Me: So, the Latin verb mereo means “I earn or deserve …” (heading towards the derivatives merit and meritocracy)

Third grader, way ahead of me: Is that why it’s called “marriage”?

Me: So, the Latin verb mereo means “I earn or deserve …” (heading towards the derivatives merit and meritocracy)

Third grader, way ahead of me: Is that why it’s called “marriage”?

Last week, I lost my voice for four days. (Actually, as I write this, it is Day 5 and my voice is coming back occasionally, fading in and out like an AM radio. By the time this post goes up, it will be “last week.”)

I didn’t even feel sick particularly. I had taken a shower, then gone outside with a hat over my wet hair to move my chickens into the garage because the temperatures were in the negatives. Turns out Grandma was right: don’t go outside with wet hair. By about 48 hours later, my voice was getting froggy, and the next day, it was gone.

I’m a Latin teacher. You see my dilemma.

I had always disliked talking to people (nearly always women) who whisper everything they say. Unless there is a baby sleeping in the house, these women always gave the impression that they were so much more elegant, refined and nice that I could never hope to compete. (And I couldn’t. I am naturally blunt, with a rich, resonant, rather loud speaking voice.) Now I was one of them. For the first day or two, I couldn’t make myself heard at all. After that, if I really forced the air out, I would sound like a tracheotomy patient … or like our President when he’s about to make what he considers a really telling point.

The first thing I found out is how terrific my students are. They happily complied with me teaching by mime. They helped read passages out loud to one another. They were far, far more cooperative than usual.

I know that someone is immediately going to make the point that this is why I should lower my voice to a whisper whenever the classroom becomes loud. Yeah, yeah, yeah. The problem with that is that is that you have to keep it up for quite a while before it starts working. Also, I don’t like to inflict a raspy whisper on my interlocutors as a matter of course. It sounds, frankly, unpleasant.

I actually had to whisper a lot more to my family at home than to my students at school. So much of what happens in the classroom is based on routines and chants that they already know. All I had to do was indicate the chant or poem or verse, and they could say it. At home, things are more organic. Needless to say, my family found the whisper unpleasant.

Second point: The instinct to match your interlocutor in tone and volume is really, really, strong. My students tended to whisper back to me, even though they knew they did not need to. Anybody I encountered in public, such as at the library or the diner, tended to do the same. Many of them, by the way, clearly found this annoying, which leads to the third discovery: I’m not the only one who feels shushed by people who whisper.

I hope you all don’t mind this personal-story post. I enjoy reading personal stories by the bloggers I follow from time to time.

My vision is crowded with whispers and movement and strange shapes narrowing in. I feel my heart thudding in my chest, the sweat flowing freely in my hair, under my arms.

Something inside me breaks. I close my eyes and open my mouth, and a piercing scream tears out of me. The scream relieves the pressure in my head, and it feels so good that I scream again.

“It’s there!” I jabber, lurching in my seat. “I see it there! Goody Corey’s yellow bird sits on Reverend Lawson’s hat! I see it plain as day, the Devil’s yellow bird sits on the Reverend’s hat!”

Conversion, p. 362 – 363

I picked up this book from the public library, among a few others, to have fiction to read over Christmas break. After one false start (a high-school drama that was unable to hold my attention), I cracked open Conversion, and it was a winner.

Here’s the blurb from Howe’s website:

A chilling mystery based on true events, from New York Times bestselling author Katherine Howe.

It’s senior year, and St. Joan’s Academy is a pressure cooker. Grades, college applications, boys’ texts: Through it all, Colleen Rowley and her friends keep it together. Until the school’s queen bee suddenly falls into uncontrollable tics in the middle of class.The mystery illness spreads to the school’s popular clique, then more students and symptoms follow: seizures, hair loss, violent coughing fits. St. Joan’s buzzes with rumor; rumor erupts into full-blown panic.

Everyone scrambles to find something, or someone, to blame. Pollution? Stress? Are the girls faking? Only Colleen—who’s been reading The Crucible for extra credit—comes to realize what nobody else has: Danvers was once Salem Village, where another group of girls suffered from a similarly bizarre epidemic three centuries ago . . .Inspired by true events—from seventeenth-century colonial life to the halls of a modern-day high school—Conversion casts a spell.

The story goes back and forth between modern St. Joan’s and 17th-century Salem. The excerpts from Salem are fairly long. I would say they take up a quarter to a third of the book. The Salem storyline is told from the perspective of Ann Putnam, one of the “afflicted” girls who, years later, made a public apology which stated that she now thought the people accused of witchcraft had been innocent.

Coming into this, I wasn’t sure I would finish it. Books about the Salem witch frenzy, after all, can easily go sideways into facile Christianity / patriarchy bashing. And at first, it did look like Howe was implying that: It’s suh-sigh-uh-tee! These girls had no pow-er! Some of them were servants! The first person they accused was a slave! However, Howe never veered into caricatures. She painted a fairly complex picture, held the girls also responsible, and the writing was good enough that I ended up finishing the book.

I do think Howe’s interpretation of what went down would be more feminist than my own. In the Salem scenes, the men are, to a person, cold, harsh, and uncaring as fathers. (Also, the women can’t read.) However, in the Danvers scenes, Colleen has loving, involved parents who are still married, a kindly younger brother, an apparently goodhearted boyfriend, and a priest at her school who seems like a good egg. The pressure on the Danvers girls comes more in the form of an academically competitive environment where they are all hoping to get into Ivy League colleges. In fact, the fact that none of the girls’ parents seem to be divorced is striking.

Howe’s diagnosis of the St. Joan’s girls – and, apparently, of the Salem girls also – is a medical phenomenon called conversion, whereby intense mental stress is “converted” into bizarre physical symptoms.

In the case of the Salem girls, as Howe tells it, it begins with one little girl who genuinely takes sick with what used to be called a nervous breakdown. It’s implied, but never drawn out, that she has been abused by her father. The phenomenon is then taken up by a servant girl living in the same house who is clearly faking at first, for attention and to get out of being worked hard. She even bites herself on the arm to manifest mysterious wounds. The phenomenon then spreads through a combination of this particular girl enjoying the attention; other girls being unwilling to speak up but just saying what they think the adults want to hear; possible suggestion as the girls work themselves into a genuine state; and simmering resentments in the town, as the girls and their parents use the trials to get revenge on those they envy.

In the case of the St. Joan’s girls, Howe is able to offer medical explanations for even the most bizarre physical phenomena. For example, one girl who has been coughing up pins turns out to have pica (a mineral deficiency that causes a compulsion to eat things that are not food, such as dirt). You see, there is a medical explanation for everything!

This book was published in 2014 and the modern-day story is set in 2012. Now, since the Plandemic, Howe’s trust of the medical establishment struck me as naive and dated. The Department of Public Health is the voice of sanity in the St. Joan’s hysteria, and it’s they who figure out that conversion (not the HPV vaccine or environmental pollution) is what’s causing it. Near the end of the book, when the phenomenon has been taken care of by these experts, Colleen narrates that “We are all on the same antidepressant.” This is a red flag to anyone who’s familiar with the research about how harmful behavioral meds can be to kids and teenagers, and how they have been chronically overprescribed, often for way too long at a time, and what a huge moneymaker they are for pharmaceutical companies. I have only a very basic, passing familiarity with this stuff, and even I was concerned. But Howe seems to believe in The Science just as firmly as the Puritains believed in The Devil.

Nevertheless, Howe draws back from explaining away the strange phenomena completely. There’s an odd scene near the end of the book when Colleen’s best friend’s mother, who is always described as pale blonde, ghostly, suffering from migraines, and almost never leaving her house, pulls Colleen into a dark corner and whispers creepily that her daughter is “like me.”

“She’s prone to spells. But it can be managed. Helps to have the family close by. I’m only telling you so you don’t have to worry.”

My mouth went dry.

“But how did you –” I stopped, because it almost seemed as though her eyes were glowing faintly red.

“Anyhow,” Mrs. Blackburn said, her smile widening, a tooth glinting in the darkness under the stairs, “They said what caused it, in the news. Didn’t they.”

“Y — yes.” I swallowed.

“Good. So there’s no problem.”

The hand released my wrist.

ibid, p. 393

I’m not sure what the purpose of this creepy scene is. Is Howe trying to buy back the “mystery” element of her book, even though by that point in the story, all the explanations have been offered? If she is trying to keep the story somewhat paranormal, I’d say the attempt is not successful. Nothing else that happens in the book, not even the scenes in Salem, hint that any actual paranormal activity might be going on. It is all just the girls’ minds deteriorating. Or is Howe trying to imply that Mrs. Blackburn is displaying Munchhausen by Proxy and is somehow making her own daughter sick? If that’s the theory, it’s way too late in the novel to introduce it, and it never gets further explored. There does seem to be a longer version of this book (“not condensed”) out there. Perhaps the Mystery of Mrs. Blackburn is explained in the longer version, but in the book I read, it just comes off like the author wants to add complexity even though she clearly believes the Harmless Medical/Societal Pressure Explanation.

I do not know enough about the Salem witch trials — or witch trials in general — or even the Puritains, although I have read some of them — to speak authoritatively about the degree to which Howe’s explanations are correct. Howe has done a lot of research about the Salem trials, and even includes long excerpts from the transcripts in her novel. It’s not clear, however, whether she has done much research about other witch trials in New England (or Old England), or about Puritan theological beliefs.

Fortunately, I have a book by someone who has.

When you read a lot, serendipities sometimes happen. I bought this book many, many years ago, at a used book shop in Kansas City, when I was there for a vacation with extended family. My dad has Used Bookstore Radar, and he always likes to visit the used bookstores whenever he is in a strange city. So I went with him and bought my own armload. This book was an impulse buy that survived several rounds of elimination, because Salem was one of those historical topics that I “really needed to learn more about.” Well, now the time has come.

John Putnam Demos, interestingly, found out only after he had begun witchcraft research that he is descended from the Putnams, the family who were instrumental in many of the witchcraft convictions in Salem.

I’ve only begun the book, but here is what I can tell you. Although Salem has become famous for cases getting out of hand, witchcraft (“entertaining Satan”) was a recognized crime during the 1600s, on both sides of the Atlantic. As with other crimes under English common law, any accusation had to be first investigated informally, and many of these were settled without going to court, which means we have no official records of them. If the stage of going to court was reached, there were still legal proceedings, evidence presented, and so forth, and the magistrates could and often did acquit the accused or void the case on a technicality. People who had been accused of witchcraft could also sue their accuser for slander. Some countries, and some regions of each country, prosecuted people for witchcraft far more often than others.

It is this background of which Demos wants to draw a detailed picture. He tells us that he is going to look at the biographical details of certain accused and accusers. He is going to look at this from a sociological, psychological, and historical point of view. I am sure I will learn a lot from him. But, when it comes right down it, Demos is still studying witch trials as a sociological phenomenon. He is not examining whether the paranormal may have played an actual role.

Possibly the most annoying scene in Conversion is when Colleen’s teacher, Ms. Slater, tells Colleen that a good historian should “look beyond the dominant narrative” about Salem. I’m not certain what Slater thinks the “dominant narrative” about the Salem witch trials is. Surely, in modern times, most people see nothing more than a story of injustice and superstition played out in an overly rigid, hierarchical society. That’s certainly not the narrative that was dominating in Salem at the time. The only way I can detect that Slater’s preferred emphasis differs from the dominant modern narrative, is that she wants us to have more sympathy for the teenaged girls who were doing the accusing, for the pressure they were probably under.

This is actually a new thought. If I may speak from my own experience, when we read accounts of the trials, the girls definitely come off as the villains of the piece: screaming accusations, making their adult victims cry. The tendency is to attribute malice. I wouldn’t say that comes from listening to a narrative told by people in power, though; rather, it’s the immediate first impression that we get from just observing their behavior.

By contrast, here’s how Ann Putnam’s experience went down in Conversion:

“Oh, Annie, tell them how we suffer!” Abigail beseeches me.

“I … I …” I stumble over my words, terrified. If I continue the lie, I’m sinning in the eyes of God. A vile, hell-sending sin. If I speak the truth, I’ll be beaten sure, and all the other girls will, too. My mouth goes dry, and bile rises in my throat.

At length, I whisper, “I cannot say whose shape it is.”

page 221

And here:

I’m beginning to panic, and I want to get up and run away [from the courthouse] and hide in the barn behind our house, but everyone is there and everyone is watching me, and my father is there and I have to stay strong and do what they want me to, and so I stay where I am, making myself small on the pew, and soon enough the tears are springing from my eyes, too.

page 258

The picture here is of a girl trapped in a story she knows there is something wrong with, but afraid to out her friends and to displease the adults. This is also very plausible. It reminds me of so-called “trans” children, trapped in an even more harmful delusion foisted upon them by the adults in their lives and by their peers, manipulated into believing this is what they themselves want and have chosen. This could have been one of many factors operating in Salem. This is how social contagions work. There is a big lie; there are vulnerable, confused children or teenagers; there are culpable adults and confused adults; there is social pressure; there is mass deception.

So let’s look at some factors, remembering that many things can be true at once.

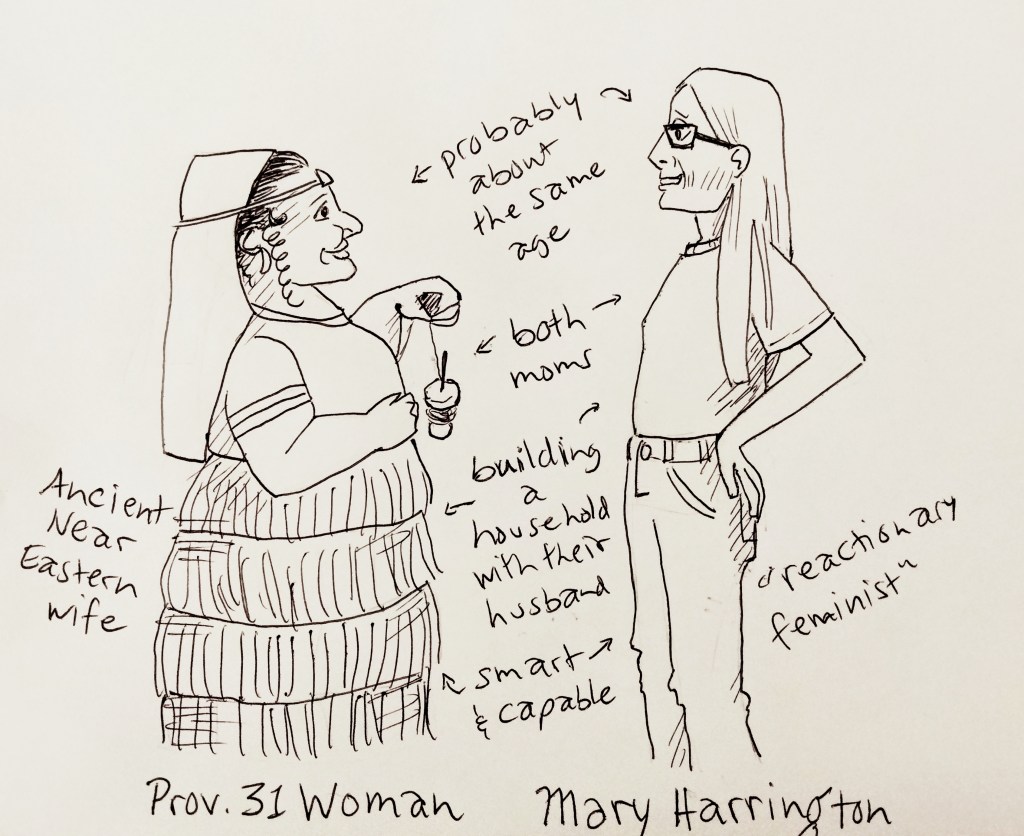

This is Mary Harrington. She has written a book, and here it is:

Mary is an academic. She describes herself as someone who has “liberalled as hard as it is possible to liberal.” She believed all the lies that were told her by the sexual revolution, and though she has no desire to share the details, says her experience of it was comparable to that of Bridget Phetasy, with her famously heartbreaking article, “I Regret Being A Slut.”

As you can see from the phrase that makes “liberal” into a verb, Mary has quite the way with words. The basic thesis of her book is that the progressive religion, by making personal autonomy the only definition of the good to which everything else must be sacrificed, has gone way past the point of diminishing returns and is now actually harming women rather than helping them. But since Mary is so articulate and fiery, she can put it far better than I can:

We’re increasingly uncertain about what it means to be [sexually] dimorphic. But when we socialise in disembodied ways online, even as biotech promises total mastery of the bodies we’re trying to leave behind, these efforts to abolish sex dimorphism in the name of ‘human’ will end up abolishing what makes us human men and women, leaving something profoundly post-human in its place. In this vision, our bodies cease to be interdependent, sexed and sentient, and are instead re-imagined as a kind of Meat Lego, built of parts that can be reassembled at will. And this vision in turn legitimises a view of men and women alike as raw resource for commodification, by a market that wears women’s political interests as a skin suit but is ever more inimical to those interests in practice.

What we call ‘feminism’ today … should more accurately be called ‘bio-libertarianism,’ [and it is] taking on increasingly pseudo-religious overtones. This doctrine focuses on extending individual freedom as far as possible, into the realm of the body, stripped alike of physical, cultural or reproductive dimorphism in favour of a self-created ‘human’ autonomy. This protean condition is ostensibly in the name of progress. But its realisation is radically at odds with the political interests of all but the wealthiest women — and especially those women who are mothers.

… nothwithstanding the hopes of ‘radical’ progressives and cyborg feminism, a howlingly dystopian scenario can’t in fact be transformed into a dream future just by looking at it differently.

ibid, p. 17, 18, 19

I mean, I couldn’t agree more. The most obvious people to suffer from the real-life application of what Mary elsewhere calls “Meat-Lego Gnosticism,” are children. Babies and children need their moms. In fact, Mary’s thinking began to really change on this topic of progress when she had a child of her own and was shocked by the instant bond.

But even a little bit of thought shows that women are also suffering, because most women, like Mary, actually want to bear and raise their own children, preferably in a household with the child’s father. And, in fact, men are suffering too, not only because half of those motherless children grow up to be men, but because it turns out that humans were made to be embodied, and so living a disembodied life, alienated from our physicality and from human relationships, makes all humans miserable.

Mary calls herself a “reactionary feminist” because she is reacting against “progress” in favor of the interests of women.

Often, when people reject progressive feminism, the only alternative that they hear presented is “traditional marriage,” by which they mean the 1950s sitcom model. But that model is actually not traditional marriage so much as postindustrial marriage.

Harrington spends a lot of space in the book pointing out how, with industrialization, many of the homesteading tasks that were once the responsibility of the housewife got outsourced to the market. She draws on Dorothy Sayers for this, who pointed it out a long time ago in her essay “Are Women Human?” I wanted to quote Sayers directly, but don’t have a copy of the essay on hand. Essentially, she says that before the industrial revolution, women got to do milking, cheesemaking, beer brewing, baking, spinning, weaving, sewing, mending, and a number of other arts and crafts that took quite a lot of skill and are also fun. Sayers’ main point is that, in the wake of all these trades being moved out of the household, it is no wonder that middle- and upper-class women are bored and would like to do something other than sit around the house. Harrington’s application of this point is a little different. She points out that in economic terms, before industrialization a wife contributed really essential labor to the household. A husband could not get along economically without her. Because both spouses were committed to keeping the same ship afloat, the man was less likely to abandon the woman.

Post- Industrial Revolution, the woman (particularly in upper and middle classes) now contributed much less to the household economically. The man was the sole wage earner, which gave him a lot of economic power. He could treat his wife badly, and she’d have no recourse. It is to this shifting dynamic that Harrington attributes the rise of Big Romance. A husband and wife must like each other, must be madly in love, and then he will treat her kindly despite the imbalance of economic power.

I think Harrington’s analysis has merit, though it doesn’t tell the whole story. For example, I would argue that relations between men and women first got badly messed up at the Fall. Wife abuse was certainly possible before the Industrial Revolution. Also, I would argue that Big Romance owes something to the concept of Courtly Love in the Middle Ages, which in turn owes something to Paul’s exhortation to newly Christianized former pagans: “Husbands, love your wives as Christ loved the church and gave Himself up for her.” But all that said, I do think Harrington is on to something here. Obviously, when we are talking in broad strokes about the relationships between men in general and women in general, over centuries or millennia, there are going to be a ton of cultural and historical and literary and religious and yes, economic factors that go into it, even if we confine our survey to just the West.

So, if we don’t like Meat-Lego “feminism” and we don’t like 1950s Big Romance, what’s left? At this point, Mary’s book begins to have the feel of re-inventing the wheel. Metaphors abound that compare modern men and women’s situation to rebuilding, using broken tools, in a postapocalyptic wasteland. Mary doesn’t know a lot about what a life that is good for women, children, and men should look like, but she is pretty sure that for the majority of people, it’s going to be in families built on heterosexual marriage. And she’s aware that, to find a good model, we’ll have to go back before the Industrial Revolution.

Here’s what she comes up with.

The weakness of [proposals to go back to 1950s style marriage] isn’t that they’re unworkable, or even that they’re ‘traditional,’ but that they’re not traditional enough. For most of history, men and women worked together, in a productive household, and this is the model reactionary feminism should aim to retrieve.

Remote work, e-commerce and the ‘portfolio career’ are not without risks … But cyborg developments also offer scope for families to carve out lives where both partners blend family obligations, public-facing economic activity and rewarding local community activities in productive mixed-economy households, where both partners are partly or wholly home-based and work collaboratively on the common tasks of the household, whether money-earning, food production, childcare or housekeeping.

ibid, p. 179, 180

She then profiles two young women who are doing just that. Willow, in Canada, is a writer and mom to a small baby who, when childcare allows, also works with her husband on the family woodworking business. (He does the building, she does the finishing, basically.) Ashley and her husband, in Uruguay, have three children and do a mix of homesteading and language teaching.

In [Ashley’s] view, the romance comes not through the ego-fulfillment of a perfectly congenial partner, but working with someone to build something that will outlast them: ‘It’s much more romantic in the end when you realise this home, this life, these children, if they’re thriving it’s a result of our shared ability to create something greater together through our interdependence and cooperation … We’re working towards something bigger than ourselves. We’re building a legacy.’

Isn’t this a rather bleak and utilitarian view of a long-term relationship, though? To this I can only say that in my own experience, in practice the Big Romance focus on maximum emotional intensity and minimum commitment is bleaker. … A commons is, by definition, not available for consumption by anyone with the freedom to contract, or the money to buy, but only to those who share and sustain it.

ibid, pp. 183 – 184

What’s interesting about this vision of the household is that it has been described, not by “conservatives,” but by Reformed Christians, frequently, even within the past few years. Douglas Wilson, whom Mary Harrington has perhaps never heard of, has by now written a small library’s worth of volumes on this very topic. His daughter, Rebekah Merkle, has a book and a documentary about it, both called Eve in Exile.

And here, in his video Theology of the Household, Alistair Roberts lays out a view that is strikingly similar to the one in Harrington’s book:

Not surprisingly, these Christian thinkers are getting their picture of a household that is good for both men and women from … the Bible. And now I’d like you to meet Reactionary Feminism’s poster girl, and surprise! it’s not Mary Harrington.

A wife of noble character who can find? She is worth far more than rubies. Her husband has full confidence in her and lacks nothing of value. She brings him good, not harm, all the days of her life. She selects wool and flax and works with eager hands. She is like the merchant ships, bringing her food from afar. She gets up while it is still dark; she provides food for her family and portions for her servant girls. She considers a field and buys it; out of her earnings she plants a vineyard. She sets about her work vigorously; her arms are strong for her tasks. She sees that her trading is profitable, and her lamp does not go out at night. In her hand she holds the distaff and grasps the spindle with her fingers. She opens her arms to the poor and extends her hands to the needy. When it snows, she has no fear for her household, for all of them are clothed in scarlet. She makes coverings for her bed; she is clothed in fine linen and purple. Her husband is respected at the city gate, where he takes his seat among the elders of the land. She makes linen garments and sells them, and supplies the merchants with sashes. She is clothed with strength and dignity; she can laugh at the days to come. She speaks with wisdom, and faithful instruction is on her tongue. She watches over the affairs of her household and does not eat the bread of idleness. Her children arise and call her blessed; her husband also, and he praises her: ‘Many women do noble things, but you surpass them all.’ Charm is deceptive, and beauty is fleeting, but a woman who fears the Lord is to be praised. Give her the reward she has earned, and let her works bring her praise at the city gate.

Proverbs 31:10 – 31, NIV

Wow!

So, this is an older lady, a matriarch. She has children, and she is honored both by her husband, her children, and the public for her role as a matriarch. (Contrast this with Meat Lego feminism, where being a mom means you are dumb and irrelevant.) Perhaps this lady is beautiful, but we are not told that. In any case, she is an older woman, and “beauty is fleeting.” Her beauty has faded. But she has style (clothed in linen, purple, and scarlet). There is a lot of emphasis on her strength and capability. She engages in cottage industry, she has employees (servant girls), and she handles money and gets into real estate. She speaks with wisdom and faithful instruction, which probably primarily is directed at her children, but this could include her mentoring younger women and nowadays it could include being a writer like Willow. Her husband is a pillar of the community, and this is not to the exclusion of his excellent wife, but because of her and because of the kind of household they have built together. She, too, is known in the community and opens her hands to the poor. They are the people you go to if you need advice or help.

And, finally, this lady is not meant to be an outlier. “Many women do noble things, but you surpass them all.” The idea is that there are a lot of amazing women out there, but every husband should feel this way about his wife, that she is the best. The Prov. 31 woman is an older matriarch, so she has had time to build up an impressive portfolio of skills and accomplishments that for many young moms is years away. But this is where they can end up, if they are given support and honor in their role as moms and are shown what is possible.

In other words – I wouldn’t make this a headline without context as it would be misunderstood, but — the Prov. 31 Woman is the original Girl Boss.

Wow. This was devastating. It shows exactly how, not only the weird Christian subculture created by Bill Gothard, but the patriarchy and Christianity itself, which supports it, create an environment where sexual abuse and cover-ups are rampant.

Just kidding. That’s what the media desperately wanted this book to say. And because it doesn’t, that’s why they are going to call this book just another cover-up. In a moment, I’ll address the claims in the paragraph above. But first, what is this book actually?

I would say the book has two goals. One, it’s a memoir. Two, it tackles head-on the false teaching offered by Bill Gothard’s Institute in Basic Life Principles, and distinguishes it from the true Gospel. These two purposes are woven together in a very natural way in this book.

In case you didn’t know, Jinger was one of the Duggar family. They were a Christian family who, partly because of the teachings of Bill Gothard, came to the conviction that it is wrong to use birth control of any kind. Now, some families who make this decision only end up with a few children. But the Duggars ended up having nineteen. Later, they were approached about making their family the subject of a reality show, and after praying about it, decided to do it. They did not expect that the show would continue for ten years. Part of their rationale for agreeing to do the show was that they believed their family could be an example to the watching world of how following Gothard’s teachings leads to happiness.

Unfortunately, Gothard was, in retrospect, an obvious false teacher.

In the late 1960s, Gothard started teaching his seminars at churches, Christian schools, camps, and youth programs around the country. His timing could not have been better. For Bible-believing Christians, [the 1960s] were a scary, uncertain time. Parents feared losing their children to sex, drugs, and rock and roll. Bill Gothard offered parents confidence. In his lectures, he claimed that he had discovered the key to a successful Christian life. According to Gothard, to enjoy God’s blessing, a Christian should closely follow the seven principles he laid out in his seminars.

ibid, p. 26

Right away, Gothard displays several marks of a false teacher. The number one red flag is that he made himself indispensable to living the Christian life. He would find secret principles in the Bible that no one else had, and would identify unintentional sins that a person could commit that could wreck their entire life. Like a classic cult leader, he created fear in his followers (in this case, fear of accidentally displeasing God, which could lead to any number of bad consequences including death). Then, he offered himself as the solution to that fear. In other words, he was trying to take the place of Christ, the Bible, and the Holy Spirit.

I shouldn’t need to point this out, but Gothard was teaching what the Apostle Paul would have called “a different gospel.” In this case, it was the hoary old heresy of works righteousness, whereby a person can save themselves simply by following the right rules. Gothard didn’t seem to understand that sin nature is far too powerful to be restrained by rules. Nor did he understand the need for the new birth. It was a new insight to Jinger to realize:

Contrary to what I grew up believing, the ultimate threat to you and me is not the world. Instead, the ultimate threat to me is … me. I need freedom not from the influence of world, not even from a religious system, but from myself. I am born enslaved by my own sin.

ibid, p. 130

(Reformed folks call this idea “total depravity,” and it’s the first of the five theses in the TULIP acronym. Needless to say, Bill Gothard’s teaching was far from Reformed.)

Gothard also didn’t seem to think that God has revealed His plan of salvation clearly in the Bible, implying instead that God was a trickster who hides His will from people. Jinger gives many examples in this book of how Gothard would cherry-pick proof texts to support whatever point he was trying to make, but never taught straight through a long passage of the Bible, following the flow of thought. Finally, Gothard appears to have added a little “health and wealth” heresy to his teaching: follow these rules, and you will be blessed in every way.

Interestingly, Jinger remembers having an overall positive experience as she grew up in the Duggar household. Her parents did actually understand the Gospel and teach it to her, so she got that alongside Gothard’s harmful false teaching. However, Gothard’s false teaching seriously stunted her spiritual growth, causing her to live with an attitude that was simultaneously fearful and Pharisaical. It wasn’t until she met her future husband that she was exposed to better, more solid biblical teaching and was encouraged to study the Bible on her own, looking at what the passages were actually saying, not through the lens of Gothard. She left his false teaching in order to step in to a truer, richer understanding of the Gospel. I think it’s entirely appropriate that she share her story in a memoir that also examines Gothard’s false teachings. Through no choice of her own, as a Duggar she has been made a minor public figure and a representative of Christianity (not to be confused with Gothard’s teachings).

However, not everyone who grew up in a Gothard community was so fortunate. Gothard himself, who never married even though he gave lots of marriage and parenting advice (think that’s a red flag???), for years flirted with and sexually abused young women in his community. And Jinger’s older brother, Josh, became a sexual predator who ended up going to jail for possession of child pornography. As Paul points out about rules like Gothard’s, “Such regulations indeed have an appearance of wisdom, with their self-imposed worship, their false humility, and their harsh treatment of the body, but they lack any value in restraining sensual indulgence.” (Col. 2:23)

However, instead of seeing these sexual sins as an indictment of false teaching like Gothard’s, many people will see them as the natural outcome of Christianity. They will hold Jinger, as it were, responsible for these things unless she also rejects Christ. So, let’s look at the claims in my intro paragraph.

A long review, but with no spoilers! That’s how much is going on in this book!

This is about my third time to read this book. The first instance was many, many years ago, when I knew very little about life or about postwar England. At that time, the characters, their life circumstances, their personalities didn’t give me clues about the mystery, but rather were just another part of the exotic setting through which I stumbled, gaping and blinking.

I remember that I reread the book at least once in the interim, but I can’t remember the occasion. Probably I was so busy immersing myself to escape the stresses of everyday life that I didn’t absorb much except “how fun to read an Agatha Christie book.”

And then there’s this trip round. Third time’s the charm?

I bought this book in response to the news that Christie’s books are now going to be edited before they are published. New editions will remove language that could be hurtful, such as references to class, race, nationality, or people’s personal appearance. In other words, all the distinctive parts of the British world-view in the 30s through 60s that make the books interesting period pieces, that Christie often conveys subtly and sympathetically, and that often figure as important factors in the psychology of the murder mysteries. When I heard this news, my immediate thought was that I’d better build up my own library of older editions of Christie. Her whole corpus has always been widely and cheaply available in libraries and bookstores, but precisely because of this availability, it never occurred to me to build up a collection. I purchased A Murder Is Announced and then at once had occasion to lend it to a young person who had never heard about Christie, so that was my good deed for the month I guess. She finished it in a night or two, and when I got it back I of course re-read it.

It’s not hard to see, in this book, what parts would go on the sensitivity editor’s chopping-block.

Through the door surged a tempestuous young woman with a well-developed bosom heaving under a tight jersey. She had on a dirdl skirt of a bright colour and had greasy dark plaits wound round and round her head. Her eyes were dark and flashing.

She said gustily:

“I can speak to you, yes, please, no?”

Miss Blacklock sighed.

“Of course, Mitzi, what is it?”

ibid, p. 21

Sometimes she thought it would be preferable to do the entire work of the house as well as the cooking rather than be bothered with the eternal nerve storms of her refugee “lady help.”

Wow! Just look at that English stereotype of a foreigner. Mitzi wears bright colors, her hair is “greasy,” she is too curvy (body shaming!), and she is subject to “nerve storms.” Later in the story, we learn that Mitzi is dramatic, boastful, and “a liar.” What could be worse? Surely the sensitivity editor should get rid of this entire character. Unfortunately, Mitzi is rather important to the plot. She also embodies one of the themes in this book: the new conditions of life in the British countryside immediately after WWII.

“Helps to find out if people are who they say they are,” said Miss Marple.

She went on:

“Because that’s what’s worrying you, isn’t it? And that’s really the particular way the world has changed since the war. Take this place, Chipping Cleghorn, for instance. It’s very much like St. Mary Mead where I live. Fifteen years ago one knew who everybody was. … They were people whose fathers and mothers and grandfathers and grandmothers, or whose aunts and uncles, had lived there before them. If somebody new came to live there, they brought letters of introduction, or they’d been in the same regiment or served in the same ship as someone there already. If anybody new–really new–really a stranger–came, well, they stuck out–everybody wondered about them and didn’t rest till they found out.”

She nodded her head gently.

“But it’s not like that anymore. Every village and small country place is full of people who’ve just come and settled there without any ties to bring them. The big houses have been sold, and the cottages have been converted and changed. And people just come–and all you know about them is what they say of themselves. They’ve come, you see, from all over the world. People from India and Hong Kong and China, and people who used to live in France and Italy in cheap little places and odd islands. And people who’ve made a little money and can afford to retire. But nobody knows any more who anyone is. People take you at your own valuation. They don’t wait to call until they’ve had a letter from a friend saying that So-and-So’s are delightful people and she’s known them all their lives.”

And that, thought Craddock, was exactly what was oppressing him. He didn’t know. They were just faces and personalities and they were backed up by ration books and identity cards–nice neat identity cards with numbers on them, without photographs or fingerprints. Anybody who took the trouble could have a suitable identity card–and partly because of that, the subtler links that had held together English social rural life had fallen apart. In a town nobody expected to know his neighbor. In the country now nobody knew his neighbor either, though possibly he still thought he did …

ibid, pp. 126 – 127

The postwar conditions that Miss Marple is describing are pretty much what it’s like everywhere in America … at least, everywhere that I have lived. The idea that you might not visit someone, or get to know them, until you’ve had a letter of introduction from someone you do know, strikes an American as stifling. (In Indonesia, by the way, when you come to visit a new place you need a letter of introduction not from a mutual friend but from some kind of bureaucrat.)

Many of these “people” from overseas that Miss Marple describes would have been Englishmen and Englishwomen who had been living abroad before the war. One such person is Miss Blacklock, a main character in this mystery, who came to Chipping Cleghorn only two years ago. Her friend, Dora, and her niece and nephew, Julia and Patrick, who live with her, also came recently. But many others would have been not English but foreigners. Apparently, England had to digest a large influx of postwar refugees and this fact forms the background to many of Christie’s stories, this one in particular. Besides Mitzi, another character is a young Swiss man who works at a nearby hotel and who might not be entirely honest with money.

Christie is not entirely unsympathetic to foreigners. One of her sleuths, Hercule Poirot, is Belgian. English people tend not to take him seriously because he is a “dapper little man with an egg-shaped head” and a French accent, and this tendency to underestimate him often works in Poirot’s favor, just as the fact of her being an unprepossessing old maid works in Miss Marple’s. For example, here is a passage from another of Christie’s books:

Fortunately this queer little foreigner did not seem to know much English. Quite often he did not understand what you said to him, and when everyone was speaking more or less at once he seemed completely at sea. He appeared interested only in refugees and post war conditions, and his vocabulary only included those subjects. Ordinary chitchat appeared to bewilder him. More or less forgotten by all, Hercule Poirot leant back in his chair, sipped his coffee and observed, as a cat may observe, the twitterings, and comings and goings of a flock of birds. The cat is not yet ready to make its spring.

Funerals Are Fatal, pp. 167 – 168

In A Murder Is Announced, English characters make frequent references to the possibility that they themselves, or others, might be unjustly prejudiced against foreigners. And we get passages like this one:

“Please don’t be too prejudiced against the poor thing because she’s a liar. I do really believe that, like so many liars, there is a real substratum of truth behind her lies. I think that though, to take an instance, her atrocity stories have grown and grown until every kind of unpleasant story that has ever appeared in print has happened to her or her relations personally, she did have a bad shock initially and did see one, at least, of her relations killed. I think a lot of these displaced persons feel, perhaps justly, that their claim to our notice and sympathy lies in their atrocity value and so they exaggerate and invent.”

She added, “Quite frankly, Mitzi a maddening person. She exasperates and infuriates us all, she is suspicious and sulky, is perpetually having ‘feelings’ and thinking herself insulted. But in spite of it all, I really am sorry for her.” She smiled. “And also, when she wants to, she can cook very nicely.”

ibid, pp. 59 – 60

This is a really interesting speech. One the hand, it represents Miss Blacklock (and, presumably, Agatha Christie) trying to be fair to Mitzi. On the other hand, from my perspective it still doesn’t give Mitzi enough credit. Any European refugee from WWII was quite likely to have actually lost their entire family, and to have seen and suffered many real atrocities which would sound unbelievable if they were not documented. It was one of the most harrowing periods in modern history. Such people were likely to have severe PTSD which would, in fact, make them “suspicious” and jumpy. For example, when Mitzi is being interviewed by the police in the wake of the murder, she predicts that they will torture her and take her away to a concentration camp. There is no reason to think this is melodrama.

Other parts of Mitzi’s character, such as her boastfulness, emotionalism and tendency to get insulted, may be cultural differences that have nothing to do with the war. Nearly every culture is boastful and demonstrative compared to the Brits, and people tend to get insulted and sulky in shame-based cultures such as we find in Asia (and perhaps some parts of Eastern Europe).

Another aspect of postwar Britain is the increase in bureaucracy. Identity cards have already been mentioned–a sort of top-down attempt to keep track of people bureaucratically now that the older system of everybody knowing everybody has disintegrated–but there is also bureaucratic control of all aspects of the economy, even down to whether people barter:

Craddock said, “He was quite straightforward about being there, though. Not like Miss Hinchcliffe.”

Miss Marple coughed gently. “You must make allowances for the times we live in, Inspector,” she said.

Craddock looked at her, uncomprehendingly.

“After all,” said Miss Marple, “you are the Police, aren’t you? People can’t say everything they’d like to say to the Police, can they?”

“I don’t see why not,” said Craddock. “Unless they’ve got some criminal matter to conceal.”

“She means butter,” said Bunch. “Thursday is the day one of the farms round here makes butter. They let anybody they like have a bit. It’s usually Miss Hinchcliffe who collects it. But it’s all a bit hush hush, you know, a kind of local scheme of barter. One person gets butter, and sends along cucumbers, or something like that–and a little something when a pig’s killed. And now and then an animal has an accident and has to be destroyed. Oh, you know the sort of thing. Only one can’t, very well, say it right out to the Police. Because I suppose quite a lot of this barter is illegal–only nobody really knows because it’s all so complicated.”

ibid, pp. 214 – 215

I didn’t even notice this aspect of the book during the previous times I read it. This time, it jumped out at me, because somewhere I had seen an essay about how in the postwar years, England continued rationing as a sort of experiment in socialism and this kept people poor for longer than they otherwise would have been. C.S. Lewis, for example, like many in England, relied on care packages from friends in America for such things as ham. Having been sensitized to this aspect of it, on this go-round I realized how much this Christie book really is a time capsule.

And … “nobody really knows because it’s all so complicated” is truly the essence of bureaucracy!

But the Christie goodness doesn’t stop there. (Really, there is so much going on in this book!) There is the delightful Mrs. Goedler. She is actually a very minor character … the widow of Miss Blacklock’s financier employer. Miss Blacklock stands to inherit if Mrs. Goedler predeceases her, which is very likely to happen because Mrs. Goedler has had poor health for years and is now likely to die within a few weeks. Inspector Craddock visits her, and Mrs. Goedler has this to say:

“Why, exactly, did your husband leave his money the way he did?”

“You mean, why did he leave it to Blackie? Not for the reason you’ve probably been thinking.” Her roguish twinkle was very apparent. “What minds you policemen have! Randall was never in the least in love with her and she wasn’t with him. Letitia, you know, has really got a man’s mind. She hasn’t any feminine feelings or weaknesses. I don’t believe she was ever in love with any man. She was never particularly pretty and she didn’t care for clothes. She used a little makeup in deference to prevailing custom, but not to make herself look prettier.” There was pity in the old voice as she went on: “She never knew any of the fun of being a woman.”

Craddock looked at the frail little figure in the big bed with interest. Belle Goedler, he realized, had enjoyed–still enjoyed–being a woman. She twinkled at him.

“I’ve always thought,” she said, “it must be terribly dull to be a man.”

ibid, p. 169

Now, that’s awfully inspiring to a gal like me. But Belle Goedler is not finished giving us advice on how to live:

She nodded her head at him.

“I know what you’re thinking. But I’ve had all the things that make life worth while–they may have been taken from me–but I have had them. I was pretty and gay as a girl, I married the man I loved, and he never stopped loving me … My child died, but I had him for two precious years … I’ve had a lot of physical pain–but if you have pain, you know how to enjoy the exquisite pleasure of the times when pain stops. And everyone’s been kind to me, always … I’m a lucky woman, really.”

ibid, p. 171

Go and do likewise.

Three book and two movie reviews:

by Pete Hegseth with David Goodwin, 2022

I don’t usually go for books with an American flag on the cover. Fairly or unfairly, I expect them to have been written in six weeks with a shallow diagnosis of the problem (and the solution usually being “free-market economics”). But this one is different. The author began to win my trust when he said that a few of his earlier books were, in fact, just like that. Also, the intro is by David Goodwin, who has been in Christian classical education for years.

It’s pretty depressing to read how what Hegseth calls the Western Christian Paideia (WCP) was ripped out of American schools a few years before my parents were born (and how, in fact, the public school system was set up primarily to do this). It was replaced by a shallow new religion, a blend of Hegelianism with some nationalism thrown in to make it palatable to my grandparents’ generation. The goal of this new paideia was to populate a brave new, progressive, technocratic world with obedient and easily manipulated citizens, not with educated, critically-thinking grown adults. So, that kid on the cover looking at the American flag in a pose that looks suspiciously like worship? That’s not what the author is promoting. It’s what he’s criticizing.

by Larry Chambers and Dale Rogers, 2004 (3rd ed.)

Investors don’t get much more first-time than yours truly.

The big insight from this book – if I can summarize what I’ve read so far – is that it’s not possible to “pick stocks.” Stocks go up and down in a truly random way. (Which is gratifying to hear, since that’s certainly how it looks from the outside!) So, say the authors, the way to make money long-term on the stock market is to pick the right balance of kinds of stocks. And the kind that do the best, on average, are the companies that appear the least promising.

There. You got that for free.

by Jean Hanff Korelitz, 2021

Here’s my Goodreads review:

Hoo boy. Hokay. So.

This book is about a struggling author who “steals” a story that someone once told him, years later, after he finds out the person is deceased. Said story is so sensational that it catapults the author to success: the book becomes a phenomenon. The rise and fall of this author is the outer onion layer of this book.

The inner onion layer is the sensational story itself. It’s about a girl who, at fifteen, becomes pregnant by a random guy, an older married man to whom she intentionally loses her virginity, essentially as a big middle finger to her parents. Her parents force her, not only to carry the baby to term (horror of horrors!), but to raise it in their home. When the baby, which turns out to be a precocious girl, is sixteen and ready to go off to college, the mother kills her. This is the Big Twist that shocks readers and is responsible for the book’s success.

I have three thoughts. One, obviously this book is really well written and makes a compelling read. I finished it in four days, despite my busy life. Hence the four stars.

Two. Every single main character is this book is a sociopath. I include not only the mother, but the daughter (as far as we can tell), the struggling-to-famous author, and a couple of side characters as well. The mother is a smart sociopath with the courage of her convictions, and the author is a dumber, more cowardly sociopath. There isn’t a character we get to know well who is manifestly decent.

Three. Despite being a book about a mother who kills her teenaged daughter, this book somehow manages to be pro-abortion. The fictional pregnant teen is resentful that her parents won’t take her to go get an abortion. They don’t love her or the baby, she opines, they are making her raise it to punish her. Abortion is presented as a solution, as if it would have prevented this very tragedy rather than just anticipating it by sixteen years. The parents also, though “Christian,” forbid their daughter to adopt the baby out, again to punish her. This is the classic straw-man scenario used by abortion promoters, but I don’t think it’s actually very common, let alone widespread. The impression I get is that grandparents often end up raising their daughters’ out-of-wedlock children. Furthermore, Korelitz clearly has no love for pro-life counseling clinics, which are actually places that will give girls in crisis pregnancies assistance in adoption and will give them plenty of other kinds of support when those are lacking at home. These places, when mentioned in the book, are always called abortion “counselors,” with scare quotes, as if the fact they will encourage you not to have your baby killed makes them somehow less professional.

This abortion problem, plus certain things in the tone of the book, gave me the distinct impression that Korelitz is trying to make this kind of sociopathy relatable. For example, one character asserts that it’s sexist of the reading public to find it more shocking when a mother kills her child than when a father does the same. Truly, women’s lib has reached its zenith when women aren’t expected to have any motherly tenderness for their own children, but rather to be just as violent and sociopathic as men are “allowed” to be. And then we can all be good worshippers of Moloch. Yay? It is for this reason that I can’t give the book five stars. No matter how well plotted or rendered, my enjoyment of a story as a story is marred when I find its background assumptions this repellant.

I know this is not a new movie, but I’d never seen it before. All I can say is, Tyler Perry really “gets” women. (Far more than Jean Hanff Korelitz does, now that I think of it.)

I did expect Madea to bring more action/solutions and not just comic relief, but interestingly, in this movie the solutions come from … God. I’m fine with that. Now before you go thinking that the frequent references to God mean this movie has an unrealistically rosy outlook on human nature … it’s also a revenge fantasy. Also, it’s got the usual Tyler Perry crude jokes, including Perry playing, not just cousin Brian and Madea, but also Madea’s pervy octogenarian brother.

This film is very violent, very shooty-shooty-bang-bang. If you can tolerate that, it’s a great movie. It starts out looking like a crime/thriller flick. I didn’t realize until about 3/4 of the way through that it’s actually an updated Western. There is a noontime shootout on Main Street and everything, except instead of just the sheriff on one side and the outlaw on the other, there’s about a dozen people on each side.

There’s also a bonnet-wearing Texas granny who pulls a shotgun out of her knitting basket, which as you can imagine, I loved.

So, I finally read Nora Ephron’s iconic (?) I Feel Bad About My Neck. I bought it because it was on sale at the library table for $1 and, when I started browsing through, it did not fail to charm me.

IFBAMN came out, according to the cover flap, in 2006. At that time, I had been married for about five minutes and had no interest in crepey necks. Now, the topic is of mild interest because I am older and wiser. (So old! So wise!) It’s fitting that I picked up this book during the week before my birthday. Perhaps we can call this my I-am-within-sight-of-turning-50 post.

Ephron and I do not have a lot in common. Unlike me, she …

All of this puts our worlds pretty far apart.

(However, I would be remiss if I did not point out that Nora Ephron and I also have quite a few things in common:

Anyway, all that to say, even with our experiences being so far apart, I find this book of collected essays enjoyable and funny. I can only imagine how hilarious it must be to Ephron’s fellow New Yorkers.

And no, it is not all about necks. That is only the first essay. I am really glad, because there is no way anyone could sustain an entire book about their neck. The second essay, for example, is about how every time Ephron tries to get a new purse, the interior of it instantly becomes a disorganized Bermuda Triangle of Tictacs and Kleenexes and things, and it was this essay that really won my heart and convinced me that this New Yorker and I are kindred spirits.

Three stars.

I picked this up with moderately high hopes. The protagonists are all sixty-year-old ladies who spent their youth as private assassins. I thought there would be more old-lady thoughts, but in the end, they mostly seem like 21-year-olds in 60-year-old bodies. So, the character development and themes disappointed a bit.

What did not disappoint was the research and the plot. Unlike some novels, where the premise is only half-developed, this one takes us on a very thorough ride. We get to see how the ladies got recruited, how they got trained, and to see a number of hits they did in their youth, in exotic locations throughout the world. These interleave with hits they are carrying out now, in their old age, in self-defense. There is not just one but many tense, intricate, detailed climatic action scenes. And it all works together into one big, overarching tale of betrayal. It’s like not just one, but all of the Mission: Impossible movies, in novel form. If this had billed itself just as a thriller, then these factors alone would cause me to give it four or five stars.

But unfortunately, the cover and premise promised not just Thriller, but a study of what it’s like to be a woman of a certain age. Have your goals changed? Do you miss what you were able to do in your youth, or are you content with that and ready to move on to something else? Have you left a legacy? Had any children? Are you ready to go?

No, none of that. One of the four women has married, but the only effect of her recent widowhood is to make her lose her nerve in survival situations. Another has married another woman; another is still chasing younger men at sixty. Meanwhile, the main character, Billie, never married or had children.

He was six years older than me and ready to settle down, build a life, make some babies. And no matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t figure out how to make myself small enough to fit into that picture.

page 309

So, Billie, you think making and raising people is a small life, huh? It is sooo much smaller than your life of traveling around the world killing people. You couldn’t reduce yourself to being a mom.

This quote pretty much encapsulates the book’s shallow yet heavy-handed feminism, and it is the reason I have bumped it down to three stars.

| My age | Profession | Clarification |

| early 20s | Moron | I still practice this profession on & off to this day. |

| late 20s to early 30s | Missionary | Least said, soonest mended. |

| 31 onwards | Mom | Another one that I haven’t given up. |

| early 40s | Mmmnovelist | Anything for alliteration. |

| late 40s | Magistra | i.e., Latin teacher |

| old age (planned) | Morticia Adams | (A long-haired witchy-looking older woman that you don’t mess with) |

What’s YOUR five-decade plan?