“Why do you think anyone would want to read about you?” I asked.

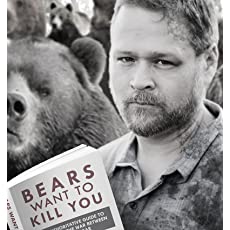

“I’m a detective. People like reading about detectives.”

“But you’re not a proper detective. You got fired. Why did you get fired, by the way?”

“I don’t want to talk about that.”

“Well, if I was going to write about you, you’d have to tell me. I’d have to know where you live, whether you’re married or not, what you have for breakfast, what you do on your day off. That’s why people read murder stories.”

“Is that what you think?”

“Yes!”

He shook his head. “I don’t agree. The word is murder. That’s what matters.”

Anthony Horowitz, The Word is Murder, 2018, p. 25

The blurb on the back of this book calls it a “meta-mystery,” and that’s a perfect description. It is so, so meta.

Horowitz writes about himself, Anthony Horowitz, the guy who has created the TV series Midsomer Murders and Foyle’s War and who has written a popular series for kids, and is now trying to break into the adult market. He has just published The House of Silk, a Sherlock Holmes novel in the style of Conan Doyle. He’s approached by this ex-detective, Hawthorne, who still sometimes does consulting work for the local police force. Hawthorne’s idea is that Horowitz will follow him around as he investigates, turn the investigation into a crime novel, and make both of them rich and famous. The problem is that the investigation has just begun, and it’s unknown whether Hawthorne will solve it and, if so, whether it will have a satisfying ending. Also, though Horowitz naturally has to be present while Hawthorne interviews suspects, he is under no circumstances supposed to interrupt, ask his own questions, or contribute in any way. If Hawthorne misses something due to one of these interruptions, it’s Horowitz’s fault.

But How Meta Is It, Really?

I still don’t know how much of this novel is truth and how much is fiction. I think the whole thing is made up. But references to Horowitz’s past books and TV shows, and his descriptions of the industry, seem to be real.

There’s a very funny, agonizing scene where Horowitz is in a meeting with Peter Jackson and Steven Spielberg to show them the script he’s written for a planned second Tintin movie. He’s been working on the script for months, and he’s feeling excited as well as startstruck to be in the same room as Spielberg. But Spielberg abruptly tells him that the Tintin book he has turned into a script is the “wrong” book, even though that’s the one he and Jackson had agreed to use. Into this tense moment, Hawthorne bursts in. He fails to recognize Spielberg, but recognizes Jackson and compliments him. He then insists that Horowitz leave with him. The directors insist that Horowitz leave too, saying they will call him back, which they never do.

That sounds awfully realistic, even if it didn’t happen with Hawthorne. Even if there is no such person as Hawthorne. There is also no such person as Damian Cowper, the British movie star, recently relocated to Hollywood, who is at the center of the mystery.

So, on the whole, I think this actually is, as they say, a “fiction novel,” weaving in nonfiction glimpses into Horowitz’s career, modern London, and the conditions in the publishing and movie/TV industry. Horowitz’s insights about writing and marketing his work are enjoyable. And the novel is extremely professionally written. The characters, the writing itself, the clues, and the satisfying nature of the mystery all show that Horowitz has been writing mysteries for many years.

The Tintin Rant

I do have to take one side trip to rant about a rant of Horowitz’s. If you will pardon a long quote:

Tintin is a European phenomenon and one that has never been particularly popular across the Atlantic. Part of the reason for this may be historical. The 1932 album, Tintin in America, is a ruthless satire on the United States, showing Americans to be vicious, corrupt and insatiable: the very first panel shows a policeman saluting a masked bandit who is walking past with a smoking gun — and no sooner has Tintin arrived in New York and climbed into a taxi than he finds himself being kidnapped by the Mob. The entire history of Native Americans is brilliantly told in five panels. Oil is discovered on a reservation. Cigar-smoking businessmen move in. Soldiers drive the crying Native American children off their land. Builders and bankers arrive. Just one day later, a policeman tells Tintin to get out of the way of a major traffic intersection. “Where do you think you are — the Wild West?”

The Word is Murder, p. 148

Side eye.

O.K., Mr. Horowitz.

First of all, I can tell you the exact reason Tintin isn’t popular in the United States: It’s just not available. Oh, sure, it’s available now. Now we can get anything, with the Internet. But when I was a kid, there was just nowhere in the U.S. that you would see Tintin albums for sale. I was first exposed to them because we knew a family who had lived in Europe for a time, and once we knew of his existence, my siblings and I enjoyed Tintin just as much as any kids would. The same goes for Asterix and Obelix, by the way. It’s still kind of difficult to get good-quality A&O albums. When I tried to buy some for my kids, one arrived with the pages falling out.

Secondly, it never occurred to me, reading Tintin in America in the 1990s, that it was a “vicious satire” of America. I just figured it was all the silliest and most extreme stereotypes about America, which is the same treatment that Herge gives pretty much every country he portrays. And, the idea that Americans would be shocked by this portrayal? I don’t know, maybe in the 1930s. But this generation Xer would like to point out that gangster movies are one of our most beloved film genres, and that we are taught from knee-high about the injustices done to the Native Americans (besides many films and books being made about same). And in fact, Herge’s portrayal of the way the Indians talk would not be considered acceptable in America today. So, yeah, Mr. Horowitz, I realize you are very smart British author — and it’s obvious from your craft that you are smarter than I will ever be — but I think you may have overestimated Americans’ provinciality just a tad, while also underestimating our IQ.

The Detective

The best thing about this book, in a way, is the detective, Hawthorne. He is also the most unsatisfying thing. He never does allow Horowitz to get to know him. He really does prove to be brilliant, and Horowitz sort of ends up playing Hastings to Hawthorne’s Poirot. This is all the more frustrating for Horowitz (and for the reader) because Horowitz is not dumb and he knows it. He’s an adult with a good career well underway, and he knows his way around a mystery novel. He just hasn’t had direct experience with real-life investigating.

Hawthorne is the sort of person that all of us have had to work with at one time or another. He comes off as unwittingly controlling, always telling Horowitz his business. He doesn’t like the title “The Word is Murder,” for example. He wants it to be “Hawthorne Investigates.” (Spielberg and Jackson back him up.) He doesn’t like the way that Horowitz sets the scene in the first chapter. Although not a writer, he thinks that Horowitz should methodically introduce every detail that Hawthorne would notice, without any atmosphere or description. He gives advice about choice of words. Whenever Horowitz objects “But I’m the one you asked to write it!”, Hawthorne says something like, “Hey, don’t get all upset! I was just trying to help.”

This is the kind of person that you cannot be around for very long. Unless you are pathologically conceited, all their “help” can’t help but make you doubt yourself. Although we cannot work long-term with such a person, it is nice to see one portrayed in fiction (if this … is … fiction?). It lets us know that even pros like Horowitz have had the same experience.