcraft could also sue their accuser for slander. Some countries, and some regions of each country, prosecuted people for witchcraft far more often than others.

It is this background of which Demos wants to draw a detailed picture. He tells us that he is going to look at the biographical details of certain accused and accusers. He is going to look at this from a sociological, psychological, and historical point of view. I am sure I will learn a lot from him. But, when it comes right down it, Demos is still studying witch trials as a sociological phenomenon. He is not examining whether the paranormal may have played an actual role.

The Dominant Narrative

Possibly the most annoying scene in Conversion is when Colleen’s teacher, Ms. Slater, tells Colleen that a good historian should “look beyond the dominant narrative” about Salem. I’m not certain what Slater thinks the “dominant narrative” about the Salem witch trials is. Surely, in modern times, most people see nothing more than a story of injustice and superstition played out in an overly rigid, hierarchical society. That’s certainly not the narrative that was dominating in Salem at the time. The only way I can detect that Slater’s preferred emphasis differs from the dominant modern narrative, is that she wants us to have more sympathy for the teenaged girls who were doing the accusing, for the pressure they were probably under.

This is actually a new thought. If I may speak from my own experience, when we read accounts of the trials, the girls definitely come off as the villains of the piece: screaming accusations, making their adult victims cry. The tendency is to attribute malice. I wouldn’t say that comes from listening to a narrative told by people in power, though; rather, it’s the immediate first impression that we get from just observing their behavior.

By contrast, here’s how Ann Putnam’s experience went down in Conversion:

“Oh, Annie, tell them how we suffer!” Abigail beseeches me.

“I … I …” I stumble over my words, terrified. If I continue the lie, I’m sinning in the eyes of God. A vile, hell-sending sin. If I speak the truth, I’ll be beaten sure, and all the other girls will, too. My mouth goes dry, and bile rises in my throat.

At length, I whisper, “I cannot say whose shape it is.”

page 221

And here:

I’m beginning to panic, and I want to get up and run away [from the courthouse] and hide in the barn behind our house, but everyone is there and everyone is watching me, and my father is there and I have to stay strong and do what they want me to, and so I stay where I am, making myself small on the pew, and soon enough the tears are springing from my eyes, too.

page 258

The picture here is of a girl trapped in a story she knows there is something wrong with, but afraid to out her friends and to displease the adults. This is also very plausible. It reminds me of so-called “trans” children, trapped in an even more harmful delusion foisted upon them by the adults in their lives and by their peers, manipulated into believing this is what they themselves want and have chosen. This could have been one of many factors operating in Salem. This is how social contagions work. There is a big lie; there are vulnerable, confused children or teenagers; there are culpable adults and confused adults; there is social pressure; there is mass deception.

Multiple Causes

So let’s look at some factors, remembering that many things can be true at once.

- Hysterical Teenaged Girls: Teen and pre-teen girls tend to be stressed out in every society. Their bodies are changing, they are noticing boys, hormones are making them nervous and emotional and edgy. No, they don’t have much social power, but we need to consider whether it is actually a good idea to give teen girls a lot of social power. I think most girls hate themselves at thirteen (the age of Ann Putnam when the story takes place). Teen girls are also known to be susceptible to fads, suggestion, and yes, physical symptoms of stress. The fact that they are not very mentally stable is not an indictment of them or even necessarily of their society; it’s more of a fact that we all have to deal with. This is also the age when, unless guided, girls develop an interest in the occult. So yes, it does seem very natural that the accusers at Salem should have been a bunch of teen girls, and it’s very believable that they were not just “faking,” but had worked themselves into an actual altered state. This created a perfect storm at Salem, because the evidence to be examined a witch trial generally consisted of eyewitness testimony. These were not very reliable witnesses. But the fact that teen girls’ testimony was accepted as evidence actually argues against Salem being a sexist hellhole.

- Vengeance / Scapegoating: Already in Demos’ book, it has become evident that people who got accused of witchcraft tended to be those who had annoyed their neighbors in some way. Maybe they were the sort of person who is always arguing with everyone, or maybe they were upper-class or especially pious and so the target of envy. It’s pretty clear, even to someone not deeply familiar with the records, that accusers saw in a witch trial a way to get revenge on someone who they had perceived wronged them. Envy, resentment, and scapegoating are actually very common in human life, especially in village settings (say as opposed to city settings). If the culture in question believes in magic, then people are likely to suspect their enemies of sabotage by magic, in whatever magical idiom is local to the culture. People find it hard to accept that things can just go wrong for them. They prefer to blame someone when something goes wrong.

- Superstition: If by “Superstition” we mean “There’s no such thing as witchcraft,” then we will get to that in a moment. But if by superstition we mean, “If the New Englanders had not believed in witchcraft, the injustice of the Salem witch trials would never have happened,” then that is manifestly untrue. Of course, they would not have happened in the same way. But what scares us about Salem is not the suggestion of the paranormal so much as the purge-like quality of the proceedings, where an accusation is tantamount to a conviction, and it’s impossible for the accused to prove their innocence. Something has gone wrong with way rules of evidence are applied. A moment’s reflection will show that it is completely possible to conduct a purge in the absence of belief in witchcraft. Purges have been conducted on charges of capitalism, communism, being a heretic, being a Christian, sympathizing with the enemy in wartime, abusing children in daycare centers, date rape on college campuses, racism, not taking the government vaccine, and being insufficiently supportive of the trans agenda. If the purge mentality is present, then any superstition will do. That’s why it is foolish for us to feel superior to the Salem townspeople, as if, not being Puritans, we could never be subject to this common human practice.

- Medical Causes: I have heard theories that there may have been some physical factor, such as a particular kind of mold in their diet, that caused the girls to develop delusions and hallucinations. This seems to me like a modern materialist grasping at straws. We don’t want to believe that a bunch of teenaged girls could be so wicked as to deliberately send their neighbors to their deaths, and we certainly don’t want to consider the paranormal as a real possibility, so it must be the mold. It’s true that certain medical conditions can cause irrational behavior (even heat stroke or fever can do it), because we are embodied people. However, in a case like that I wouldn’t expect the affliction to spread like a fad among just the teen girls in a community … the very ones who are vulnerable to delusions and drama for a bunch of other reasons already covered.

- Actual Occult Activity: Not being a strict materialist, I can’t rule this possibility out. Modern Western materialists don’t believe that a spiritual world exists at all, so when it comes to interpreting things that happened in the past, we have some blind spots. We are quick to accuse people who we know to be otherwise intelligent of making ridiculous things up out of whole cloth, or of believing ridiculous things completely without evidence. But it is actually possible that there was a lot more paranormal activity in the past than now. Paranormal activity tends to manifest itself in forms that make sense to the culture where it is manifesting; so, people in Ireland have encounters with fairies, American Indians might encounter the Windigo, and modern Americans are more likely to be abducted by aliens. This doesn’t mean that nothing spiritual is going on, just that malevolent spiritual forces know how to make themselves intelligible to humans. If we accept that there was actual paranormal (dare I say, demonic) activity happening in Salem, this does not mean that we have to accept that every person who was accused – or even every person who confessed – was in fact a witch in league with the devil. There have been cases before where people confessed to things they didn’t do, because they were worn down by interrogation, eager to please, or easily manipulated. However, there could have been some people practicing the occult in Salem. The girls themselves could have gotten involved in some occult practice, which could have left them open to demonization. And in fact, even if their symptoms were entirely faked, the kind of mob/purge mentality that they displayed is always the work of the devil in the sense of being the fruit of envy, deception, and a false ideology. When people get involved in occult practice or philosophy, one tragic result is often that they lose their ability to think clearly. That certainly seems to have happened in Salem, in some form or other. The devil certainly got a lot of publicity during those months, and I’m sure he was loving it.

Altai Throat Singing

The Altai mountains are in central Asia, north of the Himalayas, around the area where countries such as China, Mongolia, Russia, and Kazakstan meet. They are not too far from the stompin’ grounds of the horse-riding Central Asian tribes such as the Scythians and Parthians, part of the same culture area that gave rise to the early Indo-Europeans with their kurgans, before they moved west into Europe proper. That’s why these guys look sort of European and sort of Asian. People who live here have looked like this for thousands of years.

The Altai mountains are an old range of mountains (left over from Pangea?), not created by whatever event caused the Himalayas. Hence, they are low and rolling. I had to (lightly) research this part of the world when I went to write The Long Guest. My characters called them the Gentle Mountains. They had a lodge there for some years before moving on to the Gobi desert (which possibly didn’t actually exist in the immediate post-flood years in which my story is set, but we will ignore that. Onward!)

I thought this was a perfect video to share on a winter’s day. Are these people cool or what? I love how he warms up for throat singing by making horse noises.

As with many cultures, my imagination is very attracted to their way of life, but I would probably hate it if I had to actually live that way, not being tough enough.

Thank You, St. Boniface: A Repost About Christmas

This post is about how we got our Christmas trees. For the record, I would probably still have a Christmas tree in the house even if it they were pagan in origin. (I’ll explain why in a different post, drawing on G.K. Chesterton.) But Christmas trees aren’t pagan. At least, not entirely.

My Barbarian Ancestors

Yes, I had barbarian ancestors, in Ireland, England, Friesland, and probably among the other Germanic tribes as well. Some of them were headhunters, if you go back far enough. (For example, pre-Roman Celts were.) All of us had barbarian ancestors, right? And we love them.

St. Boniface was a missionary during the 700s to pagan Germanic tribes such as the Hessians. At that time, oak trees were an important part of pagan worship all across Europe. You can trace this among the Greeks, for example, and, on the other side of the continent, among the Druids. These trees were felt to be mystical, were sacred to the more important local gods, whichever those were, and were the site of animal and in some cases human sacrifice.

God versus the false gods

St. Boniface famously cut down a huge oak tree on Mt. Gudenberg, which the Hessians held as sacred to Thor.

Now, I would like to note that marching in and destroying a culture’s most sacred symbol is not commonly accepted as good missionary practice. It is not generally the way to win hearts and minds, you might say.

The more preferred method is the one Paul took in the Areopagus, where he noticed that the Athenians had an altar “to an unknown god,” and began to talk to them about this unknown god as someone he could make known, even quoting their own poets to them (Acts 17:16 – 34). In other words, he understood the culture, knew how to speak to people in their own terms, and in these terms was able to explain the Gospel. In fact, a city clerk was able to testify, “These men have neither robbed temples nor blasphemed our goddess” (Acts 19:37). Later (for example, in Ephesus) we see pagan Greeks voluntarily burning their own spellbooks and magic charms when they convert to Christ (Acts 19:17 – 20). This is, in general, a much better way. (Although note that later in the chapter, it causes pushback from those who were losing money in the charm-and-idol trade.)

However, occasionally it is appropriate for a representative of the living God to challenge a local god directly. This is called a power encounter. Elijah, a prophet of ancient Israel, staged a power encounter when he challenged 450 priests of the pagan god Baal to get Baal to bring down fire on an animal sacrifice that had been prepared for him. When no fire came after they had chanted, prayed, and cut themselves all day, Elijah prayed to the God of Israel, who immediately sent fire that burned up not only the sacrifice that had been prepared for Him, but also the stones of the altar (I Kings chapter 18). So, there are times when a power encounter is called for.

A wise missionary who had traveled and talked to Christians all over the world once told me, during a class on the subject, that power encounters tend to be successful in the sense of winning people’s hearts only when they arise naturally. If an outsider comes in and tries to force a power encounter, “It usually just damages relationships.” But people are ready when, say, there had been disagreement in the village or nation about which god to follow, and someone in authority says, “O.K. We are going to settle this once and for all.”

That appears to be the kind of power encounter that Elijah had. Israel was ostensibly supposed to be serving their God, but the king, Ahab, had married a pagan princess and was serving her gods as well. In fact, Ahab had been waffling for years. There had been a drought (which Ahab knew that Elijah — read God — was causing). Everyone was sick of the starvation and the uncertainty. Before calling down the fire, Elijah prays, “Answer me, O LORD, answer me, so these people will know that you, O LORD, are God, and that you are turning their hearts back again.” (I Kings 18:37)

Similar circumstances appear to have been behind Boniface’s decision to cut down the great oak tree. In one of the sources I cite below, Boniface is surrounded by a crowd of bearded, long-haired Hessian chiefs and warriors, who are watching him cut down the oak and waiting for Thor to strike him down. When he is able successfully to cut down the oak, they are shaken. “If our gods are powerless to protect their own holy places, then they are nothing” (Hannula p. 62). Clearly, Boniface had been among them for some time, and the Hessians were already beginning to have doubts and questions, before the oak was felled.

Also note that, just as with Elijah, Boniface was not a colonizer coming in with superior technological power to bulldoze the Hessians’ culture. They could have killed him, just as Ahab could have had Elijah killed. A colonizer coming in with gunboats to destroy a sacred site is not a good look, and it’s not really a power encounter either, because what is being brought to bear in such a case is man’s power and not God’s.

And, Voila! a Christmas Tree

In some versions of this story, Boniface “gives” the Hessians a fir tree to replace the oak he cut down. (In some versions, it miraculously sprouts from the spot.) Instead of celebrating Winter Solstice at the oak tree, they would now celebrate Christ-mass (during Winter Solstice, because everyone needs a holiday around that time) at the fir tree. So, yes, it’s a Christian symbol.

Now, every holiday tradition, laden with symbols and accretions, draws from all kinds of streams. So let me hasten to say that St. Boniface was not the only contributor to the Christmas tree. People have been using trees as objects of decoration, celebration, and well-placed or mis-placed worship, all through history. Some of our Christmas traditions, such as decorating our houses with evergreen and holly boughs, giving gifts, and even pointed red caps, come from the Roman festival of Saturnalia. This is what holidays are like. This is what symbols are like. This is what it is like to be human.

Still, I’d like to say thanks to St. Boniface for getting some of my ancestors started on the tradition of the Christmas tree.

Bonus rant, adapted from a discussion I had …

... in a YouTube comments section with a Hebraic-roots Christian who was insisting that Christmas is a “pagan” holiday:

So, as we can see, the evergreen tree is a Christian symbol, not a pagan one, and has been from the very beginning of its usage. St. Boniface cut down the tree that was sacred to Thor, and that was an oak tree, not a Christmas tree. Sacred oaks are pagan. Christmas trees, which incidentally are not actually considered sacred, are Christian.

Yes, I am aware, as are most Christians, that Jesus was probably not actually born on Dec. 25th. Yes, I am aware that Yule was originally a pagan feast time.

But let’s look at the symbolism, shall we?

For those of us who live in northern climes, and especially before the industrial revolution, the winter solstice is the scariest time of the year. The light is getting less and less, and the weather is getting worse and worse, and all in all, this is the time of year when winter officially declares war on humanity. Winter comes around every year. It kills the sick and weak. It makes important activities like travel and agriculture impossible. It makes even basic activities, like getting water, washing things, bathing, and going to the bathroom anywhere from inconvenient to actually dangerous to do without freezing to death. If winter never went away, then we would all surely die. That is a grim but undeniable fact. Read To Build A Fire by Jack London, and tremble.

Thus, people’s vulnerability before winter is both an instance and a symbol of our vulnerable position before all the hardships and dangers in this fallen world, including the biggie, death. And including, because of death, grief and sorrow.

Yule is a time of dealing with these realities and of waiting for them to back off for another year. After the solstice, the days slowly start getting longer again. The light is coming back. Eventually, it will bring warmth with it. Eventually, life.

Thus, it is entirely appropriate that when the Germanic tribes became Christians, they picked the winter solstice as the time to celebrate Jesus’ birth. He is, after all, the light of the world. A little, tiny light – a small beginning – had come into the bitter winter of the sad, dark world, and it was the promise of life to come. The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it. All this biblical, very Hebrew symbolism answers beautifully the question raised by the European pagans’ concern with the sun coming back.

Our ancestors were not “worshipping pagan gods” at Christmas. They were welcoming Christ (who is the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob) into the heart of their culture. They were recognizing that He was the light, using terms they knew, which were Germanic terms, and this is not surprising because they were Germans.

So, if you want to make the case that no holidays are lawful for Christians except those prescribed in the Old Testament for Israel, be my guest. Try to find some Scriptures to back that up. And maybe you can. But you cannot make that case by accusing people who put up a Christmas tree of worshipping pagan gods. All you’ll do then is reveal yourself to be historically ignorant.

Sources

BBC, “Devon Myths and Legends,” http://www.bbc.co.uk/devon/content/articles/2005/12/05/st_boniface_christmas_tree_feature

Foster, Genevieve, Augustus Caesar’s World: 44 BC to AD 14, Beautiful Feet Books, 1947, 1975, Saturnalia on p. 56 ff.

Hannula, Richard, Trial and Triumph: Stories from church history, Canon Press, 1999. Boniface in chapter 9, pp. 61 – 64.

Puiu, Tibi, “The origin and history of the Christmas tree: from paganism to modern ubiquity,” ZME Science, https://www.zmescience.com/science/history-science/origin-christmas-tree-pagan/

Whatever Was Going On in Saudi Arabia?

Consider this article:

“Spectacular Images Reveal Mysterious Stone Structures in Saudi Arabia”

It’s on the Ancient Origins website, which compiles and presents a lot of fascinating stuff, but which also has many annoying ads. Sorry about that!

So, to answer my own question, I think that many of these structures could have just been houses. Particularly when we get circular or triangular structures facing or intersecting each other, they don’t look so different to me than the pit houses and kivas of Mesa Verde. The only difference would be that they are much older.

Consider: Saudi Arabia was once much more verdant than today (as was Egypt, evidenced by the erosion channels on the Sphinx). These structures seem to be very old (evidenced by the fact that some of them have been partially covered with lava flows). They could be habitations dating back to a time when the area was actually rainy (immediately post-Flood?). The stone walls, now fallen, could have been topped with domed or conical roofs made of a more perishable material.

“But they think the cairns in them contain burials!” True. It’s interesting that they only think this. Apparently, they haven’t been allowed to show up in person so as to excavate/investigate. These are sites I’d like to visit … except, of course, I’d rather the demons didn’t get me. Anyway … if the cairns do turn out to be burial mounds and not something more prosaic like ovens, even that wouldn’t be completely unprecedented. It might seem a little odd to have Grandpa buried right there in your family housing complex, but it has been done before, at least with ossuaries (bone boxes). The cairn would become a sort of ancestral shrine. It’s not unheard of in human history.

So, About that Pure Democracy

[A] pure democracy, by which I mean a society consisting of a small number of citizens, who assemble and administer the government in person, can admit of no cure for the mischiefs of faction. A common passion or interest will, in almost every case, be felt by the majority of the whole; a communication and concert result from the form of government itself; and there is nothing to check the inducements to sacrifice the weaker party or an obnoxious individual. Hence it is that such democracies have ever been spectacles of turbulence and contention; have ever been found incompatible with personal security or the rights of property; and have in general been as short in their lives as they have been violent in their deaths.

James Madison, Federalist No. 10

More Federalist Realism

There are again two methods of removing the causes of faction: the one, by destroying the liberty which is essential to its existence; the other, by giving to every citizen the same opinions, the same passions, and the same interests.

It could never be more truly said than of the first remedy, that it was worse than the disease. Liberty is to faction what air is to fire, an aliment without which it instantly expires. But it could not be less folly to abolish liberty, which is essential to political life, because it nourishes faction, than it would be to wish the annihilation of air, which is essential to animal life, because it imparts to fire its destructive agency.

The second expedient is as impracticable as the first would be unwise. As long as the reason of man continues fallible, and he is at liberty to exercise it, different opinions will be formed. As long as the connection subsists between his reason and his self-love, his opinions and his passions will have a reciprocal influence on each other … The latent causes of faction are thus sown in the nature of man.

James Madison, Federalist No. 10

Misanthropic Quote: Against Utopianism

Have we not already seen enough of the fallacy and extravagance of those idle theories which have amused us with promises of an exemption from the imperfections, weaknesses, and evils incident to society in every shape? Is it not time to awake from the deceitful dream of a golden age, and to adopt as a practical maxim for the direction of our political conduct that we, as well as the other inhabitants of the globe, are yet remote from the happy empire of perfect wisdom and perfect virtue?

John Jay, Federalist No. 6