Quick! Who do we know who’s a linguist, a former missionary, a gifted writer, and wants to capture in novel form the human condition and God’s grace to us in it?

Who is awkward, reserved, and can come off as rude and abrupt, but actually has passionate emotions, a deep love for others, and a rich inner life?

Who loves nature? Crosses cultures happily, but doesn’t fit in so well in the American evangelical context? Who has a secret desire to be admired, but also suffers from poor judgement about the opposite sex?

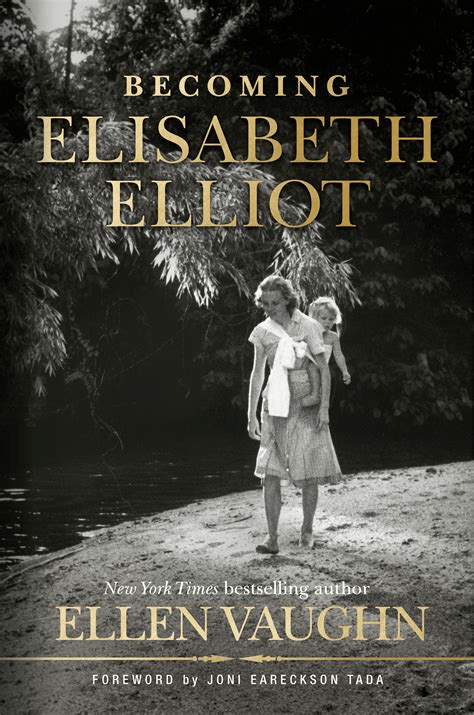

Why, Elisabeth Elliot, of course!

Me and Elisabeth Elliot

When I was college and just discovering the things I ranted about last Friday, like the fact that we as a culture could use some guidelines about the how the sexes ought to relate to each other, I came across Elisabeth Elliot’s book Passion and Purity. I devoured it.

This book was exactly suited for me at the time. I was just starting to grow in Christ. I really wanted to do God’s will. I also, unbeknownst to me, had a lot in the common with the author of Passion and Purity: socially awkward, ascetic tendencies, perfectionistic, a longing for old-fashioned values. This book is basically about the lessons Betty, as she was called at that time, learned during her five years (!) of waiting for Jim Elliot to make up his mind that God had given him the go-ahead to marry her. Their courtship story strikes many Christian young people as really spiritual upon first hearing, and then on a second look, it starts to look as if he didn’t treat her very well possibly. But I bought into it fully.

Anyway. Full of missionary zeal to win other young people over to the idea of an extremely awkward, chaste, long courtship, I gave this book to a friend. She read it, and her reaction was, “There are the Elisabeth Elliots of this world, but I am not one of them.”

That annoyed me at the time (someone had rejected my idealistic ideal!), but from my perspective now, that friend of mine didn’t know how right she was. In fact, not even Elisabeth Elliot herself was one of the Elisabeth Elliots of the world, at least not in the sense of having perfect wisdom and self-control. At the time she was writing this (early 1980s), Elisabeth was enduring an extremely controlling marriage with a man she married because she didn’t want to be lonely. She stayed with him for the rest of her life, despite an intervention by her family. It’s chilling to realize that the woman who wrote Passion and Purity could make such a foolish decision.

Before Passion and Purity, I remember as kid seeing black-and-white photos of Elisabeth toting her small daughter Valerie into the jungle to serve the Waorani people (then called the Auca), a few years after her husband Jim was killed by them. These were the photos taken by Hungarian photographer Cornell Capa. They, and the books Elisabeth wrote about the Waorani, had made her and her martyred husband Jim famous throughout the evangelical world.

Both greater and lesser than I thought

When you think you know a story, you expect it to be boring. I put off for some time reading this duology by Ellen Vaughn, until it finally floated to the top of my reading list. Once I opened the books, I found that I couldn’t put them down. Vaughn is an excellent researcher and a vivid and sympathetic writer, and though I had read a number of books by and about the Elliots, I certainly didn’t know as much of their story as I thought.

Vaughn, aware that she is telling a story the outlines of which are familiar to readers, moves skillfully back and forth through time, as in a novel (though in rough outline, the first book deals with Betty’s early life and the second book with her post-Ecuador years). Vaughn doesn’t try to tell every story–there are too many, many of which have been told elsewhere, and others of which are apparently too private and will stay hidden forever in Elisabeth’s prolific journals. In fact, as I read these books, I felt I was getting to know two fellow woman writers: Elliot and Vaughn.

When you are a former missionary, it’s difficult to read other missionaries’ stories without comparing them to your own. Usually, this means you are reading about people who were far ahead of you in dedication, selflessness, toughness, and in what they suffered. This is certainly true of the Elliots. At the same time, so much of their personalities and stories seemed shockingly familiar. For example, young Jim Elliot was, besides being a great guy, an insufferable holier-than-thou know-it-all, of the “I’m going to go read my Bible” type. Betty, as Elisabeth was then called, was quiet and reserved and often didn’t realize that she was coming off as standoffish. Jim’s family verbally eviscerated her after her first visit to their home in Portland, and foolish young Jim passed all these criticisms on to Betty in a letter. She was devasted, but thought and prayed over the things they had said, and then concluded that none of them were things she could actually change. Later, Jim couldn’t believe he had shared his family’s words with Betty. As Bugs Bunny would say, “What a maroon. What an imBAYsill.”

They were just people, you see. Not angels. Which means that “just people” can always serve God.

Jim Elliot, you beautiful dunce.

The things they suffered also rang poignantly familiar. They suffered setbacks that lost them a year of their work–for her, language work; for him, building a mission station. Neat and tidy Elisabeth at some points had to live in squalor, and felt guilty for the fact that it bothered her. Fellow missionaries (not all) and Waorani Christians alike (not all) proved manipulative and controlling. In fact, it was relationship difficulties that caused Elisabeth eventually to leave the Waorani, after spending only a few years with them. This was not Elisbeth’s fault: person after person found it impossible to work with Rachel Saint, her fellow translator. But she took on as much of the responsibility for it as she possibly could, agonizing before God in her journals, because that was the kind of person she was.

Elisabeth the Novelist

Now we are getting into events of the second book, Being Elisabeth Elliot. Elisabeth knew that she had a gift of writing. She had made so much money from her books Through Gates of Splendor and The Shadow of the Almighty that she was able to build a house for herself and her daughter near the White Mountains of New Hampshire (talk about living the dream!) and settled down to become a writer. She really wanted to write great literature, the kind that would elevate people’s hearts and give them fresh eyes to see the great work of God all around them in the world.

If I were writing a novel about Elisabeth Elliot, I would end it there, and let her have a period of rest, in the beautiful mountains, with her daughter, writing her books, for the rest of her days. I wish that was how it had gone. I kept hoping, as I read this duology, for there to come a point when Vaughn could write, “And then, she rested.” Alas, that moment never came.

Elliot was indeed a really good writer. Sometime in the twenty-teens, when I was a young mom who had come back from the mission field hanging my head over my many failures, and had unpacked my books and settled into a rented house to minister to my small children, I found on an upstairs shelf a slim volume that looked as if it had been published in the 1960s or 70s, called No Graven Image. This was the novel that Elliot wrote when she first settled down in New Hampshire. She wished, through fiction, to give her readers a more powerful, truer picture of missionary life than her biographies had done.

This is not the cover my copy of the book had, though it also had an image of a condor.

No Graven Image was not well received when it came out. It was the old problem of marketing. To what audience do you market a genre-bending book? The people who liked to read tragic, worldly novels were not interested in a so-called “novel” about a young missionary woman, probably expecting that it would be preachy. The Christians who liked to read missionary stories were shocked and dismayed by a novel in which the protagonist flounders around, makes mistakes, and ultimately, accidently kills her language informant when he has a bad reaction to a shot of penicillin. And then decides that her desire to have a successful language project had been a form of idolatry.

Some readers appreciated the novel (particularly overseas missionaries), but most found it shocking, even blasphemous. They wanted a triumphant novel, not the story of Job. They wondered whether Elisabeth had lost her faith.

When I picked it up, in the twenty-teens, it made me feel extremely understood.

One thing that killed me as I read of Elisabeth’s later years is that this was the only novel she wrote. She very much wanted to write others, and she got as far as making notes for another novel. But life (read: men) intervened, and she was in demand for speaking and for writing nonfiction books such as Passion and Purity. She wasn’t able ever again to get the extended periods of time to concentrate that it would have taken to gestate a novel. She convinced herself that she just didn’t have what it took to write actual good fiction (and perhaps, that it was selfish to try). I am so sad to watch this dream die. I believe that she would have been a good novelist. I don’t know whether her publisher would have kept publishing her books if she had turned to fiction, or whether she would have had trouble finding another publisher. Spiritual non-fiction was what she had already become known for. She probably would have made less money, perhaps found it difficult to support herself. But still … you know … it’s hard to watch. So many things about the second volume of her biography are hard to watch. At the same time, because of Vaugh’s amazing research and writing, it’s hard not to sit back and just stare at this major accomplishment.